Fayum mummy portraits

Mummy portraits or Fayum mummy portraits are a type of naturalistic painted portrait on wooden boards attached to upper class mummies from Roman Egypt. They belong to the tradition of panel painting, one of the most highly regarded forms of art in the Classical world. The Fayum portraits are the only large body of art from that tradition to have survived. They were formerly, and incorrectly, called Coptic portraits.

Mummy portraits have been found across Egypt, but are most common in the Faiyum Basin, particularly from Hawara and the Hadrianic Roman city Antinoopolis. "Faiyum portraits" is generally used as a stylistic, rather than a geographic, description. While painted cartonnage mummy cases date back to pharaonic times, the Faiyum mummy portraits were an innovation dating to the time of Roman rule in Egypt.[1] The portraits date to the Imperial Roman era, from the late 1st century BC or the early 1st century AD onwards. It is not clear when their production ended, but some research suggests the middle of the 3rd century. They are among the largest groups among the very few survivors of the panel painting tradition of the classical world, which continued into Byzantine, Eastern Mediterranean, and Western traditions in the post-classical world, including the local tradition of Coptic Christian iconography in Egypt.

The portraits covered the faces of bodies that were mummified for burial. Extant examples indicate that they were mounted into the bands of cloth that were used to wrap the bodies. Almost all have now been detached from the mummies.[2] They usually depict a single person, showing the head, or head and upper chest, viewed frontally. In terms of artistic tradition, the images clearly derive more from Greco-Roman artistic traditions than Egyptian ones.[3] Two groups of portraits can be distinguished by technique: one of encaustic (wax) paintings, the other in tempera. The former are usually of higher quality.

About 900 mummy portraits are known at present.[4] The majority were found in the necropolis of Faiyum. Due to the hot dry Egyptian climate, the paintings are frequently very well preserved, often retaining their brilliant colours seemingly unfaded by time.

History of research

[edit]Pre-19th century

[edit]

The Italian explorer Pietro Della Valle, on a visit to Saqqara-Memphis in 1615, was the first European to discover and describe mummy portraits. He transported some mummies with portraits to Europe, which are now in the Albertinum (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden).[5]

19th-century collectors

[edit]Although interest in ancient Egypt steadily increased after that period, further finds of mummy portraits did not become known before the early 19th century. The provenance of these first new finds is unclear; they may come from Saqqara as well, or perhaps from Thebes. In 1820, the Baron of Minotuli acquired several mummy portraits for a German collector, but they became part of a whole shipload of Egyptian artifacts lost in the North Sea. In 1827, Léon de Laborde brought two portraits, supposedly found in Memphis, to Europe, one of which can today be seen at the Louvre, the other in the British Museum. Ippolito Rosellini, a member of Jean-François Champollion's 1828–29 expedition to Egypt, brought a further portrait back to Florence. It is so similar to de Laborde's specimens that it is thought to be from the same source.[5] During the 1820s, the British Consul General to Egypt, Henry Salt, sent several further portraits to Paris and London. Some of them were long considered portraits of the family of the Theban Archon Pollios Soter, a historical character known from written sources, but this has turned out to be incorrect.[5]

Once again, a long period elapsed before more mummy portraits came to light. In 1887, Daniel Marie Fouquet heard of the discovery of numerous portrait mummies in a cave. He set off to inspect them some days later, but arrived too late, as the finders had used the painted plaques for firewood during the three previous cold desert nights. Fouquet acquired the remaining two of what had originally been fifty portraits. While the exact location of this find is unclear, the likely source is from er-Rubayat.[5] At that location, not long after Fouquet's visit, the Viennese art trader Theodor Graf found several further images, which he tried to sell as profitably as possible. He engaged the famous Egyptologist Georg Ebers to publish his finds. He produced presentation folders to advertise his individual finds throughout Europe. Although little was known about their archaeological find contexts, Graf went as far as to ascribe the portraits to known Ptolemaic pharaohs by analogy with other works of art, mainly coin portraits. None of these associations were particularly well argued or convincing, but they gained him much attention, not least because he gained the support of well-known scholars like Rudolf Virchow. As a result, mummy portraits became the centre of much attention.[6] By the late 19th century, their very specific aesthetic made them sought-after collection pieces, distributed by the global arts trade.

Archaeological study: Flinders Petrie

[edit]

In parallel, more scientific engagement with the portraits was beginning. In 1887, the British archaeologist Flinders Petrie started excavations at Hawara. He discovered a Roman necropolis which yielded 81 portrait mummies in the first year of excavation. At an exhibition in London, these portraits drew large crowds. In the following year, Petrie continued excavations at the same location but now suffered from the competition of a German and an Egyptian art dealer. Petrie returned in the winter of 1910–11 and excavated a further 70 portrait mummies, some of them quite badly preserved.[7] With very few exceptions, Petrie's studies still provide the only examples of mummy portraits so far found as the result of systematic excavation and published properly. Although the published studies are not entirely up to modern standards, they remain the most important source for the find contexts of portrait mummies.

Late-19th- and early-20th-century collectors

[edit]In 1892, the German archaeologist von Kaufmann discovered the so-called "Tomb of Aline", which held three mummy portraits; among the most famous today. Other important sources of such finds are at Antinoöpolis and Akhmim. The French archaeologist Albert Gayet worked at Antinoöpolis and found much relevant material, but his work, like that of many of his contemporaries, does not satisfy modern standards. His documentation is incomplete, many of his finds remain without context.

Museums

[edit]Today, mummy portraits are represented in all important archaeological museums of the world. Many have fine examples on display, notably the British Museum, the National Museum of Scotland, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Louvre in Paris.[8] Because they were mostly recovered through inappropriate and unprofessional means, virtually all are without archaeological context, a fact which consistently lowers the quality of archaeological and culture-historical information they provide. As a result, their overall significance as well as their specific interpretations remain controversial.[8]

Materials and techniques

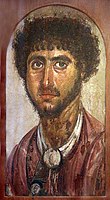

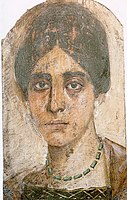

[edit]A majority of images show a formal portrait of a single figure, facing and looking toward the viewer, from an angle that is usually slightly turned from full face. The figures are presented as busts against a monochrome background which in some instances are decorated. The individuals are both male and female and range in age from childhood to old age.

Painted surface

[edit]-

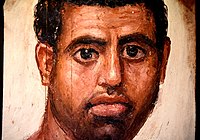

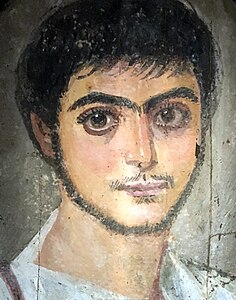

Mummy portrait of a man from Fayum. Encaustic on limewood, AD 80–100. British Museum

-

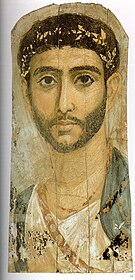

Mummy portrait of a woman from Fayum, Hawara, modern-day Egypt. Encaustic on wood, AD 300–325. British Museum

The majority of preserved mummy portraits were painted on boards or panels, made from different imported hardwoods, including oak, lime, sycamore, cedar, cypress, fig, and citrus.[9] The wood was cut into thin rectangular panels and made smooth. The finished panels were set into layers of wrapping that enclosed the body and were surrounded by bands of cloth, giving the effect of a window-like opening through which the face of the deceased could be seen. Portraits were sometimes painted directly onto the canvas or rags of the mummy wrapping (cartonnage painting).

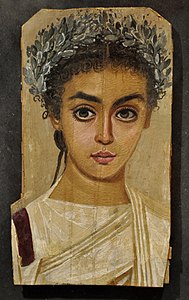

Painting techniques

[edit]The wooden surface was sometimes primed for painting with a layer of plaster. In some cases the primed layer reveals a preparatory drawing. Two painting techniques were employed: encaustic (wax) painting and animal glue tempera. The encaustic images are striking because of the contrast between vivid and rich colours, and comparatively large brush-strokes, producing an "Impressionistic" effect. The tempera paintings have a finer gradation of tones and chalkier colours, giving a more restrained appearance.[8] In some cases, gold leaf was used to depict jewellery and wreaths. There also are examples of hybrid techniques or of variations from the main techniques.

The Fayum portraits reveal a wide range of painterly expertise and skill in presenting a lifelike appearance. The naturalism of the portraits is often revealed in knowledge of anatomic structure and in skilled modelling of the form by the use of light and shade, which gives an appearance of three-dimensionality to most of the figures. The graded flesh tones are enhanced with shadows and highlights indicative of directional lighting.

Subjects and social context of the paintings

[edit]-

Portrait of a boy, identified by inscription as Eutyches (Greek: Ευτύχης), Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

A portrait from the late 1st century AD. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

-

Man with sword belt, Altes Museum.

People of Fayum

[edit]Under Hellenic rule, Egypt hosted several Greek settlements, mostly concentrated in Alexandria, but also in a few other cities, where Greek settlers lived alongside some seven to ten million native Egyptians,[10] or possibly a total of three to five million for all ethnicities, according to lower estimates.[11] Faiyum's earliest Greek inhabitants were soldier-veterans and cleruchs (elite military officials) who were settled by the Ptolemaic kings on reclaimed lands.[10][12] Native Egyptians also came to settle in Faiyum from all over the country, notably the Nile Delta, Upper Egypt, Oxyrhynchus and Memphis, to undertake the labor involved in the land reclamation process, as attested by personal names, local cults and recovered papyri.[13] It is estimated that as much as 30 percent of the population of Faiyum was Greek during the Ptolemaic period, with the rest being native Egyptians.[13] By the Roman period, much of the "Greek" population of Faiyum was made-up of either Hellenized Egyptians or people of mixed Egyptian-Greek origins.[14] Later, in the Roman Period, many veterans of the Roman army, who, initially at least, were not Egyptian but people from disparate cultural and ethnic backgrounds, settled in the area after the completion of their service, and formed social relations and intermarried with local populations.[15]

While commonly believed to depict Greek settlers in Egypt,[16] the Faiyum portraits instead reflect the complex synthesis of the predominant Egyptian culture and that of the elite Greek minority in the city. According to Walker, the early Ptolemaic Greek colonists married local women and adopted Egyptian religious beliefs, and by Roman times, their descendants were viewed as Egyptians by the Roman rulers, despite their own self-perception of being Greek.[13]

The portraits are said to represent both descendants of ancient Greek mercenaries, who had fought for Alexander the Great, settled in Egypt and married local women,[13] as well as native Egyptians who were the majority, many of whom had adopted Greek or Latin names, then seen as 'status symbols'.[17][18][19][20]

A DNA study showed genetic continuity between the Pre-Ptolemaic, Ptolemaic and Roman populations of Egypt, indicating that foreign rule impacted Egypt's population only to a very limited degree at the genetic level.[21]

In terms of anthropological characteristics, academic Alan K. Bowman stated that based on skull analysis, the Faiyum mummy burials were said to be the same as 'native' Egyptians of the Pharaonic era.[22] The dental morphology[23] of the Roman-period Faiyum mummies was also compared with that of earlier Egyptian populations, and was found to be "much more closely akin" to that of ancient Egyptians, than to Greeks or other European populations.[24] This conclusion was seen again in 2009, by Joel D. Irish, where he noted: "Interestingly, Roman period Hawara in Lower Egypt seems not to have been composed of migrants-while there is a possibility that the dynastic occupation of Saqqara may have been."[25]

Age profile of those depicted

[edit]Most of the portraits depict the deceased at a relatively young age, and many show children. According to Susan Walker, C.A.T. scans reveal a correspondence of age and sex between mummy and image. She concludes that the age distribution reflects the low life expectancy at the time. It was often believed that the wax portraits were completed during the life of the individual and displayed in their home, a custom that belonged to the traditions of Greek art,[26] but this view is no longer widely held given the evidence suggested by the C.A.T. scans of the Faiyum mummies, as well as Roman census returns. In addition, some portraits were painted directly onto the coffin; for example, on a shroud or another part.

Social status

[edit]The patrons of the portraits apparently belonged to the affluent upper class of military personnel, civil servants and religious dignitaries. Not everyone could afford a mummy portrait; many mummies were found without one. Flinders Petrie states that only one or two percent of the mummies he excavated were embellished with portraits.[27] The rates for mummy portraits do not survive, but it can be assumed that the material caused higher costs than the labour, since in antiquity, painters were appreciated as craftsmen rather than as artists.[27] The situation from the "Tomb of Aline" is interesting in this regard. It contained four mummies: those of Aline, of two children and of her husband. Unlike his wife and children, the latter was not equipped with a portrait but with a gilt three-dimensional mask. Perhaps plaster masks were preferred if they could be afforded.

Based on literary, archaeological and genetic studies, it appears that those depicted were native Egyptians, who had adopted the dominant Greco-Roman culture.[21]

Hairstyles and clothing are always influenced by Roman fashion. Women and children are often depicted wearing valuable ornaments and fine garments, men often wearing specific and elaborate outfits. Men with beards were seen as having masculinity, maturity, and high social status. They were seen to have wisdom.[28] Greek inscriptions of names are relatively common, sometimes they include professions. It is not known whether such inscriptions always reflect reality, or whether they may state ideal conditions or aspirations rather than true conditions.[29] One single inscription is known to definitely indicate the deceased's profession (a shipowner) correctly. The mummy of a woman named Hermione also included the term γραμματική (grammatike). For a long time, it was assumed that this indicated that she was a teacher by profession; for this reason, Flinders Petrie donated the portrait to Girton College, Cambridge, the first residential college for women in Britain. However, today, it is assumed that the term indicates her level of education. Some portraits of men show sword-belts or even pommels, suggesting that they were members of the Roman military.[30]

Culture-historical context

[edit]Changes in burial habits

[edit]The burial habits of Ptolemaic Egyptians mostly followed ancient traditions. The bodies of members of the upper classes were mummified, equipped with a decorated coffin and a mummy mask to cover the head. The Greeks who entered Egypt at that time mostly followed their own habits. There is evidence from Alexandria and other sites indicating that they practised the Greek tradition of cremation. This broadly reflects the general situation in Hellenistic Egypt, its rulers proclaiming themselves to be pharaohs but otherwise living in an entirely Hellenistic world, incorporating only very few local elements. Conversely, the Egyptians only slowly developed an interest in the Greek-Hellenic culture that dominated the East Mediterranean since the conquests of Alexander. This situation changed substantially with the arrival of the Romans. Within a few generations, all Egyptian elements disappeared from everyday life. Cities like Karanis or Oxyrhynchus are largely Greco-Roman places. There is clear evidence that this resulted from a mixing of different ethnicities in the ruling classes of Roman Egypt.[31][32]

Religious continuity

[edit]Only in the sphere of religion is there evidence for a continuation of Egyptian traditions. Egyptian temples were erected as late as the 2nd century. In terms of burial habits, Egyptian and Hellenistic elements now mixed. Coffins became increasingly unpopular and went entirely out of use by the 2nd century. In contrast, mummification appears to have been practised by large parts of the population. The mummy mask, originally an Egyptian concept, grew more and more Graeco-Roman in style, Egyptian motifs became ever rarer. The adoption of Roman portrait painting into Egyptian burial cult belongs in this general context.[33]

Link with Roman funeral masks

[edit]Some authors suggest that the idea of such portraits may be related to the custom among the Roman nobility of displaying imagines, images of their ancestors, in the atrium of their house. In funeral processions, these wax masks were worn by professional mourners to emphasize the continuity of an illustrious family line, but originally perhaps to represent a deeper evocation of the presence of the dead. Roman festivals such as the Parentalia as well as everyday domestic rituals cultivated ancestral spirits (see also veneration of the dead). The development of mummy portraiture may represent a combination of Egyptian and Roman funerary practices, since it appears only after Egypt was established as a Roman province.[34]

Salon paintings

[edit]The images depict the heads or busts of men, women and children. They probably date from c. 30 BC to the 3rd century.[35] To the modern eye, the portraits appear highly individualistic. Therefore, it has been assumed for a long time that they were produced during the lifetime of their subjects and displayed as "salon paintings" within their houses, to be added to their mummy wrapping after their death. Newer research rather suggests that they were only painted after death,[8] an idea perhaps contradicted by the multiple paintings on some specimens and the (suggested) change of specific details on others. The individualism of those depicted was actually created by variations in some specific details, within a largely unvaried general scheme.[8] The habit of depicting the deceased was not a new one, but the painted images gradually replaced the earlier Egyptian masks, although the latter continued in use for some time, often occurring directly adjacent to portrait mummies, sometimes even in the same graves.

-

Fayum mummy portrait of a man, 1st century AD, Oriental Institute, Chicago

-

Fayum portrait of a man, mid-2nd century, Myers Collection, Eton College.

-

Fayum portrait of a woman, 4th century, Museo archeologico nazionale, Florence

-

Fayum portrait of a woman, 2nd century, Manchester Museum, University of Manchester

Style

[edit]The combination of naturalistic Greek portrait of the deceased with Egyptian-form deities, symbols, and frame was primarily phenomenon of funerary art from the chora, or countryside, in Roman Egypt. Combining Egyptian and Greek pictorial forms or motifs was not restricted to funerary art, however: the public and highly visible portraits of Ptolemaic dynasts and Roman emperors grafted iconography developed for a ruler's Greek or Roman images onto Egyptian statues in the dress and posture of Egyptian kings and queens. The possible combinations of Greek and Egyptian elements can be elucidated by imposing a (somewhat artificial) distinction between form and content, where 'form' is taken as the system of representation, and 'content' as the symbol, concept, or figure being portrayed.[36]

Coexistence with other burial habits

[edit]The religious meaning of mummy portraits has not, so far, been fully explained, nor have associated grave rites. There is some indication that it developed from genuine Egyptian funerary rites, adapted by a multi-cultural ruling class.[8] The tradition of mummy portraits occurred from the Delta to Nubia, but it is striking that other funerary habits prevailed over portrait mummies at all sites except those in the Faiyum (and there especially Hawara and Achmim) and Antinoopolis. In most sites, different forms of burial coexisted. The choice of grave type may have been determined to a large extent by the financial means and status of the deceased, modified by local customs. Portrait mummies have been found both in rock-cut tombs and in freestanding built grave complexes, but also in shallow pits. It is striking that they are virtually never accompanied by any grave offerings, with the exception of occasional pots or sprays of flowers.[37]

End of the mummy portrait tradition

[edit]-

Fayum mummy portrait of a man named Herakleides, 50–100 AD, Getty Villa

-

Portrait of a woman named Isidora from Ankyronpolis, 100–110 AD, Getty Villa

-

Fayum portrait of a woman from Hawara, 75–100 AD, Getty Villa

For a long time, it was assumed that the latest portraits belong to the end of the 4th century, but recent research has modified this view considerably, suggesting that the last wooden portraits belong to the middle, the last directly painted mummy wrappings to the second half of the 3rd century. It is commonly accepted that production reduced considerably since the beginning of the 3rd century. Several reasons for the decline of the mummy portrait have been suggested; no single reason should probably be isolated, rather, they should be seen as operating together.

- In the 3rd century the Roman Empire underwent a severe economic crisis, severely limiting the financial abilities of the upper classes. Although they continued to lavishly spend money on representation, they favoured public appearances, like games and festivals, over the production of portraits. However, other elements of sepulchral representation, like sarcophagi, did continue.

- There is evidence of a religious crisis at the same time. This may not be as closely connected with the rise of Christianity as previously assumed. (The earlier suggestion of a 4th-century end to the portraits would coincide with the widespread distribution of Christianity in Egypt. Christianity also never banned mummification.) An increasing neglect of Egyptian temples is noticeable during the Roman imperial period, leading to a general drop in interest in all ancient religions.

- The Constitutio Antoniniana, i.e. the granting of Roman citizenship to all free subjects changed the social structures of Egypt. For the first time, the individual cities gained a degree of self-administration. At the same time, the provincial upper classes changed in terms of both composition and inter-relations.

Thus, a combination of several factors appears to have led to changes of fashion and ritual. No clear causality can be asserted.[38]

Considering the limited nature of the current understanding of portrait mummies, it remains distinctly possible that future research will considerably modify the image presented here. For example, some scholars suspect that the centre of production of such finds, and thus the centre of the distinctive funerary tradition they represent, may have been located at Alexandria. New finds from Marina el-Alamein strongly support such a view.[6] In view of the near-total loss of Greek and Roman paintings, mummy portraits are today considered to be among the very rare examples of ancient art that can be seen to reflect "Great paintings" and especially Roman portrait painting.[8]

Mummy portraits as sources on provincial Roman fashion

[edit]Provincial fashions

[edit]Mummy portraits depict a variety of different Roman hairstyles. They are one of the main aids in dating the paintings. The majority of the deceased were depicted with hairstyles then in fashion. They are frequently similar to those depicted in sculpture.[citation needed] As part of Roman propaganda, such sculptures, especially those depicting the imperial family, were often displayed throughout the empire. Thus, they had a direct influence on the development of fashion. Nevertheless, the mummy portraits, as well as other finds, suggest that fashions lasted longer in the provinces than in the imperial court, or at least that diverse styles might coexist.[citation needed]

Hairstyles

[edit]-

Depiction of a woman with curly hair, wearing a violet chiton and cloak and pendant earrings. British Museum

-

The plaited hairstyle of this elite woman makes it possible to date this painting to the reign of Trajan (98–117). Walters Art Museum

-

Depiction of a woman with a ringlet hairstyle, an orange chiton with black bands and rod-shaped earrings. Museum of Scotland

Comparing the hairstyles on mummy portraits, it is revealed that the vast majority of them correspond to the fast-changing fashion of hairstyles used by the elite of the rest of the Roman Empire. They, in turn, often followed the fashion of the Roman emperors and their wives, whose images and coiffures can be dated through their depictions on coins.[citation needed] The female hairstyles are what is usually used for the dating of mummy portraits, because other than a number of elite boys who had long hair parted on the forehead and bound into a bun in the neck, male hairstyle does not differ by much. This is because Roman male was advised to avoid excessive attention to hairstyles as he may be criticized for unmanliness. Complex ringlets with nested plaits, and curls over the forehead was popular in the late first century, with small oval nested plaits popular in the time of Antonines. A later popular woman's hairstyle is one inspired by the Roman Empress, Faustina I, with longer strands at the middle of the scalp drawn back into twists or plaits that were then wound into a tutulus at the crown of the head. Central-parted hair-knots at the back of the neck were common later in the same period. Empress Julia Domna popularized fluffy waved hair. Straight hair was common in the same period while later plaits on the crown of the head were rarely present.[citation needed]

Clothing

[edit]Other than representations of their wealth and social status, the subject's clothing suggests their previous roles in their local communities. For instance, men depicted to show their bare upper torso were usually athletes. The most common attire is a cloak worn over a chiton.[citation needed] It is common to have a traditionally Roman decorative line, clavus (plural clavi), on the subject's clothing. Most of the decorative lines are dark colored. While painted mummy portraits are shown to bear the traditional Roman decorative lines, not a single portrait has been definitely shown to depict the toga. It should, however, be kept in mind that Greek cloaks and togas are draped very similarly on depictions of the 1st and early 2nd centuries. In the late 2nd and 3rd centuries, togas should be distinguishable, but fail to occur.[citation needed]

Jewelry

[edit]Apart from the gold wreaths worn by many men, with very few exceptions, only women are depicted with jewellery. This generally accords with the common jewellery types of the Graeco-Roman East. Especially the Antinoopolis portraits depict simple gold link chains and massive gold rings. There are also depictions of precious or semi-precious stones like emerald, carnelian, garnet, agate or amethyst, rarely also of pearls. The stones were normally ground into cylindrical or spherical beads. Some portraits depict elaborate colliers, with precious stones set in gold.[citation needed]

The gold wreath was apparently rarely, if ever, worn in life, but a number have been found in graves from much earlier periods. Based on the plant wreaths given as prizes in contests, the idea was apparently to celebrate the achievements of the deceased in life.

There are three basic shapes of ear ornaments: Especially common in the 1st century are circular or drop-shaped pendants. Archaeological finds indicate that these were fully or semi-spherical. Later tastes favoured S-shaped hooks of gold wire, on which up to five beads of different colours and materials could be strung. The third shape are elaborate pendants with a horizontal bar from which two or three, occasionally four, vertical rods are suspended, usually each decorated with a white bead or pearl at the bottom. Other common ornaments include gold hairpins, often decorated with pearls, fine diadems, and, especially at Antinoopolis, gold hairnets. Many portraits also depict amulets and pendants, perhaps with magical functions.[39]

Art-historical significance

[edit]

The mummy portraits have immense art-historical importance. Ancient sources indicate that panel painting rather than wall painting (i.e., painting on wood or other mobile surfaces) was held in high regard, but very few ancient panel paintings survive. One of the few examples besides the mummy portraits is the Severan Tondo, also from Egypt (around 200), which, like the mummy portraits, is believed to represent a provincial version of contemporary style.[43]

Some aspects of the mummy portraits, especially their frontal perspective and their concentration on key facial features, strongly resemble later icon painting. A direct link has been suggested, but it should be kept in mind that the mummy portraits represent only a small part of a much wider Graeco-Roman tradition, the whole of which later bore an influence on the art of late antiquity and Byzantine art. A pair of panel "icons" of Serapis and Isis of comparable date (3rd century) and style are in the Getty Museum at Malibu;[44] as with the cult of Mithras, earlier examples of cult images were sculptures or pottery figurines, but from the 3rd century reliefs and then painted images are found.[45]

Gallery

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]The Fayum mummy images were used to recreate Jewish faces from first-century Judaea for the 2021 Israeli film Legend of Destruction.[46]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Berman, Lawrence; Freed, Rita E.; and Doxey, Denise. Arts of Ancient Egypt. p. 193. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. 2003. ISBN 0-87846-661-4

- ^ Examples still attached are in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo and the British Museum

- ^ Oakes, Lorna; Gahlin, Lucia. Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Reference to the Myths, Religions, Pyramids and Temples of the Land of the Pharaohs. p. 236 Hermes House. 2002. ISBN 1-84477-008-7

- ^ Corpus of all known specimens: Klaus Parlasca (1969–2003). Ritratti di mummie. Repertorio d'arte dell'Egitto greco-romano Serie B, v. 1-4. Rome.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)A further specimen discovered since: B. T. Trope; S. Quirke; P. Lacovara (2005). Excavating Egypt: great discoveries from the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College, London. Atlanta, Georgia: Michael C. Carlos Museum. p. 101. ISBN 1-928917-06-2.

- ^ a b c d Borg (1998), p. 10f.

- ^ a b Borg (1998), pp. 13f., 34ff.

- ^ Petrie (1911), p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicola Hoesch (2000). "Mumienporträts". Der Neue Pauly. Vol. 8. p. 464.

- ^ Wrede (1982), p. 218.

- ^ a b Adams, Winthrope L. (2006). "The Hellenistic Kingdoms". In Bugh, Glenn Richard (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Hellenistic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-521-53570-0.

The rest of Egypt was kept divided into the forty-two districts (called hsaput in Egyptian and nomos in Greek), which had been traditional for over 3,000 years. Here, some seven to ten million native Egyptians lived the same life they had always led.

- ^ Rathbone, D. W. (1990). "Villages, Land and Population in Graeco-Roman Egypt". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society. 36 (216): 103–142. doi:10.1017/S0068673500005253. ISSN 0068-6735. JSTOR 44696684.

- ^ Stanwick, Paul Edmund (2003). Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek Kings as Egyptian Pharaohs. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-292-77772-9.

- ^ a b c d Bagnall, R.S. (2000). Susan Walker (ed.). Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits in Roman Egypt. Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications. New York: Routledge. p. 27.

- ^ Bagnall (2000), pp. 28–29.

- ^ Alston, R. (1995). Soldier and Society in Roman Egypt: A Social History. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Fayoum mummy portraits". Egyptology Online. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ Broux, Y. Double Names and Elite Strategy in Roman Egypt. Studia Hellenistica 54 (Peeters Publishers, 2016).

- ^ Coussement, S. 'Because I am Greek': Polynymy as an Expression of Ethnicity in Ptolemaic Egypt. Studia Hellenistica 55 (Peeters Publishers, 2016).

- ^ Riggs, C. (2005). The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-191-53487-4.

- ^ Victor J. Katz (1998). A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, p. 184. Addison Wesley, ISBN 0-321-01618-1

- ^ a b Schuenemann, Verena; Peltzer, Alexander; Welte, Beatrix (30 May 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815694S. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

- ^ Bowman, Alan K. (1989). Egypt After the Pharaohs 332 BC-AD 642: From Alexander to the Arab Conquest. University of California Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-520-06665-6.

- ^ Dentition helps archaeologists to assess biological and ethnic population traits and relationships

- ^ Irish, JD (April 2006). "Who were the ancient Egyptians? Dental affinities among Neolithic through postdynastic peoples". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 129 (4): 529–543. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20261. PMID 16331657.

- ^ Schillaci, Michael A.; Irish, Joel D.; Wood, Carolan C. E. (5 June 2009). "Further analysis of the population history of ancient Egyptians". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (2): 235–243. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20976. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 19140183.

- ^ Encyclopedia Of Ancient Greece, Nigel Guy, Routledge Taylor and Francis group, p. 601

- ^ a b Borg (1998), p. 58.

- ^ "Panel Portrait of a Bearded Man | The Walters Art Museum". art.thewalters.org. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Nicola Hoesch (2000). "Mumienporträts". Der Neue Pauly. Vol. 8. p. 465.

- ^ Borg (1998), pp. 53–55.

- ^ Borg (1998), pp. 40–56.

- ^ Walker & Bierbrier (1997), pp. 17–20.

- ^ summarised in: Judith A. Corbelli: The Art of Death in Graeco-Roman Egypt, Princes Risborough 2006 ISBN 0-7478-0647-0

- ^ Borg (1998), p. 78.

- ^ Nicola Hoesch (2000). "Mumienporträts". Der Neue Pauly. Vol. 8. p. 464. Other scholars, e.g. Barbara Borg, suggest that they start under Tiberius.

- ^ Riggs (2005), p. 11.

- ^ Borg (1998), p. 31.

- ^ Borg (1998), pp. 88–101.

- ^ Borg (1998), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Walker & Bierbrier (1997), pp. 121–122, Nr. 117.

- ^ Walker & Bierbrier (1997), pp. 123–124, Nr. 119.

- ^ "Painting". www.sikyon.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015.

- ^ Other examples: a framed portrait from Hawara,[40] the image of a man flanked by two deities from the same site,[41] or the 6th century BC panels from Pitsa in Greece.[42]

- ^ "[image]". www.aisthesis.de. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012.

- ^ Kurt Weitzmann (1982). The Icon. (trans of Le Icone, Montadori 1981). London: Evans Brothers Ltd. p. 3. ISBN 0-237-45645-1.

- ^ "כך שני אמנים חילונים בנו מחדש את בית המקדש" [This is how two secular artists recreated the Temple in Jerusalem]. Haaretz (in Hebrew). Retrieved 3 December 2022.

Bibliography

[edit](chronological order)

- W. M. Flinders Petrie (1911). Roman Portraits and Memphis (IV). London. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007 – via ETANA (Electronic Tools and Ancient Near Eastern Archives).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Klaus Parlasca: Mumienporträts und verwandte Denkmäler, Wiesbaden 1966

- Klaus Parlasca: Ritratti di mummie, Repertorio d'arte dell'Egitto greco-romano Vol. B, 1-4, Rome 1969–2003 (Corpus of most of the known mummy portraits)

- Henning Wrede (1982). "Mumienporträts". Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Vol. IV. Wiesbaden. pp. 218–222.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Euphrosyne Doxiadis: The Mysterious Fayum Portraits. Thames and Hudson, 1995

- Barbara Borg: Mumienporträts. Chronologie und kultureller Kontext, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1742-5

- Susan Walker; Morris Bierbrier (1997). Ancient Faces, Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt. London. ISBN 0-7141-0989-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Barbara Borg (1998). "Der zierlichste Anblick der Welt ...". Ägyptische Porträtmumien. Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie/ Sonderhefte der Antiken Welt. Mainz am Rhein: Von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-2264-X; ISBN 3-8053-2263-1

- Wilfried Seipel (ed.): Bilder aus dem Wüstensand. Mumienportraits aus dem Ägyptischen Museum Kairo; eine Ausstellung des Kunsthistorischen Museums Wien, Milan/Wien/Ostfildern 1998; ISBN 88-8118-459-1;

- Klaus Parlasca; Hellmut Seemann (Hrsg.): Augenblicke. Mumienporträts und ägyptische Grabkunst aus römischer Zeit [zur Ausstellung Augenblicke – Mumienporträts und Ägyptische Grabkunst aus Römischer Zeit, in der Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt (30. Januar bis 11. April 1999)], München 1999, ISBN 3-7814-0423-4

- Nicola Hoesch (2000). "Mumienporträts". Der Neue Pauly. Vol. 8. pp. 464f.

- Susan Walker, ed. (2000). Ancient Faces. Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt. New York. ISBN 0-415-92744-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Paula Modersohn-Becker und die ägyptischen Mumienportraits ... Katalogbuch zur Ausstellung in Bremen, Kunstsammlung Böttcherstraße, 14.10.2007–24.2.2008, München 2007, ISBN 978-3-7774-3735-4

- Jan Picton, Stephen Quirke, Paul C. Roberts (ed): Living Images, Egyptian Funerary Portraits in the Petrie Museum, Walnut Creek CA 2007 ISBN 978-1-59874-251-0

External links

[edit]- "Unraveling the mysteries of ancient Egypt's spellbinding mummy portraits" CNN feature on Getty Museum project

- Mummy portraits Archived 3 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine in the Petrie Museum

- Proportion and personality in the Faiyum Portraits, A.J.N.W Prag, November 2002

- History of Encaustic Art

- Petrie's report from 1911

- Detailed discussion of mummy portraits (in English)

- Detailed discussion of mummy portraits (in French)

- Gallery of Fayum Mummy Portraits at Flickr

- 1st-century BC paintings

- 1st-century paintings

- 2nd-century paintings

- 3rd-century paintings

- 4th-century paintings

- Ancient Roman paintings

- Greek art

- Portraits of ancient Greece and Rome

- Roman Empire paintings

- Early Christian art

- Coptic art

- Hellenistic art

- Ancient Greek painting

- Roman Egypt

- Antiquities in the Pushkin Museum