Funk carioca

| Funk carioca | |

|---|---|

Audio sample of a simple funk carioca beat | |

| Other names |

|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Mid-1980s, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Typical instruments |

|

| Subgenres | |

Funk carioca (Brazilian Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈfɐ̃k(i) kɐɾiˈɔkɐ, - kaɾ-]), also known as favela funk, in other parts of the world as baile funk and Brazilian funk, or even simply funk, is a Brazilian hip hop-influenced music genre from Rio de Janeiro, taking influences from musical styles such as Miami bass and freestyle.[1][2]

In Brazil, "baile funk" refers not to the music, but to the actual parties or discotheques in which the music is played (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈbajli], from baile, meaning "ball").[3] Although originated in Rio, "funk carioca" has become increasingly popular among working classes in other parts of Brazil. In the whole country, funk carioca is most often simply known as "funk", although it is very musically different from the American genre of funk music.[4][5] In fact, it still shows its urban Afrobeat influences.

Overview

[edit]

Funk carioca was once a direct derivative of samba, Miami bass, Latin music, traditional African religious music, candomble, hip-hop and freestyle (another Miami-based genre) music from the US. The reason why these genres, very localized in the US, became popular and influential in Rio de Janeiro is due to proximity. Miami was a popular plane stop for Rio DJs to buy the latest American records. Along with the Miami influence came the longtime influence of the slave trade in Colonial Brazil. Various African religions like vodun, and candomble were brought with the enslaved Africans to the Americas. The same beat is found in Afro-religious music in the African diaspora and many black Brazilians identify as being part of this religion. This genre of music was mainly started by those in black communities in Brazil, therefore a boiling pot of influences to derive the hall-mark.

Many similar types of music genres can be found in Caribbean island nations such as; Jamaica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Barbados, Haiti, Puerto Rico, among others. Bounce music, which originates from New Orleans, Louisiana, also has a similar beat. New Orleans, originally a French territory, was a hub for Atlantic slave trade before it was sold to the United States. All of these areas with similar music genres retain the influence of American hip hop, African music and Latin music.[6]

During the 1970s, nightclubs in Rio de Janeiro played funk and soul music.[5] One of the bands that was formed in this period was Soul Grand Prix.[7]

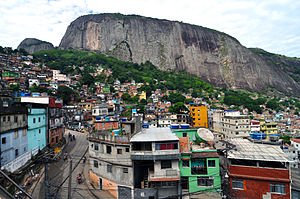

Funk carioca was popularized in the 1980s in Rio de Janeiro's favelas, the city's predominantly Afro-Brazilian slums. From the mid-1990s on, it was a mainstream phenomenon in Brazil. Funk songs discuss topics as varied as poverty, human dignity, racial pride of black people, sex, violence, and social injustice. Social analysts believe that funk carioca is a genuine expression of the severe social issues that burden the poor and black people in Rio.

According to DJ Marlboro, the main influence for the emergence of funk carioca was the single "Planet Rock" by Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force, released in 1982.[8]

Carioca in its early days were mostly loops of electronic drums from Miami bass or freestyle records and the 4–6 beat afrobeat tempo, while a few artists composed them with actual drum machines. The most common drum beat was a loop of DJ Battery Brain's "808 volt", commonly referred to as "Voltmix", though Hassan's "Pump Up the Party" is also notable.[9][10][11] Nowadays, carioca funk rhythms are mostly based on tamborzão rhythms instead of the older drum machine loops.

Melodies are usually sampled. Older songs typically chopped up freestyle samples for the melody, or had none at all. Modern funk uses a set of samples from various sources, notably horn and accordion stabs, as well as the horn intro to the "Rocky" theme. Funk carioca has always used a small catalog of rhythms and samples that almost all songs take from (commonly with several in the same song). Funk carioca songs can either be instrumental or include rapping, singing, or something in between the two. Popularized by Brazilians and other Afro-Latino people, the saying "Bum-Cha-Cha, Bum Cha-Cha", "Bum-Cha-Cha, Cha Cha" or even "Boom-Pop-Pop, Pop, Pop" is a representation of the beat that comes along in most funk songs. [1][12]

Funk carioca is different from the funk originated in the US. Starting in 1970, styles like bailes da pesada, black soul, shaft, and funk started to emerge in Rio de Janeiro. As time went on, DJs started to look for other rhythms of black music, but the original name did not remain. Funk carioca first emerged and is played throughout the state of Rio de Janeiro, but not only in the city of Rio, like Rio natives like to believe. Funk carioca is mostly appealing to the youth. In the decade of the 1980s, anthropologist Herman Vianna was the first social scientist to take funk as an object to study in his masters thesis, which gave origin to the book O Mundo Funk carioca, which translates to The Carioca Funk World (1988). During that decade, funk dances lost a bit of popularity due to the emergence of disco music, a pop version of soul and funk, especially after the release of the film Saturday Night Fever (1977) starring John Travolta and with its soundtrack of the band Bee Gees. At the time, the then teenager Fernando Luís Mattos da Matta was interested in the discotheque when listening to the program Cidade Disco Club on Radio City of Rio de Janeiro (102.9 FM). Years later, Fernando would adopt the nickname of DJ Marlboro and the radio would be known as the Rio "rock radio".

Bailes funk

[edit]The term baile funk is used to refer to the parties in which funk carioca is played. The history of these parties were important in shaping the Brazilian funk scene, and in fact predate the genre itself. In the late '60s, legendary Brazilian DJ and radio personality Big Boy (born Newton Alvarenga Duarte) was on a personal mission to introduce Brazil to the best sounds from around the globe.

Collecting records covering genres such as pop, rock, jazz, and soul from all over the world, he gained popularity on air for his wide taste of music, as well as the relaxed way of presenting his programs.[13] His success on air also attracted large audiences for parties he DJ'd in the Zona Sul area of Rio, which like his show, featured a wide array of different music. His sound mainly featured elements of rock, psych, and soul music, and many described the tunes he played as 'heavy'. At the same time, Ademir Lemos had been hosting his own block parties centering more around soul and funk, both of which had a growing audience in Brazil. The two eventually came to host parties together, infusing the heavy sounding records from Big Boy's (primarily) rock background with Lemos' funkier influences. Thus formed the Baile da Pesada, or "Heavy Dance", which brought (North American) funk music to the forefront of Rio's street scene as the city entered the 70's.[14]

For almost two decades afterwards, other DJs from the streets of Rio would use evolving forms of African-American and American music in their own block parties, put together by equipes de som (sound teams). Soul music became the immediate focus of the parties, and quickly ushered in a new wave of Brazilian soul artists to the mainstream. Soon, the soul movement was overshadowed by disco, but disco music was not easily embraced by many of the DJs hosting the bailes. Many of these DJs bought records from the US, particularly Miami given its closer proximity to Brazil. The DJs took a liking to various forms of hip-hop, most notably Miami bass and electro/freestyle, which changed the style of the bailes once again.[15] Still, the term funk remained in Rio's party scene. DJs would incorporate local sound with Miami bass beats, including their own lyrics in Portuguese. DJ Marlboro was the pioneer of this phenomenon, and was the first to engineer the sound that would become known in Rio as funk carioca.[16][17]

Subgenres

[edit]There are a number of subgenres derived from funk carioca.

Brega funk

[edit]Brega funk born in Recife, influenced by brega in the early 2010s in the Northeast region of Brazil. Unlike funk carioca, brega funk has a glossy sound that features glistening syncopated MIDI pianos, synths, often filtered guitars, and the distinct pitched metallic snares called caixas, vocal chops are a common companion to the wonky kick rhythm and up-down bass inherited from brega, and even though the genre commonly ranges from 160 to 180 BPM, the half-time beat makes it feel slower than other funk subgenres. An example of the Brega funk genre is the song "Parabéns" by Pabllo Vittar.[18][19]

Funk melody

[edit]Funk melody is based on electro rhythms but with a romantic lyrical approach.[20] It has been noted for being powered by female artists. Among the popular funk melody singers are Anitta, Perlla, Babi and Copacabana Beat.

Funk ostentação

[edit]Funk ostentação is a sub-genre of Rio de Janeiro funk created in São Paulo in 2008. The lyrical and thematic content of songs in this style focuses mainly on conspicuous consumption, as well as a focus on materialistic activities, glorification of style of urban life and ambitions to leave the favela. Since then, funk ostentação has been strongly associated with the emerging nova classe média (new middle class) in Brazil.[21]

Proibidão

[edit]Proibidão is a derivative of funk carioca related to prohibited practices. The content of the genre involves the sale of illegal drugs and the war against police agencies, as well as the glorification and praise of the drug cartels, similar to gangsta rap.

Rasteirinha

[edit]Rasteirinha or Raggafunk[22] is a slower style of Rio de Janeiro funk that rests around 96 BPM and uses atabaques, tambourines and beatboxing. It also incorporates influences from reggaeton and axé. "Fuleragem" by MC WM is the best known songs of the Rasteirinha genre.[23]

Rave funk

[edit]Rave funk is a mix of funk carioca and electronic music, created in 2016 by DJ GBR.[24] Among rave funk's most popular songs is "É Rave Que Fala Né" by Kevinho. Another notable example is "São Paulo", a 2024 collaboration between Brazilian singer Anitta and Canadian artist The Weeknd.[25]

Funk 150 BPM

[edit]In 2018, the Funk carioca of 150 beats per minute or 150 BPM was created by DJs Polyvox and Rennan da Penha.[26][27] In 2019, the funk carioca 150 BPM was adopted by carnival blocks.[28] "Ela É Do Tipo", by Kevin O Chris, is one of the most popular songs of the genre.[29]

Funk mandelão

[edit]Funk mandelão, also known as Ritmo dos Fluxos, is a subgenre that emerged in São Paulo in the late 2010s, inspired by the Baile do Mandela, a popular party in Praia Grande. The term “mandelão” comes from “Mandela”, a reference to the South African leader Nelson Mandela. Mandelão is characterized by having simple and repetitive lyrics. The musical production is minimalist and raw, with heavy beats and blown basses, that create a catchy and danceable rhythm. Some of the instruments used in mandelão are the piano, synthesizer, sampler and the computer. Funk mandelão is also marked by having its own choreography, which consists of fast and synchronized movements of the arms and legs.[30]

An example of the success of Mandelão was the song “Automotivo Bibi Fogosa”, sung by the Brazilian artist Bibi Babydoll, which reached the top of Spotify music charts in Ukraine in 2023 and reached #3 on both Belarus and Kazakhstan. It spread throughout the rest of Europe,[31] mainly in former Soviet Union states.

Brazilian phonk

[edit]Brazilian Phonk is a subgenre that combines elements of funk carioca and drift phonk, creating a distinct and aggressive sound, with lyrics that address topics such as violence, drugs, sex and ostentation. Both VanMilli and MC Binn are two of the heavy-hitters in the genre.[32] The term “Brazilian phonk” was popularized by the Norwegian producer William Rød, better known as Slowboy. The genre itself was popularised by Slowboy, FXRCE, $pidxrs808, $werve and many others.[33]

Pagofunk

[edit]Fusion of funk carioca with pagode,[34][35][36] the term also refers to parties where both genres are played,[37] the origins of the subgenre can be traced back to the mid 90s, in 1997, the duo Claudinho & Buchecha released the song Fuzuê on the album A Forma, the song uses a cavaquinho, an instrument present in genres such as samba, choro and pagode, in the lyrics, the duo pays tribute to pagode artists.[38] Grupo Raça was successful with "Ela sambou, eu dancei", written by Arlindo Cruz, A. Marques and Geraldão,[39] which alluded to funk carioca. In 2014, the song was reinterpreted with elements of carioca funk with Arlindo Cruz himself with Mr. Catra.[40]

Mc Leozinho, made use of the cavaquinho in the song Sente a pegada from 2008.[41] Artists such as MC Delano and Ludmilla also use the cavaquinho in some songs,[41] in 2015, Ludimilla also participated in a duet with the band Molejo in Polivalência from the album of the same name released in 2000, in 2020, she released Numanice, an EP dedicated to the pagode.[42][43]

Beat Bruxaria

[edit]A particularly extreme subgenre of funk originating in the late 2010s and early 2020s in São Paulo that combines funk vocals with loud reverb, four-on-the-floor kick drum drops, and over-the-top loud mixing to the point of extreme distortion.[44]

Recognition in Europe

[edit]Until the year 2000, funk carioca was only a regional phenomenon. Then the European media began to report its peculiar combination of music, social issues with a strong sexual appeal (often pornographic).

In 2001, for the first time, funk carioca tracks appeared on a non-Brazilian label. One example is the album Favela Chic, released by BMG. It contained three old-school funk carioca hits, including the song "Popozuda Rock n' Roll" by De Falla.[45]

In 2003, the tune Quem Que Caguetou (Follow Me Follow Me) by Black Alien & Speed,[46] which was not a big hit in Brazil, was then used in a sports car commercial in Europe, and it helped increase the popularity of funk carioca. Brazilian duo Tetine compiled and mixed the compilation Slum Dunk Presents Funk Carioca, released by British label Mr Bongo Records featuring funk artists such as Deize Tigrona, Taty Quebra Barraco, Bonde do Tigrão amongst others. From 2002 Bruno Verner and Eliete Mejorado also broadcast Funk Carioca and interviewed artists in their radio show Slum Dunk on Resonance Fm. Berlin music journalist and DJ Daniel Haaksman released the seminal CD-compilations Rio Baile Funk Favela Booty Beats in 2004 and More Favela Booty Beats in 2006 through Essay Recordings.[47] He launched the international career of Popozuda Rock n´Roll artist Edu K,[48] whose baile funk anthem was used in a soft drink commercial in Germany. Haaksman continued to produce and distribute many new baile funk records, especially the EP series "Funk Mundial"[49] and "Baile Funk Masters" on his label Man Recordings.

In 2004, dance clubs from Eastern Europe, mainly Romania and Bulgaria, increased the popularity of funk carioca due to the strong sexual appeal of the music and dance, also known as Bonde das Popozudas. Many funk carioca artists started to do shows abroad at that time. DJ Marlboro and Favela Chic Paris club were the pioneer travelers and producers. The funk carioca production was until then limited to playing in the ghettos and the Brazilian pop market. DJ Marlboro,[50] a major composer of funk carioca's tunes declared in 2006 in the Brazilian Isto É magazine how astonished he was with the sudden overseas interest in the genre. He would go on to travel in over 10 European countries.

In London, duo Tetine assembled a compilation album called Slum Dunk Presents Funk Carioca, which was released by Mr Bongo Records in 2004. Tetine also ran the weekly radio show Slum Dunk on London's radio art station Resonance Fm 104.4. Their radio show was entirely dedicated to funk carioca and worked as a platform for the duo to produce and organize a series of film programmes as well as interviews and gigs involving funk carioca artists from Rio. Tetine were also responsible for the first screening of the post-feminist documentary Eu Sou Feia Mas Tô Na Moda by filmmaker Denise Garcia which was co-produced by Tetine in London, and first shown in the city at the Slum Dunk Film Program at Brady Arts Centre in Bricklane in March 2005. Apart from this, Tetine also produced two albums with experimental DIY queer funk carioca tracks: Bonde do Tetão, released by Brazilian label Bizarre Records in 2004, and L.I.C.K My Favela, released by Kute Bash Records in 2005. Tetine also recorded with Deize Tigrona the track "I Go to the Doctor", included in the LP L.I.C.K My Favela in 2005 and later on their album Let Your X's Be Y's, released by Soul Jazz Records in 2008.

In Italy, Irma Records released the 2005 compilation Colors Music #4: Rio Funk. Many small labels (notably European label Arcade Mode and American labels Flamin´Hotz and Nossa) labels released several compilations and EPs in bootleg formats.

The artist MIA brought mainstream international popularity to funk carioca with her single Bucky Done Gun released in 2005,[citation needed] and brought attention to American DJ Diplo, who had worked on M.I.A.'s 2004 mixtape Piracy Funds Terrorism on the tracks Baile Funk One, Baile Funk Two, and Baile Funk Three.[51] Diplo made a bootleg mixtape, Favela on Blastin, in 2004[52] after Ivanna Bergese shared with him some compiled remix mixtapes of her performance act Yours Truly. He also produced documentary Favela on Blast, which was released in July 2010 and documents the role, culture, and character of funk carioca in Rio's favelas.[52]

Other indie video-documentaries have been made in Europe, especially in Germany and Sweden. These generally focused on the social issues in the favelas. One of the most famous of these series of documentaries is Mr Catra the faithful[53] (2005) by Danish filmmaker Andreas Rosforth Johnsen, broadcast by many European open and cable television channels.

London-based artist Sandra D'Angelo was the first Italian singer-producer to bring funk carioca to Italy.[citation needed] She performed in London with MC Gringo at Notting Hill Arts Club in 2008. She performed her baile funk productions for the contest Edison Change the Music in 2008. Sandra D'Angelo performed Baile Funk also in New York and produced tracks with EDU KA (Man Recordings) and DJ Amazing Clay from Rio.

In 2008, Berlin label Man Recordings released Gringão, the debut album by German MC Gringo — the only non-Brazilian MC performing in the bailes of Rio de Janeiro.

English indie pop band Everything Everything claim the drum patterns used on their Top 40 single Cough Cough were inspired by those used on Major Lazer's Pon de Floor, a funk carioca song.

Stylistic differences

[edit]In African music

[edit]Gqom, an electronic dance music genre from Durban, South Africa, is often conflated with baile funk due to similar origins in ghettos, heavy bass and associations with illegalities. Despite these parallels, gqom and baile funk are distinct, especially in their production styles. Over time, it became common for musical artists to integrate baile funk with gqom.[54][55][56][57][58]

Criticism

[edit]In Brazil, funk carioca lyrics are often criticized due to their violent and sexually explicit lyrics. Girls are called "cachorras" (bitches) and "popozudas" – women with large buttocks, and many songs revolve around sex. "Novinhas" (young/pubescent girls) are also a frequent theme in funk carioca songs. Some of these songs, however, are sung by women.

The extreme banalization of sex and the incitement of promiscuity is viewed as a negative aspect of the funk carioca culture. Besides the moral considerations, in favelas, where sanitary conditions are poor and sex education low, this might lead to public health and social issues. In such communities, definitive contraceptive methods are hardly available and due to lack of education and awareness, family planning is close to nonexistent. This environment results in unwanted pregnancies, population overgrowth, and eventually the growth of the communities (favelização).[59][60]

The glamorization of criminality in the favelas is also frequently viewed as another negative consequence of funk carioca. Some funk songs, belonging to a style known as "proibidão" ("the forbidden"), have very violent lyrics and are sometimes composed by drug-dealing gangs. Its themes include praising the murders of rival gang members and cops, intimidating opposers, claiming power over the favelas, robbery, drug use and the illicit life of drug dealers in general. Authorities view some of these lyrics as "recruiting" people to organized crime and inciting violence, and playing some of these songs are thus considered a crime.[61]

Due to the lack of regulation and the locations where they usually take place, "bailes funk" are also very crime prone environments. They are popular hot spots for drug trade and consumption, dealers display power frequenting the parties heavily armed,[62] and even murder rates are high.[63]

More popular funk carioca artists usually compose two different sets of similar lyrics for their songs: one gentler, more "appropriate" version, and another with a harsher, cruder set of lyrics (not unlike the concept of "clean" and "explicit" versions of songs). The first version is the one broadcast by local radio stations; the second is played in dance halls, parties, and in public by sound cars.[64] Recurrent lyric topics in funk carioca are explicit sexual positions, the funk party, the police force, and the life of slum dwellers in the favelas.[65] Another large part of the lyrics is the use of the world around them – mainly the poverty that has enveloped the area. This is usually denounced in the lyrics and the hope for a better life is carried through many of their messages.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Macia, Peter (May 6, 2005). "Rio Baile Funk: Favela Booty Beats". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 7, 2008.

- ^ Frere-Jones, Sasha (July 25, 2005). "Brazilian Wax". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. OCLC 320541675. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ [1] Archived November 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yúdice, George. "The Funkification of Rio". In Microphone Fiends, 193–220. London: Routledge, 1994.

- ^ a b Berrêdo, José Raphael (August 9, 2012). "Musical conta história de 4 décadas do funk no Brasil; relembre 40 hits" [Musical tells the story of 4 decades of funk in Brazil; remember 40 hits]. G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro. Archived from the original on August 15, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ tudobeleza (August 7, 2008). "Origins of Funk Carioca | Eyes On Brazil". Eyesonbrazil.wordpress.com. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ FP (June 5, 2022). "A noite em que a Soul Grand Prix enfrentou a Ditadura Militar". Saravá Cultural (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Albuquerque, Carlos (September 12, 2012). "Afrika Bambaataa celebra os 30 anos de 'Planet Rock'" [Afrika Bambaataa celebrates 30 years of ‘Planet Rock’]. O Globo (in Brazilian Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012.

- ^ Ribeiro, Eduardo (August 20, 2014). "A História do 'Tamborzão', a Levada Que Deu Cara ao Ritmo do Funk Carioca" [The Story of ‘Tamborzão’, the Beat That Gave Face to the Rhythm of Funk Carioca]. VICE (in Brazilian Portuguese). ISSN 1077-6788. OCLC 30856250. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020.

- ^ Caceres, Guillermo; Ferrari, Lucas; Palombini, Carlos (May 30, 2014). "A Era Lula/Tamborzão política e sonoridade" [The Lula / Tamborzão era and political sound]. Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros (in Portuguese) (58): 157. doi:10.11606/issn.2316-901X.v0i58p157-207.

- ^ "TAMBORZÃO baile funk beats (english version)". January 15, 2007. Archived from the original on December 14, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b "RIOFUNK.org – INFORMATION ABOUT BAILE FUNK !!!". Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ "Big Boy: o brasileiro que tocou, em primeira mão, um hit dos Beatles". EBC Rádios (in Brazilian Portuguese). May 4, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ Travae, Marques (April 10, 2013). "Black Rio: The rise of black music and dances | Black Women of Brazil". Black Brazil Today. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ "Funk Carioca Music: A Brief History of Funk Carioca". MasterClass. August 6, 2021.

- ^ Origins, Music (April 27, 2020). "30 years of Funk Carioca". The Music Origins Project. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ Palombini, Carlos (2010). "Notes on the historiography of Música soul and Funk carioca". Historia Actual Online (23 (Otoño)): 99–106. ISSN 1696-2060.

- ^ Pernambuco, Diario de (October 18, 2019). "Pabllo Vittar lança brega-funk em parceria com Márcio Victor, do Psirico | Viver: Diário de Pernambuco". Diário de Pernambuco.

- ^ "Pabllo Vittar lança o bregafunk 'Clima Quente' em parceria com Jerry Smith". Hashtag Pop. February 20, 2020.

- ^ Medeiros, Janaína. Funk carioca: crime ou cultura?. Terceiro Nome. p. 19. ISBN 9788587556745.

- ^ "Funk Ostentação symbolizes in SP emergegência da 'nova classe média'". Globo News (in Brazilian Portuguese). November 10, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ "Introducing Rasterinha, the Evolution of Baile Funk". Complex Networks.

- ^ "DJ Marlboro cria gênero Ragafunk em novo projeto". August 26, 2017.

- ^ "Five funk-rave explodes dance to us você conhecer". Kondzilla (in Brazilian Portuguese). December 7, 2019. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ "Anitta "dá à luz" música com The Weeknd; ouça "São Paulo"". CNN Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). October 30, 2024. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ "Funk carioca acelera e chega a 150 bpm em renovação liderada pelo DJ Polyvox". O Globo. March 8, 2018.

- ^ "Como o 150 BPM se tornou o ritmo dominante do funk carioca". www.vice.com.

- ^ "Blocos do carnaval de rua do Rio adotam 'funk 150 bpm'; veja vídeo". G1.

- ^ "Drake canta em português em remix de 'Ela é do Tipo', com MC Kevin O Chris". IstoE (in Brazilian Portuguese). November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Qual vai ser o hit do carnaval? De pagodão a mandelão, conheça 10 músicas que chegam fortes". February 10, 2023.

- ^ "Bibi Babydoll e o funk que virou hit na Ucrânia com gravação no cobertor e divulgação por R$ 30". August 16, 2023.

- ^ "Your Guide to Brazilian Phonk Music". Soundtrap. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ "Como música brasileira ficou em primeiro lugar nas mais ouvidas da Ucrânia". G1 (in Portuguese). Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ "Funk e pagode se misturam? Veja como isso vem acontecendo no universo do funk". kondzilla.com (in Portuguese). Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Mulheres no pagode: conheça cantoras que comandam ritmo em Salvador e lutam por reconhecimento e respeito". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "União da Ilha ensaia presença de pagode no meio da bateria e Laíla cria novo modelo de treino na rua". Carnavalesco (in Brazilian Portuguese). January 16, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "Pancadão da Turbininha". revista piauí (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ Francisco Oliveira (1997). "Claudinho & Buchecha – funk, charme, alegria e muito balanço editora - Editora Símbolo". Raça Brasil – Edição Extra (6).

- ^ "Geraldão". immub.org | IMMuB – O maior catálogo online da música brasileira (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ daniela.lima. "Arlindo Cruz comemora as 700 músicas gravadas e agradece a Deus em CD | Diversão | O Dia". odia.ig.com.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ a b "Cavaquinho pancadão: instrumento do samba invade o funk". O Globo (in Brazilian Portuguese). June 5, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Ludmilla entra com naturalidade no pagode em EP que transita entre a festa e a sofrência". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Cliquemusic : Disco : POLIVALÊNCIA". December 2, 2009. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Brazil-era, please tell me what kind of drugs your baile funk/funk carioca DJs are on". resetera.com. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ "Various – Favela Chic: Funk Favela". discogs. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Tejo, Black Alien & Speed – Follow Me Follow Me (Quem Que Caguetou?)". discogs. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Rio Baile Funk: Favela Booty Beats". Archived from the original on September 26, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ "Edu K". Manrecordings.com. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ "Funk Mundial".

- ^ "É BIG MIX O MANÉ".

- ^ "M.I.A. – Piracy Funds Terrorism Volume 1". discogs. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ a b "Favela on Blast".

- ^ "Andreas Rosforth Johnsen – Official website". Rosforth.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Gqom is the explosive South African sound bursting into Europe". Mixmag. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ "Listen To A Thrilling New Lafawndah Song In Her Mix For Kenzo". The FADER. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ Staff Reporter (December 7, 2018). "DJ Lag: The gqom whisperer comes home". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ "Moonchild Sanelly is on the prowl in the "Where De Dee Kat" video". The FADER. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ "An introduction to baile funk's abrasive, addictive new wave". The FADER. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ "Folha Online – Cotidiano – Atlas aponta natalidade maior que a média em favelas da Grande SP – 22/11/2006". .folha.uol.com.br. November 22, 2006. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ "G1 – Rio de Janeiro: notícias e vídeos da Globo". Rjtv.globo.com. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ "Vídeo » Proibidões nos bailes funks das favelas do Rio de janeiro". OsMelhoresVideos.net. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Carolina Lauriano Do G1, no Rio. "G1 > Edição Rio de Janeiro – NOTÍCIAS – Vagner Love nega conhecer homens que aparecem armados em vídeo". G1.globo.com. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "G1 – O Portal de Notícias da Globo – BUSCA". Busca2.globo.com. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Sansone, Livio. "The Localization of Global Funk in Bahia and Rio." Brazilian Popular Music & Globalization, 139. London: Routledge, 2002

- ^ Artists, Various (July 21, 2005). "The Sound of Brazil's Funk Carioca: NPR Music". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

External links

[edit]- "Ghetto Fabulous" Observer Music Monthly article on Baile Funk by Alex Bellos 2005

- "Samba, That's So Last Year" article by Alex Bellos at The Guardian 2004

- "In The Fight Club Of Rio" article on "corridor balls" at Free Radical by Canadian Nicole Veash 2000

- Article with Baile Funk master Sany Pitbull by Sabrina Fidalgo at Musibrasil 2007

- "The Funk Phenomenon" article by Bruno Natal at XLR8R magazine 2005

- Funk Carioca and Música Soul by Carlos Palombini