Armet

The armet is a type of combat helmet which was developed in the 15th century. It was extensively used in Italy, France, England, the Low Countries and Spain. It was distinguished by being the first helmet of its era to completely enclose the head while being compact and light enough to move with the wearer. Its use was essentially restricted to the fully armoured man-at-arms.

Appearance and origins

[edit]

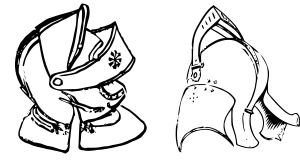

As the armet was fully enclosing, and narrowed to follow the contours of the neck and throat, it had to have a mechanical means of opening and closing to enable it to be worn. The typical armet consisted of four pieces: the skull, the two large hinged cheek-pieces which locked at the front over the chin, and a visor which had a double pivot, one either side of the skull. The cheek-pieces opened laterally by means of horizontal hinges; when closed they overlapped at the chin, fastening by a spring-pin which engaged in a corresponding hole, or by a swivel-hook and pierced staple. A reinforcement for the bottom half of the face, known as a wrapper, was sometimes added; its straps were protected by a metal disc at the base of the skull piece called a rondel. The visor attached to each pivot via hinges with removable pins, as in the later examples of the bascinet. This method remained in use until c. 1520, after which the hinge disappeared and the visor had a solid connection to its pivot. The earlier armet often had a small aventail, a piece of mail attached to the bottom edge of each cheek-piece.[1]

The earliest surviving armet dates to 1420 and was made in Milan.[2] An Italian origin for this type of helmet therefore seems to be indicated. The innovation of a reduced skull and large hinged cheek pieces was such a radical departure from previous forms of helmet that it is highly probable that the armet resulted from the invention of a single armourer or soldier, and not as the result of evolution from earlier forms.[2] However, a number of Italian bascinets dating to c. 1400 (sometimes termed 'Venetian great bascinets') were discovered in Chalcis, Greece; these possess a single hinged cheekpiece (the other being immobile). This may have had some influence on the development of the armet.[3]

Use and variations

[edit]

The armet reached the height of its popularity during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, when western European full plate armour had been perfected. The term armet was often applied in contemporary usage to any fully enclosing helmet, however, modern scholarship draws a distinction between the armet and the outwardly similar close helmet (or close helm) on the basis of their construction, especially their means of opening to allow them to be worn. While an armet had two large cheekpieces hinged at the skull and opened laterally, a close helmet instead had a kind of movable bevor which was attached to the same pivot points as its visor and opened vertically.[4]

The classic armet had a narrow extension to the back of the skull reaching down to the nape of the neck, and the cheekpieces were hinged, horizontally, directly from the main part of the skull. From about 1515, the Germans produced a variant armet where the downward extension of the skull was made much wider, reaching as far forward as the ears. The cheekpieces on this type of helmet opened sideways, on vertical hinges on the edges of this wider neck element.[5] The high-quality English Greenwich armours often included this type of armet from c. 1525. Greenwich-made armets adopted the elegant two-piece visor found on contemporary close helmets; armets of this form were manufactured until as late as 1615. The lower edge of such helmets often closed over a flange in the upper edge of a gorget-piece. The helmet could then rotate without allowing a gap in the armour that a weapon point could enter.[6]

The armet is found in many contemporary pieces of artwork, such as Paolo Uccello's The Battle of San Romano, and is almost always shown as part of a Milanese armor. These depictions show armets worn with tall and elaborate crests, largely of feathered plumes; however, no surviving armets have similar crests and very few show obvious provision for the attachment of such crests.[7]

The armet was most popular in Italy, however, in England, France and Spain it was widely used by men-at-arms alongside the sallet, whilst in Germany the latter helmet was much more common. It is believed that the close helmet resulted from a combination of various elements derived from each of the preceding helmet types.

References

[edit]- ^ Oakeshott 2000, pp. 118–121.

- ^ a b Oakeshott 2000, p. 118.

- ^ Ffolkes, C. (1911) On Italian Armour from Chalcis in the Ethnological Museum at Athens, ARCHEOLOGIA 62, Part II Feb., 1911

- ^ Oakeshott 2000, p. 121.

- ^ Oakeshott 2000, p. 123.

- ^ Gravett 2006, pp. 20, 62.

- ^ Oakeshott 2000, pp. 119–120.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gravett, Christopher (2006). Tudor knight. Oxford New York: Osprey Pub. ISBN 978-1-84176-970-7.

- Oakeshott, R. Ewart (2000). European weapons and armour : from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution. Rochester, NY: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-789-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Nickel, H, ed. (1982). The Art of Chivalry : European arms and armor from the Metropolitan Museum of Art : an exhibition. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The American Federation of Arts.