David Scott

David Scott | |

|---|---|

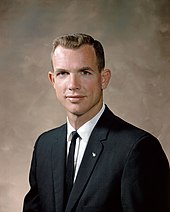

Scott in 1971 | |

| Born | David Randolph Scott June 6, 1932 San Antonio, Texas, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Awards | |

| Space career | |

| NASA astronaut | |

| Rank | Colonel, USAF |

Time in space | 22d 18h 54m[1] |

| Selection | NASA Group 3 (1963) |

Total EVAs | 5 Stand-up EVA on Apollo 9 4 EVAs on Apollo 15 (1st EVA was a stand-up, while 3 EVAs were on the lunar surface) |

Total EVA time | 20h 46m[1] |

| Missions | |

Mission insignia |  |

| Retirement | September 30, 1977[1] |

David Randolph Scott (born June 6, 1932) is an American retired test pilot and NASA astronaut who was the seventh person to walk on the Moon. Selected as part of the third group of astronauts in 1963, Scott flew to space three times and commanded Apollo 15, the fourth lunar landing; he is one of four surviving Moon walkers and the only living commander of a spacecraft that landed on the Moon.[2]

Before becoming an astronaut, Scott graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point and joined the Air Force. After serving as a fighter pilot in Europe, he graduated from the Air Force Experimental Test Pilot School (Class 62C) and the Aerospace Research Pilot School (Class IV). Scott retired from the Air Force in 1975 with the rank of colonel, and more than 5,600 hours of logged flying time.

As an astronaut, Scott made his first flight into space as a pilot of the Gemini 8 mission, along with Neil Armstrong, in March 1966, spending just under eleven hours in low Earth orbit. He would have been the second American astronaut to walk in space had Gemini 8 not made an emergency abort. Scott then spent ten days in orbit in March 1969 as Command Module Pilot of Apollo 9, a mission that extensively tested the Apollo spacecraft, along with Commander James McDivitt and Lunar Module Pilot Rusty Schweickart.

After backing up Apollo 12, Scott made his third and final flight into space as commander of the Apollo 15 mission, the fourth crewed lunar landing and the first J mission. Scott and James Irwin remained on the Moon for three days. Following their return to Earth, Scott and his crewmates fell from favor with NASA after it was disclosed that they had carried four hundred unauthorized postal covers to the Moon. After serving as director of NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center in California, Scott retired from the agency in 1977. Since then, he has worked on a number of space-related projects and served as a consultant for several films about the space program, including Apollo 13.

Early life and education

[edit]Scott was born June 6, 1932, at Randolph Field (for which he received his middle name) near San Antonio, Texas.[3][4] His father was Tom William Scott (1902–1988), a fighter pilot in the United States Army Air Corps who would rise to the rank of brigadier general; his mother was Marian Scott (née Davis; 1904–1999).[5] Scott lived his earliest years at Randolph Field, where his father was stationed, before moving to an air base in Indiana, and then in 1936 to Manila in the Philippines, then under U.S. rule. David remembered his father as a strict disciplinarian. The family returned to the United States in December 1939. By the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the family was living in San Antonio again; shortly thereafter Tom Scott was deployed overseas.[6]

As it was felt that he needed more discipline than he would receive with his father gone for three years, David was sent to Texas Military Institute, spending his summers at Hermosa Beach in California with his father's college friend, David Shattuck, after whom he had been named. Determined to become a pilot like his father, David built many model airplanes and watched with fascination war films about flying. By the time of Tom Scott's return, David was old enough to be allowed to go up in a military aircraft with him, and in David Scott's autobiography remembered it as "the most exciting thing I had ever experienced".[7]

David Scott was active in the Boy Scouts of America, achieving its second-highest rank, Life Scout.[8] With Tom Scott assigned to March Air Force Base near Riverside, California, David attended Riverside Polytechnic High School, where he joined the swimming team and set several state and local records. Before David could finish high school, Tom Scott was transferred to Washington, D.C., and after some discussion as to whether he should remain in California to graduate, David attended Western High School in Washington, graduating in June 1949.[9]

David Scott wanted an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point but lacked connections to secure one.[10] He took a government civil service examination for competitive appointments and accepted a swimming scholarship to the University of Michigan where he was an honor student in the engineering school. In the spring of 1950, he received and accepted an invitation to attend West Point.[10] Scott attended Michigan on a swimming scholarship, set a freshman record in the 440-yard freestyle, and the team captain during Scott's year there, Jack Craigie, recalled that the West Point swimming coach, Gordon Chalmers, was happy to get Scott from Michigan, one of the dominant programs of the time.[11]

Scott still wanted to fly and wanted to be commissioned in the newly established United States Air Force (USAF).[12] The Air Force Academy was founded in 1954, the year Scott graduated from West Point; an interim arrangement had been made whereby a quarter of West Point and United States Naval Academy graduates could volunteer to be commissioned as Air Force officers.[13] Earning a Bachelor of Science degree in military science,[14] Scott graduated 5th in his class of 633 and was commissioned in the Air Force.[15]

Air Force pilot

[edit]Scott did six months of primary pilot training at Marana Air Base in Arizona, beginning there in July 1954.[15] He completed Undergraduate Pilot Training at Webb Air Force Base, Texas, in 1955, then went through gunnery training at Laughlin Air Force Base, Texas, and Luke Air Force Base, Arizona.[16]

From April 1956 to July 1960, Scott flew with the 32nd Tactical Fighter Squadron at Soesterberg Air Base, Netherlands, flying F-86 Sabres and F-100 Super Sabres.[16] The weather there was often poor, and Scott's piloting skills were tested.[17] Once, he had to land his plane on a golf course after a flameout. On another, he barely made it to a Dutch base on the edge of the North Sea.[18] Scott served in Europe during the Cold War and tensions were often high between the U.S. and Soviet Union. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, his squadron was placed on the highest alert for weeks but was stood down without going into combat.[19]

Scott hoped to advance his career by becoming a test pilot, to be trained at Edwards Air Force Base. He was counseled that the best way to get into test pilot school was to gain a graduate degree in aeronautics. Accordingly, he applied to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and was accepted.[20] He received both a Master of Science degree in Aeronautics/Astronautics and the degree of Engineer in Aeronautics/Astronautics (the E.A.A. degree) from MIT in 1962.[21]

After receiving these degrees, Scott was stunned to receive orders from the Air Force to report to the new Air Force Academy as a professor, rather than to test pilot school. Although challenging orders was strongly discouraged, Scott went to the Pentagon and found a sympathetic ear from a colonel. Scott received changed orders to report to Edwards.[22]

Scott reported to the Air Force Experimental Flight Test Pilot School at Edwards in July 1962. The commandant of the school was Chuck Yeager, the first person to break the sound barrier, whom Scott idolized; Scott got to fly several times with him. Scott graduated top pilot in his class. He was selected for the Aerospace Research Pilot School, also at Edwards, where those intended as Air Force astronauts were trained. There he learned how to control aircraft, such as the Lockheed NF-104A, at altitudes of up to 100,000 feet (30,000 m).[23][24]

NASA career

[edit]

In applying to be part of the third group of astronauts in 1963, Scott intended only a temporary detour from a mainstream military career; he expected to fly in space a couple of times and then return to the Air Force.[24] He was accepted as one of the fourteen Group 3 astronauts later that year.[25]

Scott's initial assignment was as an astronaut representative at MIT supervising the development of the Apollo Guidance Computer. He spent most of 1964 and 1965 in residence in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[26][27] He served as backup CAPCOM during Gemini 4 and as a CAPCOM during Gemini 5.[28]

Gemini 8

[edit]After the conclusion of Gemini 5, Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton informed Scott that he would fly with Neil Armstrong on Gemini 8.[29] This made Scott the first Group 3 astronaut to become a member of a prime crew, and this without having served on a backup crew. Scott was highly regarded by his colleagues for his piloting credentials; another Group 3 astronaut, Michael Collins, wrote later that Scott's selection to fly with Armstrong helped convince him that NASA knew what it was doing.[30]

Scott found Armstrong something of a taskmaster, but the two men greatly respected each other and worked well together.[31] They spent most of the seven months before launch in each other's company. One part of the training that Scott undertook without Armstrong was riding the Vomit Comet, where he practiced in preparation for a planned spacewalk.[32]

On March 16, 1966, Armstrong and Scott were launched into space, a flight originally planned to last three days. The Agena rocket with which they were to dock had been launched an hour and forty minutes earlier. They carefully approached and docked with the Agena, the first docking ever accomplished in space. However, after the docking, there was unexpected movement by the joined craft. Mission Control was out of touch during this portion of the orbit, and the astronauts' belief that the Agena was causing the problem proved incorrect, for once they performed an emergency undocking, the spin only got worse. With the spacecraft spinning, there was a risk of the astronauts blacking out or the Gemini vehicle disintegrating. The problem was one of the craft's Orbit Attitude and Maneuvering System (OAMS) thrusters firing unexpectedly; the crew shut down those thrusters, and Armstrong activated the Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters to negate the spin. The RCS thrusters were to be used for reentry, and the mission rules said if they were activated early, Gemini 8 had to return to Earth.[33] Gemini 8 splashed down in the Western Pacific on the day of launch; the mission lasted only ten hours, and the early termination meant that Scott's spacewalk was scrubbed.[34]

According to Francis French and Colin Burgess in their book on NASA and the Space Race, "Scott, in particular, had shown incredible presence of mind during the unexpected events of the Gemini 8 mission. Even in the middle of an emergency, out of contact with Mission Control, he had thought to reenable ground control command of the Agena before the two vehicles separated."[35] This allowed NASA to check the Agena from the ground, and use it for a subsequent Gemini mission. Scott's competence was recognized by NASA when, five days after the brief flight, he was assigned to an Apollo crew.[36] Along with Armstrong, Scott received the NASA Exceptional Service Medal,[37] and the Air Force awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross as well. He was also promoted to lieutenant colonel.[38]

Apollo 9

[edit]

Scott's Apollo assignment was as backup senior pilot/navigator for what would become known as Apollo 1, scheduled for launch in February 1967, with Jim McDivitt as backup commander and Russell Schweickart as pilot. In that capacity, they spent much of their time at North American Rockwell's plant in Downey, California, where the command and service module (CSM) for that mission was under construction.[39]

By January 1967, Scott's crew had been assigned as prime crew for a subsequent Apollo mission and were at Downey on January 27 when a fire took the lives of the Apollo 1 prime crew during a pre-launch test.[40] During the fire, the inward-opening hatch had proved impossible for the astronauts to open, and Scott's post-fire assignment, with all flights put on hold amid a complete review of the Apollo program, was to serve on the team designing a simpler, outward-opening hatch.[41]

After the pause, Scott's crew was assigned to Apollo 8, intended to be an Earth-orbit test of the full Apollo spacecraft, including the Lunar Module (LM).[42] There were delays in the development of the lunar module and in August 1968, NASA official George Low proposed that if Apollo 7 in October went well, Apollo 8 should go to lunar orbit without a Lunar Module, so as not to hold up the program. The Earth-orbit test would become Apollo 9.[43] McDivitt was offered Apollo 8 by Slayton, but turned it down on behalf of his crew (who fully agreed), preferring to wait for Apollo 9, which would involve extensive testing of the spacecraft and was dubbed "a test pilot's dream".[44]

As command module pilot for Apollo 9 Scott's responsibilities were heavy. The LM was to separate from the CSM during the mission; if it failed to return, Scott would have to run the entire spacecraft for reentry, normally a three-man job. He would also have to go rescue the LM if it could not perform the rendezvous, and if it could not dock, would have to assist McDivitt and Schweickart in performing an extravehicular activity (EVA) or spacewalk, back to the CSM.[45] Scott was somewhat unhappy, though, that CSM-103, which he had worked on extensively, would stay with Apollo 8, with Apollo 9 given CSM-104.[46]

The planned February 28, 1969, launch date was postponed as all three astronauts had head colds, and NASA was wary of medical issues in space after problems on Apollo 7 and Apollo 8.[47] The launch took place on March 3, 1969. Within hours of launch, Scott had performed a maneuver essential to the lunar landing by piloting the CSM Gumdrop away from the S-IVB rocket stage, then turned Gumdrop around and docked with the LM Spider still attached to the S-IVB, before the combined spacecraft separated from the rocket.[48]

Schweickart vomited twice on the third day in space, suffering from space adaptation syndrome. He was supposed to do a spacewalk from the LM's hatch to that of the CM the following day, proving that this could be done under emergency conditions, but because of concerns about his condition, simply exited the LM while Scott stood in the CM's hatch, bringing in experiments and photographing Schweickart. On the fifth day in space, March 7, McDivitt and Schweickart in the LM Spider flew away from the CSM while Scott remained in Gumdrop, making him the first American astronaut to be alone in space since the Mercury program. After the redocking, Spider was jettisoned.[49] The LM had gone over 100 miles (160 km) from the CSM during the test.[16]

The remainder of the mission was devoted to tests of the command module, mostly performed by Scott; Schweickart called these days "Dave Scott's mission"; McDivitt and Schweickart had much time to observe the Earth as Scott worked. The mission stayed in space one orbit longer than planned due to rough seas in the Atlantic Ocean recovery zone.[50] Apollo 9 splashed down on March 13, 1969, less than four nautical miles (7 km) from the helicopter carrier USS Guadalcanal,[16] 180 miles (290 km) east of the Bahamas.[51]

Apollo 15

[edit]

Scott was deemed to have performed his duties well, and on April 10, 1969, was named backup commander of Apollo 12,[52] with Al Worden as command module pilot and James Irwin as lunar module pilot. McDivitt had chosen to go into NASA management, and Slayton had seen Scott as a potential crew commander; Worden and Irwin were working on the support crews for Apollo 9 and Apollo 10, respectively. Schweickart was ruled out due to the space sickness episode. This put the three in line to be the prime crew for Apollo 15.[53] Scott's status as backup commander of the next flight allowed him to sit in the Mission Control room as Apollo 11, with his old crewmate Armstrong in command, landed on the Moon.[54] That Scott, Worden, and Irwin would be the crew of Apollo 15 was announced on March 26, 1970.[55]

Apollo 15 would be the first J Mission, which emphasized scientific research, with longer stays on the Moon's surface and the use of the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV). Already having an interest in geology, Scott made time during the training for his crew to go on field trips with Caltech geologist Lee Silver. The scientists were divided over where Apollo 15 should land; Scott's argument for the area of Hadley Rille won the day. As time dwindled towards the launch date, Scott pushed to make the field trips more like what they would encounter on the lunar surface, with mock backpacks simulating what they would wear on the Moon, and from November 1970 onwards, the training version of the LRV.[56]

Apollo 15 launched from Kennedy Space Center's Launch Complex 39A on July 26, 1971. The outward flight to the Moon's orbit saw only minor difficulties, and the mission entered lunar orbit without incident.[57] The descent to the Moon by the LM Falcon, with Scott and Irwin aboard, took place on the late afternoon of July 30, with Scott as commander attempting the landing.[58] Despite difficulties caused by the computer-controlled flight path being to the south of what was planned, Scott assumed manual control for the final descent, and successfully landed the Falcon within the designated landing zone.[59]

Man must explore. And this is exploration at its greatest.

— David Scott[60]

After landing, Scott and Irwin donned the helmets and gloves of their pressure suits and Scott performed the first and only stand-up EVA on the lunar surface,[nb 1] by poking his head and upper body out of the docking port on top of the LM. He took panoramic photographs of the surrounding area from an elevated position and scouted the terrain they would be driving across the next day.[16] After deploying the LRV from its folded-up position on the side of the LM's descent stage, Scott drove with Irwin in the direction of Hadley Rille. Once there, Scott marveled at the beauty of the scene. While their exploits were followed by a television camera mounted on the Rover and controlled from Earth, Scott and Irwin took samples of the lunar surface, including the rock Great Scott named after the astronaut, before returning to the LM to set up the ALSEP, the experiments that were to continue to run after their departure.[62]

The second traverse, the following day (August 1) was to the slope of Mount Hadley Delta. At Spur Crater, they discovered one of the most famous lunar samples, a plagioclase-rich anorthosite from the early lunar crust, that was later dubbed the Genesis Rock by the press. On the third day, August 2, they went on their final moonwalk, an excursion cut short by problems with retrieving a core sample. On their return to the LM, Scott, before the television camera, dropped a hammer and a feather to demonstrate Galileo's theory that objects in a vacuum will drop at the same rate. After driving the LRV to a position where the camera could view Falcon's takeoff, Scott left a memorial to the astronauts and cosmonauts who had died to advance space exploration. This consisted of a plaque bearing their names, and a small aluminum sculpture, Fallen Astronaut, by Paul Van Hoeydonck. Once this was done, Scott re-entered the LM, and soon thereafter, Falcon lifted off from the Moon.[57][63]

Apollo 15 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean north of Honolulu on August 7, 1971. The first crew to land on the Moon and not be quarantined on return, the astronauts were flown to Houston, and after debriefing, were sent off on the usual circuit of addresses to Congress, celebrations, and foreign trips that met returning Apollo astronauts. Scott regretted the lack of quarantine, which he felt would have given them time to recover from the flight, as the demands on their time were heavy.[64]

Postal covers incident

[edit]

The crew had arranged with a friend named Horst Eiermann to carry postal covers to the Moon in exchange for about $7,000 for each astronaut.[65] Slayton had issued regulations that personal items taken in spacecraft must be listed for his approval;[66] which was not done for the covers.[67] Scott carried the covers into the CM in his spacesuit; they were transferred to the LM en route to the Moon and landed there with the astronauts.[68] Scott sent 100 of them to Eiermann, and in late 1971, against the astronauts' wishes, the covers were offered for sale by West German stamp dealer Hermann Sieger.[69] The astronauts returned the money,[70] but in April 1972, Slayton learned of the unauthorized covers[71] and had Scott, Worden, and Irwin removed as backup crew members for Apollo 17. The matter became public in June 1972,[72] and the astronauts were reprimanded for poor judgment by NASA and the Air Force the following month.[73][74] The covers that the crew still had were initially impounded by NASA but were in 1983 returned to the astronauts in an out-of-court settlement, as the government felt it could not successfully defend the lawsuit, and that NASA either authorized the covers to be flown or was aware of them.[75]

The press release that announced the reprimands, dated July 11, 1972, stated that the astronauts' "actions will be given due consideration in their selection for future assignment",[76] something that made it extremely unlikely that they would be selected to fly in space again.[77] Newsweek reported that "there are no forthcoming missions for which he [Scott] is being considered".[78] Scott related in his autobiography that Alan Shepard, then head of the Astronaut Office, had offered him the choice between backing up Apollo 17 or serving as a special assistant on the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the first joint mission with the Soviet Union; Scott had chosen the latter.[79] Although a NASA spokesman had stated that Scott had no choice but to leave the Astronaut Corps, and this was reproduced in the press, Slayton's supervisor, Christopher C. Kraft, stated that the Public Affairs Office at NASA had erred, and the transfer was not a further rebuke.[80]

NASA management

[edit]

In his role with Apollo-Soyuz, Scott traveled to Moscow, leading a team of technical experts. There he met the commander of the Soviet part of the mission, Alexei Leonov, with whom he would later write a joint autobiography.[81] In 1973 Scott was offered the job of deputy director of NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, located at Edwards, a place Scott had long loved. This allowed Scott to fly aircraft that reached the edge of space, and let him renew his acquaintance with the retired Chuck Yeager who was there as a consulting test pilot, and to whom Scott granted flying privileges.[82]

On April 18, 1975, at age 42, Scott became the Center Director at Dryden.[1] This was a civilian appointment, and to accept it, Scott retired from the Air Force in March 1975 with the rank of colonel.[83] Kraft wrote in his memoirs that Scott's appointment "pissed off Deke to his eyebrows".[84] Scott found the work interesting and exciting, but with budget cuts and the forthcoming end of Approach and Landing Tests for the Space Shuttle, in 1977 he decided it was time to leave NASA[85] and retired from the agency on September 30, 1977.[1]

Post-NASA career

[edit]

Entering the private sector, Scott founded Scott Science and Technology, Inc.[1] In the late 1970s and the 1980s, Scott worked on several government projects, including designing the astronaut training for a proposed Air Force version of the Space Shuttle.[86] One of Scott's firms went out of business after the 1986 Challenger disaster; though the company played no part in the disaster, subsequent redesign of parts of the shuttle eliminated Scott's firm's role.[87] After Challenger, Scott served four years on the Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee, formed to advise the Secretary of Transportation on the possible conversion of ICBMs to launch vehicles.[88] In 1992 Scott was found by a Prescott, Arizona, court to have defrauded nine investors in a partnership organized by him.[87] He was ordered to pay roughly $400,000 to investors in the partnership, which was to create technology to prevent aircraft mechanical breakdowns, but which was never developed.[89]

Scott was a commentator for British television on the first Space Shuttle flight (STS-1) in April 1981.[88] He also was a consultant on the film Apollo 13 and for the 1998 HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon,[88] in which he was portrayed by Brett Cullen.[90] Scott consulted on the 3D IMAX film, Magnificent Desolation (2005), showing Apollo astronauts on the Moon, and produced by Tom Hanks and the IMAX Corporation.[88] He is one of the astronauts featured in the 2007 book and documentary In the Shadow of the Moon.[91]

From 2003 to 2004, Scott was a consultant on the BBC TV series Space Odyssey: Voyage To The Planets.[92] In 2004, he and Leonov began work on a dual biography/history of the "Space Race" between the United States and the Soviet Union. The book, Two Sides of the Moon: Our Story of the Cold War Space Race, was published in 2006. Armstrong and Hanks both wrote introductions to the book. Scott has worked on the Brown University science teams for the Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter. For NASA, he has worked on the 500-Day Lunar Exploration Study and as a collaborator on the research investigation entitled "Advanced Visualization in Solar System Exploration and Research (ADVISER): Optimizing the Science Return from the Moon and Mars".[88]

Scott had taken two Bulova timepieces, a wristwatch and a stopwatch, with him to the Moon without advance authorization from Slayton.[93] Scott wore the wristwatch on the third EVA, after his NASA-issued Omega Speedmaster lost its crystal. He sold the Bulova watch in 2015 for $1.625 million, after which the company marketed similar timepieces, whose accompanying material mentioned Scott and Apollo 15. Scott sued in federal court in 2017, alleging Bulova and Kay Jewelers were wrongfully using his name and image for commercial purposes, and in April 2018, a federal magistrate ruled he could proceed on some of his claims.[94] The case was dismissed by agreement of the parties in August 2018,[95] and in 2021, Bulova marked the fiftieth anniversary of Apollo 15 with the issuance of a commemorative watch.[96]

Personal life

[edit]

In 1959 Scott married his first wife, Ann Lurton Ott. They had two children. In 2000, it was reported that he was engaged to British TV presenter Anna Ford; at the time he was still married to Ann Scott, although separated. His relationship with Ford had begun in 1999.[87] By 2001, Scott and Ford had separated.[97] He subsequently married Margaret Black, former vice-chairman of Morgan Stanley.[88] David Scott and Margaret Black-Scott reside in Los Angeles.[88]

Awards, honors, and organizations

[edit]Deputy Administrator Robert Seamans presented Scott and Armstrong the NASA Exceptional Service Medal in 1966 for their Gemini flight.[38][98] Scott was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for the Gemini 8 flight.[99] Vice President Spiro Agnew presented the Apollo 9 crew with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal. At the ceremony, Agnew said, "I am proud that America has forged to the forefront and established the leadership in space to match our new leadership on Earth."[100] Scott received the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal for the Apollo 9 mission.[99]

Agnew also gave the Apollo 15 crew the NASA Distinguished Service Medal.[101] Scott earned his second Air Force Distinguished Service Medal for Apollo 15.[99] On September 15, 1971, the city of Chicago hosted the Apollo 15 crew in a parade attended by more than 200,000 people. Mayor Daley presented the crew with honorary citizenship medals.[102] On August 25, 1971, the Apollo 15 crew were honored with a ticker-tape parade in New York City. The city bestowed them with gold medals. Later that day, U.N. Secretary General Thant awarded the trio the first United Nations Peace Medal.[103][104] At the Air Force Association's annual dinner dance in September 1971, the Apollo 15 crew were presented with the David C. Schilling Trophy, the association's top flight award. Scott presented the Air Force and Air Force Association with items they flew to the Moon: sheet music of "Into the Wild Blue Yonder" and a U.S. Air Force flag.[105] The Apollo 15 crew and Robert Gilruth (director of the Manned Spacecraft Center) were awarded the 1971 Robert J. Collier Trophy, an annual award for the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics.[106] Scott received the De la Vaulx Medal, the Gold Space Medal, and the V.M. Komorav Diploma from Fédération Aéronautique Internationale for 1971 for his role in the Apollo 15 flight.[107] Scott was awarded his third NASA Distinguished Service Medal in 1978.[16]

Scott, Worden, and Irwin were granted honorary Doctorates of Astronautical Science from the University of Michigan in 1971.[108] Scott was awarded an honorary doctor of science and technology degree from Jacksonville University in 2013. It was the first honorary degree bestowed by the university.[109]

Scott is a fellow of the American Astronautical Society, an associate fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and a member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, Tau Beta Pi, Sigma Xi, and Sigma Gamma Tau.[16]

In 1982 Scott was inducted with nine other Gemini astronauts into the International Space Hall of Fame in the New Mexico Museum of Space History.[1][110] Along with twelve other Gemini astronauts, Scott was inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in 1993.[88][111]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]

Numbers for Worden/French and for Slayton are Kindle locations.

- ^ a b c d e f g "David R. Scott". New Mexico Museum of Space History. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Mancini, John (May 26, 2018). "Now just four men who walked on the moon are still alive". Quartz. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 12.

- ^ Furlong, William Barry (February 27, 1969). "Flying is in astronaut's blood". Quad-City Times. Davenport, Iowa. World Book Science Service. p. 29. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Brigadier General Tom W. Scott". United States Air Force. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 14–19.

- ^ "Astronauts and the BSA" (PDF). Fact sheet. Boy Scouts of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Scott & Leonov, p. 20.

- ^ "Swimmer Dave Scott: 7th human to walk on the Moon". SwimSwam. April 17, 2020. Archived from the original on April 28, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Simon, Steven (April 4, 2014). "Celebrating the Air Force Academy's 60th anniversary". Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Chaikin, p. 605.

- ^ a b Scott & Leonov, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Astronaut Bio: David R. Scott (Colonel, USAF, Ret.)" (PDF). NASA JSC. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 28.

- ^ "Man in the news: David Randolph Scott". The New York Times. March 4, 1969. p. 15. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.(subscription required)

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 49–50.

- ^ "To the moon, by way of MIT". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. June 3, 2009. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 49–50, 69–75.

- ^ a b French & Burgess, p. 79.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Scott, David (Fall 1982). "The Apollo Guidance Computer: A user's view" (PDF). The Computer Museum Report. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ "David Scott". Caltech. January 2002. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 126, 146–147.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 147.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 79–80.

- ^ French & Burgess, p. 80.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 154.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 83–87.

- ^ "Gemini 8". NASA. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 87–88.

- ^ French & Burgess, p. 88.

- ^ "All Historical Awards" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ a b "Serious Problem in Space". The Times Recorder. Zanesville, Ohio. UPI. March 27, 1966. p. 8. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 183.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 190.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 193–195.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 208.

- ^ Chaikin, pp. 56–59.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 215–217.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 338–339.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 340–341.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 342–343.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 343–352.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 352–353.

- ^ French & Burgess, p. 353.

- ^ Worden & French, 1771.

- ^ Slayton, 4232–4246.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 245–246.

- ^ "Crew of Apollo 13 take last big test". The New York Times. March 27, 1970. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.(subscription required)

- ^ Chaikin, pp. 399–408.

- ^ a b Woods, W. David (1998). "Apollo 15 Flight Summary". NASA. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ Chaikin, p. 412.

- ^ Jones, Eric M., ed. (1996). "Landing at Hadley". Apollo 15 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Eric M., ed. (1996). "Deploying the Lunar Roving Vehicle". Apollo 15 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "Shuttle and Station". Jonathan's Space Report. October 12, 2008. Archived from the original on April 25, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Chaikin, pp. 417–422.

- ^ Chaikin, pp. 437–444.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 319–321, 325–327.

- ^ Faries, p. 28.

- ^ Fletcher July 27, 1972, letter, p. 3.

- ^ Fletcher July 27, 1972, letter, pp. 1, 7–9.

- ^ August 3, 1972, hearing, pp. 107–109.

- ^ Faries, pp. 28–29.

- ^ August 3, 1972, hearing, p. 77.

- ^ August 3, 1972, hearing, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Faries, p. 29.

- ^ Chaikin, p. 497.

- ^ August 3, 1972, hearing, pp. 75–76.

- ^ "U.S. Returns Stamps to Former Astronauts". The New York Times. July 30, 1983. p. 11. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ "Apollo 15 Stamps" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. July 11, 1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ^ Marsh, Al (July 12, 1972). "Astronauts 'Canceled' for 'Stamp Deal'". Today. pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Postmark: The Moon". Newsweek. July 24, 1972. p. 74.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 327.

- ^ August 3, 1972, hearing, pp. 158–160.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. title page, 335–336.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 347–349.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 350.

- ^ Kraft, p. 344.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, p. 380.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, pp. 381–383.

- ^ a b c Boshoff, Alison (May 20, 2000). "Tarnished man from the moon to marry TV's Anna". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Dave Scott – Astronaut Scholarship Foundation". Astronaut Scholarship Foundation. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "Astronaut David Scott ordered to pay $400,000 in fraud case". The Toronto Star. December 30, 1992. p. C8. Retrieved April 26, 2019.(subscription required)

- ^ James, Caryn (April 3, 1998). "Television review; Boyish eyes on the Moon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 6, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (September 7, 2007). "When the Moon was a matter of pride". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ "Space School – Turning actors into astronauts" (PDF). BBC. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ August 3, 1972, hearing, p. 124.

- ^ Dinzeo, Maria (April 4, 2018). "Astronaut's case over Bulova ads cleared for liftoff". Courthouse News Service. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ "Scott v. Citizen Watch Company of America". leagle.com. August 20, 2018. Archived from the original on October 31, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Nick (August 3, 2021). "Bulova's Limited-Edition Lunar Pilot Celebrates the 50th Anniversary of the 'Other' Moon Watch". Esquire.

- ^ Davies, Hugh; Rozenberg, Joshua (July 21, 2001). "Anna Ford's affair with ex-astronaut burns out". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ "List of NASA award recipients" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c "David Randolph Scott". The Hall of Valor Project. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ "Apollo 9 Crew Gets Awards". Florida Today. Cocoa, Florida. Associated Press. March 27, 1969. p. 14A. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Crew of Apollo 15 to get Space Medal". Springfield Leader and Press. Springfield, Missouri. Associated Press. December 8, 1971. p. 17. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wolfe, Sheila (September 16, 1971). "200,000 Welcome Astronauts Here". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thousands Welcome Astronauts in NY". The News. Paterson, New Jersey. UPI. August 25, 1971. p. 28. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Peace Medal Issued By United Nations". Daytona Beach Sunday News-Journal. December 26, 1971. p. 9C. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Wild Blue Yonder Song Really Was". The Orlando Sentinel. Orlando, Florida. Associated Press. September 24, 1971. p. 39. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Haugland, Vern (March 22, 1972). "Apollo 15 astronauts, Gilruth to be honored". El Dorado Times. El Dorado, Arkansas. Associated Press. p. 13. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "FAI Awards". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. October 10, 2017. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ Nawyn, Bert (December 29, 1971). "The World of Stamps". The News. Paterson, New Jersey. p. 18. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Astronaut David Scott, one of 12 to walk on moon, inspires students at Aviation luncheon". The Wave. Jacksonville University. January 30, 2014. Archived from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Shay, Erin (October 3, 1982). "Astronauts Laud Gemini as Precursor to Shuttle". Albuquerque Journal. Albuquerque, New Mexico. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Men Made History during Two Year Project". Florida Today. Cocoa, Florida. March 14, 1993. p. 9E. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

Sources

[edit]- Chaikin, Andrew (1995) [1994]. A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. New York, NY: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-024146-4.

- Faries, Belmont (September 1983). "NASA Returns Moon Covers to the Apollo 15 Astronauts". Society of Philatelic Americans Journal: 27–32. OCLC 815667765.

- Fletcher, James C. (July 27, 1972). "Letter from James C. Fletcher to Clinton P. Anderson". (exhibit to August 3, 1972, committee hearing).(subscription required)

- French, Francis; Burgess, Colin (2010) [2007]. In the Shadow of the Moon. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2979-2.

- Kraft, Christopher (2001). Flight: My Life in Mission Control. New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-94571-0.

- Scott, David; Leonov, Alexei (2006). Two Sides of the Moon: Our Story of the Cold War Space Race (E-Book). with Christine Toomey. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-30866-7.

- Slayton, Deke; Cassutt, Michael (2011) [1994]. Deke! (First E-book ed.). New York: Forge. ISBN 978-1-466-80214-8.

- United States Senate Committee on Aeronautics and Space Sciences (August 3, 1972). "Commercialization of Items Carried by Astronauts". United States Senate.(subscription required)

- Worden, Al; French, Francis (2011). Falling to Earth: An Apollo 15 Astronaut's Journey to the Moon. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1-58834-310-9.

External links

[edit]- David Scott

- 1932 births

- Living people

- Military personnel from San Antonio

- Aviators from Texas

- Apollo 9

- Apollo 15

- Apollo program astronauts

- NASA people

- People who have walked on the Moon

- United States Air Force colonels

- United States Air Force astronauts

- Project Gemini astronauts

- 1966 in spaceflight

- 1969 in spaceflight

- 1971 in spaceflight

- San Antonio Academy alumni

- TMI Episcopal alumni

- MIT School of Engineering alumni

- U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School alumni

- United States Military Academy alumni

- University of Michigan College of Engineering alumni

- United States Astronaut Hall of Fame inductees

- Collier Trophy recipients

- Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the NASA Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the NASA Exceptional Service Medal

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- 20th-century American engineers

- 21st-century American businesspeople

- 21st-century American engineers