Garching

Garching bei München | |

|---|---|

Garching | |

Location of Garching bei München within Munich district  | |

| Coordinates: 48°15′N 11°39′E / 48.250°N 11.650°E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Bavaria |

| Admin. region | Upper Bavaria |

| District | Munich |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–26) | Dietmar Gruchmann (SPD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 28.16 km2 (10.87 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 481 m (1,578 ft) |

| Population (2023-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 17,577 |

| • Density | 620/km2 (1,600/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 85748 |

| Dialling codes | 089 |

| Vehicle registration | M |

| Website | www |

Garching bei München (German: [ˈɡaʁçɪŋ baɪ̯ ˈmʏnçn̩], Garching near Munich) or Garching is a city in Bavaria, near Munich. It is the home of several research institutes and university departments, located at Campus Garching.

History

[edit]Spatial urban planning

[edit]

Garching was small Bavarian village, until the Free State of Bavaria decided to implement a technology and urban planning policy whereby science should be clustered north of Munich. This urban planning policy was in line with the principles advanced by the International Congress of Modernist Architects (CIAM) in the 1933 Athens Charter. Garching was redeveloped in three spatially separated parts, to cover the urban functions of industry, habitation, and research. In 1959 a new residential quarter for Max Planck Society employees was constructed. In 1960 the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics was established in Garching.[2]

In 1963 Technical University of Munich (TUM) published plans, whereby some TUM institutes would be moved to Garching.[3] The Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and the Institute for Radiochemistry were both established in Garching in 1964. In 1966 the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities established the Walther Meißner Institute for Low Temperature Research in Garching. In 1967 the TUM and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU) established a joint accelerator laboratory in Garching. In the same year the TUM moved its department of chemistry and its department of biology to Garching. The industry zone of Garching was built up in Garching-Hochbruck.[4] However, Garching only promoted itself as science city, by incorporating the local nuclear reactor, affectionately known as "atomic egg", in the official coat of arms in 1967.[5]

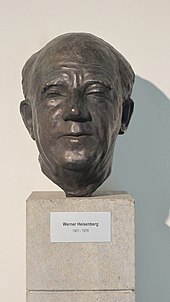

After World War II the scientific publishing business started off slowly and had to be relaunched.[6] A photojournalist lamented, that "photographers would rather go visit the kampas, the dangerous natives on the banks of the Ucayali River, than Professor Heisenberg in the Max Planck Institute."[7]

Districts

[edit]The town has four districts:

- Garching city

- Garching Hochbrück

- Campus Garching (University and Research Campus)

- Dirnismaning

High-tech hub

[edit]Garching is part of the Nordallianz, a group of 8 towns and cities situated north of Munich.

Transport

[edit]The town is at 48°15′N 11°39′E / 48.250°N 11.650°E, near the river Isar and the Bundesautobahn 9.

The Munich U-Bahn line U6 connects the city with the stations Garching-Hochbrück, Garching and Garching-Forschungszentrum (Garching Science Campus).

University and research institutes

[edit]Several research and scientific educational institutions are based in Garching, including:

- Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities

- Technical University of Munich (TUM)

- Institutes of the Max Planck Society (MPG)

- European Southern Observatory (ESO)

- Federal Research Institute for Food Chemistry (Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Lebensmittelchemie DFA)

- Bavarian Center of Applied Energy Research (ZAE)

- General Electric Global Research Center

- BMW M high-performance vehicle research and development

Twin towns

[edit]Garching bei München is twinned with:

Sport

[edit]The town's football club VfR Garching, formed in 1921, experienced its greatest success in 2014 when it won promotion to the Regionalliga Bayern for the first time.

References

[edit]- ^ Genesis Online-Datenbank des Bayerischen Landesamtes für Statistik Tabelle 12411-003r Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes: Gemeinden, Stichtag (Einwohnerzahlen auf Grundlage des Zensus 2011).

- ^ Mikael Hård; Thomas J. Misa, eds. (2008). Urban Machinery: Inside Modern European Cities. Mass. p. 218. ISBN 9780262083690.

- ^ Mikael Hård; Thomas J. Misa, eds. (2008). Urban Machinery: Inside Modern European Cities. Mass. p. 216. ISBN 9780262083690.

- ^ Mikael Hård; Thomas J. Misa, eds. (2008). Urban Machinery: Inside Modern European Cities. Mass. p. 218. ISBN 9780262083690.

- ^ Mikael Hård; Thomas J. Misa, eds. (2008). Urban Machinery: Inside Modern European Cities. Mass. p. 219. ISBN 9780262083690.

- ^ Cathryn Carson (2010). Heisenberg in the Atomic Age: Science and the Public Sphere. Cambridge University Press. p. 137. ISBN 9780521821704.

- ^ Cathryn Carson (2010). Heisenberg in the Atomic Age: Science and the Public Sphere. Cambridge University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9780521821704.