Stockton, California

Stockton | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto: "Stockton: All American City"[3] | |

| Coordinates: 37°58′32″N 121°18′03″W / 37.97556°N 121.30083°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | San Joaquin Valley |

| County | San Joaquin |

| Incorporated | July 23, 1850[4] |

| Named for | Robert F. Stockton |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Manager-Council[5] |

| • Mayor | Kevin J. Lincoln, II (R) |

| • City council | Michele Padilla[6] Daniel Wright[7] Michael Blower[8] Susan Lenz[9] Brando Villapudua[10] Kimberly Warmsley[11] |

| • City manager | Harry E. Black[12] |

| • State senator | Jerry McNerney (D)[13] |

| • Assemblymember | Rhodesia Ransom (D)[13] |

| Area | |

• City | 65.25 sq mi (169.01 km2) |

| • Land | 62.17 sq mi (161.02 km2) |

| • Water | 3.08 sq mi (7.99 km2) 4.76% |

| Elevation | 13 ft (4 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 320,804 |

| • Rank | 1st in San Joaquin County 11th in California 60th in the United States |

| • Density | 4,900/sq mi (1,900/km2) |

| • Urban | 414,847 (US: 101st) |

| • Urban density | 4,486.7/sq mi (1,732.3/km2) |

| • Metro | 779,233 (US: 76th) |

| Demonym | Stocktonian |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | $32.624 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 95201–95213, 95215, 95219, 95267, 95269, 95296–95297 |

| Area code | 209 |

| FIPS code | 06-75000 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1659872, 2411987 |

| Website | www |

Stockton is a city in and the county seat of San Joaquin County in the Central Valley of the U.S. state of California.[19] It is the most populous city in the county, the 11th-most populous city in California and the 60th-most populous city in the United States. Stockton's population in 2020 was 320,804. It was named an All-America City in 1999, 2004, 2015, and again in 2017 and 2018. The city is located on the San Joaquin River in the northern San Joaquin Valley. It lies at the southeastern corner of a large inland river delta that isolates it from other nearby cities such as Sacramento and those of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Stockton was founded by Charles Maria Weber in 1849 after he acquired Rancho Campo de los Franceses. The city is named after Robert F. Stockton,[20] and it was the first community in California to have a name not of Spanish or Native American origin.

Built during the California Gold Rush, Stockton's seaport serves as a gateway to the Central Valley and beyond. It provided easy access for trade and transportation to the southern gold mines. The University of the Pacific (UOP), chartered in 1851, is the oldest university in California, and has been located in Stockton since 1923. In 2012, Stockton filed for what was then the largest municipal bankruptcy in US history – which had multiple causes, including financial mismanagement in the 1990s, generous fringe benefits to unionized city employees,[21] and the 2008 financial crisis. Stockton successfully exited bankruptcy in February 2015.

History

[edit]

When Europeans first arrived in the Stockton area, it was occupied by the Yatchicumne, a branch of the Northern Valley Yokuts Indians. They built their villages on low mounds to keep their homes above regular floods. A Yokuts village named Pasasimas was located on a mound between Edison and Harrison Streets on what is now the Stockton Channel in downtown Stockton.[22]

The Siskiyou Trail began in the northern San Joaquin Valley. It was a centuries-old Native American footpath that led through the Sacramento Valley over the Cascades and into present-day Oregon.[23]

The extensive network of waterways in and around Stockton was fished and navigated by Miwok Indians for centuries. During the California Gold Rush, the San Joaquin River was navigable by ocean-going vessels, making Stockton a natural inland seaport and point of supply and departure for prospective gold-miners. From the mid-19th century onward, Stockton became the region's transportation hub, dealing mainly with agricultural products.

19th century

[edit]

Mexican era

[edit]Carlos Maria Weber was a German émigré in the United States in 1836. He was born as Carl David Weber (February 18, 1814, in Steinwenden – May 4, 1881, in Stockton) and then went by Charles in 1836 in the United States, first spending time in New Orleans and then in Texas. He then came overland from Missouri to California with the Bartleson-Bidwell Party in 1841 and began to go by Carlos, when he began working for John Sutter. In 1842 Weber settled in the Pueblo of San José.

As an alien, Weber could not secure a land grant directly, so he formed a partnership with Guillermo (William) Gulnac. Born in New York, Gulnac had married a Mexican woman and sworn allegiance to Mexico, which then ruled California. He applied in Weber's place for Rancho Campo de los Franceses, a land grant of 11 square leagues on the east side of the San Joaquin River.[24]

Gulnac and Weber dissolved their partnership in 1843. Gulnac's attempts to settle the Rancho Campo de los Franceses failed, and Weber acquired it in 1845. In 1846 Weber had induced a number of settlers to locate on the rancho when the Mexican–American War broke out. Considered a Californio, Weber was offered the position of captain by Mexican general José Castro, which he declined; he later, however, accepted the position of captain in the Cavalry of the United States. Captain Weber's decision to change sides lost him a great deal of the trust he had built up among his Mexican business partners. As a result, he moved to the grant in 1847 and sold his business in San Jose in 1849.

Gold Rush era

[edit]At the start of the California Gold Rush in 1848, Europeans and Americans started to arrive in the area of Weber's rancho on their way to the goldfields. When Weber decided to try his hand at gold mining in late 1848, he soon found selling supplies to gold-seekers was more profitable.[25]

As the head of navigation on the San Joaquin River, the city grew rapidly as a miners' supply point during the Gold Rush. Weber built the first permanent residence in the San Joaquin Valley on a piece of land now known as Weber Point.[22] During the Gold Rush, the location of what is now Stockton developed as a river port, the hub of roads to the gold settlements in the San Joaquin Valley and northern terminus of the Stockton - Los Angeles Road. During its early years, Stockton was known by several names, including "Weberville," "Fat City," "Mudville" and "California's Sunrise Seaport."[2] In 1849 Weber laid out a town, which he named "Tuleburg," but he soon decided on "Stockton" in honor of Commodore Robert F. Stockton. Stockton was the first community in California to have a name that was neither Spanish nor Native American in origin.[1]

Chinese immigration

[edit]Thousands of Chinese came to Stockton from the Guangdong province of China during the 1850s due to a combination of political and economic unrest in China and the discovery of gold in California. After the gold rush, many worked for the railroads and land reclamation projects in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and remained in Stockton. By 1880 Stockton was home to the third-largest Chinese community in California. Discriminatory laws, in particular the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, restricted immigration and prevented the Chinese from buying property.[26] The Lincoln Hotel, built in 1920 by the Wong brothers on South El Dorado Street, was considered one of Stockton's finest hotels of the time. Only after the Magnuson Act was repealed in 1962 were American-born Chinese allowed to buy property and own buildings.[27][28]

Incorporation

[edit]The city was officially incorporated on July 23, 1850, by the county court, and the first city election was held on July 31, 1850. In 1851 the City of Stockton received its charter from the State of California. Early settlers included gold seekers from Asia, Africa, Australia, Europe, the Pacific Islands, Mexico and Canada. The historical population diversity is reflected in Stockton street names, architecture, numerous ethnic festivals and the faces and heritage of a majority of its citizens. In 1870 the Census Bureau reported Stockton's population as 87.6% white and 10.7% Asian. Many Chinese were immigrating to California as workers in these years, especially for the Transcontinental Railroad.[29]

Benjamin Holt settled in Stockton in 1883 and with his three brothers founded the Stockton Wheel Co., and later the Holt Manufacturing Company.

20th century

[edit]

On Thanksgiving Day, November 24, 1904, Holt successfully tested the first workable continuous track tread machine, plowing soggy San Joaquin Valley Delta farmland.[30] Company photographer Charles Clements was reported to have observed that the tractor crawled like a caterpillar, and Holt seized on the metaphor. "Caterpillar it is. That's the name for it."[31]

On April 22, 1918, British Army Col. Ernest Dunlop Swinton visited Stockton while on a tour of the United States. The British and French armies were using many hundreds of Holt tractors to haul heavy guns and supplies during World War I, and Swinton publicly thanked Holt and his workforce for their contribution to the war effort.[32] During 1914 and 1915, Swinton had advocated basing some sort of armored fighting vehicle on Holt's caterpillar tractors, but without success (although Britain did develop tanks, they came from a separate source and were not directly derived from Holt machines).[33] After the appearance of tanks on the battlefield, Holt built a prototype, the gas–electric tank, but it did not enter production.

On January 10, 1920, a major fire on Main Street threatened an entire city block. At about 2 a.m., a blaze was discovered in the basement of the Yost-Dohrmann store, which was gutted, and adjacent businesses were damaged by flames and water. Damage was estimated at $150,000.[34]

By 1931, the Stockton Electric Railroad Co. operated 40 streetcars over 28 miles (45 km) of track.[35]

Stockton is the site of the first Sikh temple in the United States; Gurdwara Sahib Stockton opened on October 24, 1912. It was founded by Baba Jawala Singh and Baba Wasakha Singh, successful Punjabi immigrants who farmed and owned 500 acres (202 ha) on the Holt River.[36]

In 1933, the port was modernized, and the Stockton Deepwater Channel, which improved water passage to San Francisco Bay, was deepened and completed. This created commercial opportunities that fueled the city's growth. Ruff and Ready Island Naval Supply Depot was established, placing Stockton in a strategic position during the Cold War.[37] During the Great Depression the town's canning industry became the battleground of a labor dispute resulting in the Spinach Riot of 1937.[38]

During World War II, the Stockton Assembly Center was built on the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds, a few blocks from what was then the city center. One of 15 temporary detention sites run by the Wartime Civilian Control Administration, the center held some 4,200 Japanese-Americans removed from their West Coast homes under Executive Order 9066, while they waited for transfer to more permanent and isolated camps in the interior of the country. The center opened on May 10, 1942, and operated until October 17, when the majority of its population was sent to Rohwer, Arkansas. The former incarceration site was named a California Historical Landmark in 1980, and in 1984 a marker was erected at the entrance to the fairgrounds.[39]

In 1979, the development of a residential area in Stockton at a burial ground of the tribe unearthed two hundred Miwok remains. In an attempt to prevent the further desecration of the burial grounds, a descendant of the people initiated a legal case which became Wana the Bear v. Community Construction (1982). The decision ultimately sided with the development company, which was heavily criticized by Native Americans as a display of ethnocentrism.[40][41]

In September 1996, the Base Realignment and Closure Commission announced the final closure of Stockton's Naval Reserve Center on Rough and Ready Island. Formerly known as Ruff and Ready Island Naval Supply Depot, the island's facilities had served as a major communications outpost for submarine activities in the Pacific during the Cold War. The site is slowly being redeveloped as commercial property.[42]

Geography

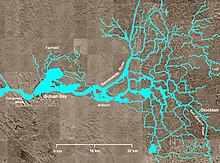

[edit]Stockton is situated amidst the farmland of California's San Joaquin Valley, a subregion of the Central Valley. In and around Stockton are thousands of miles of waterways that make up the California Delta.

Interstate 5 and State Route 99, inland California's major north–south highways, pass through the city. State Route 4 and the dredged San Joaquin River connect the city with the San Francisco Bay Area to its west, creating the Stockton Deepwater Shipping Channel. Stockton and Sacramento are California's only inland sea ports.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city occupies a total area of 64.8 square miles (168 km2), of which 61.7 square miles (160 km2) is land and 3.1 square miles (8.0 km2), comprising 4.76%, is water.

Economy

[edit]

Historically an agricultural community, Stockton's economy has since diversified into other industries, which include telecommunications and manufacturing.

Stockton's central location, relative to San Francisco and Sacramento, its proximity to the state and interstate freeway system, and its comparatively inexpensive land costs have prompted several companies to base their regional operations in the city.

Shopping

[edit]The city of Stockton has one shopping mall, the Weberstown Mall. The city previously housed the Sherwood Mall, adjacent to Weberstown, but in 2022, it was converted into a shopping center now named Sherwood Place. It has the only Dillard's in the Northern California region at the Weberstown Mall, as well as one of the three Sears stores still operating in the Northern California region.

Construction and public spending

[edit]

Beginning in the late 1990s, Stockton had commenced some revitalization projects.[43]

Real estate bubble

[edit]

The Stockton real estate market was disproportionately affected by the 2007 subprime mortgage financial crisis, and the city led the United States in foreclosures for that year, with one of every 30 homes posted for foreclosure.[44] From September 2006 to September 2007, the value of a median-priced house in Stockton declined by 44%.[45]

Stockton's Weston Ranch neighborhood, a subdivision of modest tract homes built in the mid-1990s, had the worst foreclosure rate in the area according to ACORN, a now-defunct national advocacy group for low and moderate-income families.[citation needed] Stockton found itself squarely at the center of the 2000s' speculative housing bubble. Real estate in Stockton more than tripled in value between 1998 and 2005, but when the bubble burst in 2007, the ensuing financial crisis made Stockton one of the hardest-hit cities in United States.[46]

Stockton housing prices fell 39% in the 2008 fiscal year, and the city had the country's highest foreclosure rate (9.5%) as well. Stockton also had an unemployment rate of 13.3% in 2008, one of the highest in the United States. Stockton was rated by Forbes in 2009 as America's fifth most dangerous city because of its crime rate.[46] In 2010, mainly due to the aforementioned factors, Forbes named it one of the three worst places to live in the United States.[47]

City bankruptcy

[edit]Following the 2008 financial crisis, in June 2012 Stockton became the largest city in U.S. history to file for bankruptcy protection. It was surpassed by Detroit in July 2013. The city approved a plan to exit bankruptcy in October 2013,[48] and voters approved a sales tax on November 5, 2013, to help fund the exit.[49]

The collapse in real estate valuations had a negative effect on the city's revenue base. On June 28, 2012, Stockton filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy.[50] On April 1, 2013, the United States Bankruptcy Court Eastern District of California ruled that Stockton was eligible for bankruptcy protection.

The Stockton bankruptcy case lasted longer than two years and received nationwide attention. On October 4, 2013, Stockton City Council approved a bankruptcy exit plan by a 6–0 vote[48] to be filed with the U.S. Bankruptcy Court, Eastern District of California, Sacramento. Voters approved a 3⁄4-cent sales tax on November 5, 2013, to help fund the bankruptcy exit.[49]

On October 30, 2014, a federal bankruptcy judge approved the city's bankruptcy recovery plan, thus allowing the city to continue with the planned pension payments to retired workers.[51] The city exited from Chapter 9 bankruptcy on February 25, 2015.

Experiment in Guaranteed Basic Income

[edit]As part of a privately funded experiment in Universal Basic Income in 2019, the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (S.E.E.D.) conducted a pilot project that gave a $500 stipend to 125 randomly selected residents for an 24-month period with “no strings attached."[52] It was made possible by the Economic Security Project,[53] an advocacy group chaired by Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes, which provided the first $1 million for the program, and a dozen other Silicon Valley organizations and private donors who funded the rest of its $3 million budget.[54][55] The positive benefits of the program during the first year were described in an interim report published in March 2021.[56]

Climate

[edit]

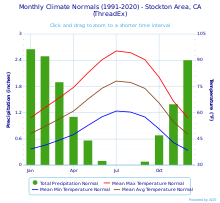

Stockton's climate lies right on the boundary of, and fluctuates between, hot-summer Mediterranean (Köppen: Csa) and cool semi-arid (BSk). Stockton is characterized by very hot, arid summer and cool, wet winter. In an average year, nearly 95% of the 13.45 inches (341.6 mm) of precipitation falls from October through April.[57] Located in the Central Valley, the temperature range is much greater than in the nearby Bay Area. The degree of diurnal temperature variation is roughly twice as high in the summer as in the winter. Tule fog blankets the area during some winter days. Stockton lies in the fertile heart of the California Mediterranean climate prairie delta, about equidistant from the Pacific Ocean and the Sierra Nevada.[citation needed] The intermediate climate between the coast and the Central Valley gives a similar climate to that of Badajoz, Spain.[58]

At the airport, the highest recorded temperature was 115 °F (46 °C) on July 23, 2006, and September 6, 2022, and the lowest was 16 °F (−9 °C) on January 11, 1949. There are an average of 88 afternoons annually with high temperatures of 90 °F (32.2 °C) or higher, and 19 afternoons of 100 °F (37.8 °C) or above; 19 mornings see low temperatures at or below freezing. The wettest "rain year" was from July 1982 to June 1983 with 27.89 inches (708.4 mm) and the driest from July 1975 to June 1976 with 5.71 inches (145.0 mm).[59] Note that regional difference of precipitation has been recorded in Stockton. The more northern part of Stockton receives more precipitation than southern Stockton.

The most rainfall in one month was 8.22 inches (208.8 mm) in February 1998 and the most rainfall in 24 hours was 3.01 inches (76.5 mm) on January 21, 1967.[59] There are an average of 56.5 days with measurable precipitation.[57] Only light amounts of snow have been recorded, and the only instance of measurable snowfall occurred on February 5, 1976, with 0.3 in (0.8 cm) measured.[59]

A 2018 federal study predicts that flooding of the San Joaquin River could possibly cause much of Stockton to become submerged beneath 10–12 feet of water, causing a humanitarian disaster as costly and deadly as Hurricane Katrina if the levees are not upgraded.[60][61]

| Climate data for Stockton Metropolitan Airport, California (1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1948–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

79 (26) |

87 (31) |

100 (38) |

107 (42) |

111 (44) |

115 (46) |

113 (45) |

115 (46) |

105 (41) |

85 (29) |

76 (24) |

115 (46) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 65.3 (18.5) |

71.6 (22.0) |

79.3 (26.3) |

89.3 (31.8) |

97.3 (36.3) |

104.3 (40.2) |

105.8 (41.0) |

104.9 (40.5) |

101.4 (38.6) |

92.2 (33.4) |

77.8 (25.4) |

65.9 (18.8) |

107.7 (42.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 57.0 (13.9) |

62.9 (17.2) |

68.5 (20.3) |

74.5 (23.6) |

82.8 (28.2) |

90.4 (32.4) |

95.4 (35.2) |

94.4 (34.7) |

90.4 (32.4) |

80.3 (26.8) |

66.6 (19.2) |

57.1 (13.9) |

76.7 (24.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 48.0 (8.9) |

52.1 (11.2) |

56.4 (13.6) |

60.9 (16.1) |

67.7 (19.8) |

74.0 (23.3) |

78.1 (25.6) |

77.3 (25.2) |

73.9 (23.3) |

65.5 (18.6) |

54.7 (12.6) |

47.7 (8.7) |

63.0 (17.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 39.1 (3.9) |

41.3 (5.2) |

44.2 (6.8) |

47.4 (8.6) |

52.6 (11.4) |

57.6 (14.2) |

60.9 (16.1) |

60.3 (15.7) |

57.5 (14.2) |

50.6 (10.3) |

42.8 (6.0) |

38.4 (3.6) |

49.4 (9.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 28.2 (−2.1) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

35.0 (1.7) |

38.3 (3.5) |

44.5 (6.9) |

49.8 (9.9) |

54.1 (12.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

49.9 (9.9) |

41.0 (5.0) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 16 (−9) |

13 (−11) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

29 (−2) |

35 (2) |

38 (3) |

37 (3) |

32 (0) |

26 (−3) |

23 (−5) |

15 (−9) |

13 (−11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.27 (83) |

2.80 (71) |

2.31 (59) |

1.11 (28) |

0.57 (14) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.01 (0.25) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.69 (18) |

1.05 (27) |

2.81 (71) |

14.8 (375.75) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.7 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 5.3 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 6.4 | 9.1 | 56.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83.6 | 78.1 | 69.5 | 61.4 | 52.9 | 48.6 | 46.4 | 48.2 | 52.0 | 59.8 | 75.5 | 83.6 | 63.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 39.6 (4.2) |

42.3 (5.7) |

42.1 (5.6) |

42.3 (5.7) |

45.7 (7.6) |

48.9 (9.4) |

51.8 (11.0) |

52.0 (11.1) |

50.5 (10.3) |

46.9 (8.3) |

43.9 (6.6) |

39.2 (4.0) |

45.4 (7.5) |

| Source: NOAA (dew points and relative humidity 1961–1990)[59][57][62] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 3,679 | — | |

| 1870 | 10,066 | 173.6% | |

| 1880 | 10,282 | 2.1% | |

| 1890 | 14,424 | 40.3% | |

| 1900 | 17,506 | 21.4% | |

| 1910 | 23,253 | 32.8% | |

| 1920 | 40,296 | 73.3% | |

| 1930 | 47,963 | 19.0% | |

| 1940 | 54,714 | 14.1% | |

| 1950 | 70,853 | 29.5% | |

| 1960 | 86,321 | 21.8% | |

| 1970 | 109,963 | 27.4% | |

| 1980 | 148,283 | 34.8% | |

| 1990 | 210,943 | 42.3% | |

| 2000 | 243,771 | 15.6% | |

| 2010 | 291,707 | 19.7% | |

| 2020 | 320,804 | 10.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[63][failed verification] 2020[16] | |||

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Newer information is available from the 2020 census report. (February 2022) |

| Historical racial composition | 2010[64] | 1990[65] | 1970[65] | 1940[65] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 37.0% | 57.5% | 79.5% | 90.7% |

| —Non-Hispanic whites | 22.1% | 43.6% | 63.3%[b] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 12.2% | 9.6% | 11.0% | 1.6% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 40.3% | 25.0% | 17.5%[b] | n/a |

| Asian | 21.5% | 22.8% | 7.9% | 7.6% |

2020

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[66] | Pop 2010[67] | Pop 2020[68] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 78,539 | 66,836 | 54,765 | 32.22% | 22.91% | 17.07% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 26,359 | 33,507 | 38,178 | 10.81% | 11.49% | 11.90% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 1,337 | 1,237 | 1,237 | 0.55% | 0.42% | 0.39% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 47,093 | 60,323 | 67,738 | 19.32% | 20.68% | 21.12% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 810 | 1,622 | 2,440 | 0.33% | 0.56% | 0.76% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 496 | 470 | 1,608 | 0.20% | 0.16% | 0.50% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 9,920 | 10,122 | 13,237 | 4.07% | 3.47% | 4.13% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 79,217 | 117,590 | 141,601 | 32.50% | 40.31% | 44.14% |

| Total | 243,771 | 291,707 | 320,804 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 US Census

[edit]The 2010 United States Census[69] reported that Stockton had a population of 291,707. The population density was 4,505.0 inhabitants per square mile (1,739.4/km2). The racial makeup of Stockton was 108,044 (37.0%) white (22.1% non-Hispanic white[64]), 35,548 (12.2%) African American, 3,086 (1.1%) Native American, 62,716 (21.5%) Asian (7.2% Filipino, 3.5% Cambodian, 2.1% Vietnamese, 2.0% Hmong, 1.8% Chinese, 1.6% Indian, 1.0% Laotian, 0.6% Pakistani, 0.5% Japanese, 0.2% Korean, 0.1% Thai), 1,822 (0.6%) Pacific Islander (0.2% Samoan, 0.1% Tongan, 0.1% Guamanian), 60,332 (20.7%) from other races, and 20,159 (6.9%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 117,590 persons (40.3%). 35.7% of Stockton's population was of Mexican descent, and 0.6% Puerto Rican.

The 2010 census reported that 285,973 people (98.0% of the population) lived in households, 3,896 (1.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 1,838 (0.6%) were institutionalized.

There were 90,605 households, out of which 41,033 (45.3%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 41,481 (45.8%) were heterosexual married couples living together, 17,140 (18.9%) had a female householder with no husband present, 7,157 (7.9%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 7,123 (7.9%) unmarried heterosexual partnerships, and 720 (0.8%) same-sex married or registered domestic partnerships. 19,484 households (21.5%) were made up of individuals, and 7,185 (7.9%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.16. There were 65,778 families (72.6% of all households); the average family size was 3.69.

The population was spread out, with 87,338 people (29.9%) under the age of 18, 34,126 people (11.7%) aged 18 to 24, 76,691 people (26.3%) aged 25 to 44, 64,300 people (22.0%) aged 45 to 64, and 29,252 people (10.0%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.5 males.

There were 99,637 housing units at an average density of 1,538.7 units per square mile (594.1 units/km2), of which 46,738 (51.6%) were owner-occupied, and 43,867 (48.4%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 3.2%; the rental vacancy rate was 9.4%. 146,235 people (50.1% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 139,738 people (47.9%) lived in rental housing units.

Rankings

[edit]- In 2020, U.S. News & World Report named Stockton as America's most diverse city.[70]

Due to a number of socio-economic problems, Stockton has been subject to a series of negative national rankings:

- In a 2010 Gallup poll, Stockton was tied with Montgomery, Alabama for the most obese metro area in the US with an obesity rate of 34.6 percent.[71]

- In the February 2012 issue of Forbes, the magazine ranked Stockton the eighth most miserable US city, largely as a result of the steep drop in home values and high unemployment.[45]

- In 2012 the National Insurance Crime Bureau ranked Stockton seventh in auto theft rate per capita in the US.[72]

- In 2012, Stockton was ranked as the tenth most dangerous city in America and the second most dangerous in California (behind Oakland).[73]

- In 2013, Stockton was ranked as the third least literate city in the U.S. in a study by Central Connecticut State University, with less than 17% of adults holding a college degree,[74] and ABC.com ranked the city as the third least literate of all U.S. cities with a population of more than 250,000 behind Bakersfield, California, and Corpus Christi, Texas.[75]

Top employers

[edit]According to the city's 2022 comprehensive annual financial report,[76] the top employers in the city were:[c]

| No. | Employer | No. of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stockton Unified School District | 5,265 |

| 2 | Amazon | 4,750 |

| 3 | St. Joseph's Medical Center | 3,200 |

| 4 | City of Stockton | 2,118 |

| 5 | San Joaquin County Office of Education | 1,955 |

| 6 | Pacific Gas and Electric | 1,550 |

| 7 | University of the Pacific | 1,329 |

| 8 | Lincoln Unified School District | 1,125 |

| 9 | Kaiser Permanente | 1,065 |

| 10 | San Joaquin Delta College | 813 |

Arts and culture

[edit]Performing arts

[edit]

Music

[edit]- Stockton Symphony is the third-oldest professional orchestra in California (founded in 1926), after the San Francisco Symphony and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.[77]

- University of the Pacific is known for its music conservatory and for being the home of the Brubeck Institute, named after Dave Brubeck, a Pacific alumnus and jazz piano legend. The institute maintains an archive of Brubeck's work and offers a fellowship program for young musicians. The Brubeck Institute Jazz Quartet is composed of Pacific students and tours widely.[78]

- San Joaquin Delta College has a growing jazz program and is home to several official and unofficial jazz bands composed of Delta and Pacific students and faculty.[79]

- Christian Life College offers associate and Bachelor of Arts degrees in Christian music.

Stockton hosts several live-music venues, including:

- Stockton Arena, which is home to several sports teams, and has hosted nationally known entertainers such as Gwen Stefani, Rob Zombie, Ozzy Osbourne, Josh Groban, Carrie Underwood and Bob Dylan.

- The annual Apollo Night talent show draws about 1,500 people to the Stockton Memorial Civic Auditorium (1925) to watch performances by aspiring Northern California musicians.[80]

Theatre

[edit]The Bob Hope Theatre in downtown Stockton, formerly known as the Fox California Theatre, built in 1930,[81] is one of several movie palaces in the Central Valley. Bob Hope often came to Stockton to visit close friend and billionaire tycoon Alex Spanos, who donated much of the money to revitalize the theater after Hope's death. The University of the Pacific Faye Spanos Concert Hall often hosts public performances, as does the Stockton Memorial Civic Auditorium. The Warren Atherton Auditorium at the Delta Center for the Arts on the campus of the San Joaquin Delta College is a 1,456-seat theater with a 60-foot (18 m) proscenium and full grid system.[82] The Stockton Empire Theater is an art deco movie theater that has been revitalized as a venue for live music.

Founded in 1951, the Stockton Civic Theatre offers an annual series of musicals, comedies and dramas. It maintains a 300-seat theater in the Venetian Bridges neighborhood. The company also hosts the annual Willie awards for the local performing arts.

Other performing arts organizations and venues include the Stockton Opera[83] and others.

Visual arts

[edit]Museums and galleries

[edit]Stockton is home to several museums:

- Haggin Museum — the private, non-profit fine arts and history museum was built in Victory Park in 1931. The museum displays 19th and 20th-century works of art and houses local historical exhibits. The Haggin Museum features collections and exhibits related to local Valley history and California history. The museum also displays fine art of late 19th and early 20th century artists such as Jean Béraud, Albert Bierstadt, Rosa Bonheur, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Paul Gauguin, Jean-Léon Gérôme, Childe Hassam, George Inness, Daniel Ridgway Knight, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Jehan-Georges Vibert, and Jules Worms.[22]

- The San Joaquin County Historical Society and Museum operates an 18-acre (7.3 ha) museum facility at Micke Grove Regional Park, two miles (3.2 km) north of the city. The museum houses exhibits dedicated to the founding of Stockton, San Joaquin County's legacy of innovation in agriculture and manufacturing, immigrant communities in Stockton and Lodi, and historic industries in San Joaquin County.

- Reynolds Gallery, and Horton Gallery — the University of the Pacific Reynolds Gallery, and the San Joaquin Delta College Horton Gallery, both feature contemporary work by students and local and nationally known artists.

- Children's Museum of Stockton — housed in a former warehouse in the Downtown Waterfront District, featuring many interactive displays.

- Elsie May Goodwin Gallery — operated by the Stockton Art League.

- Filipino American National Historical Society proposed the construction of the National Pinoy Museum in the Little Manila district, dedicated to the history of Filipino Americans. Stockton historically had one of the largest populations of Filipinos, immigrants and U.S. citizens, in the United States.[84] The museum opened in 2015 after two decades of planning.[85][86]

- Art Expressions of San Joaquin – an artists' cooperative featuring the works of local artists – with a prior gallery on the Miracle Mile and ongoing shows at the Hilton Hotel, the County Administration Building and the Stockton Metropolitan Airport.

- Stockton Field Aviation Museum – sponsored by the Aeronautical Education Foundation, featuring WWII-era memorabilia.

Murals depicting the city's history decorate the exteriors of many downtown buildings.

- Mexican Heritage Center & Gallery, Inc. — A non-profit located in downtown Stockton whose mission is to educate and promote art and culture for current and future generations. Since the late 1990s, the Mexican Heritage Center & Gallery has been a pioneer in bringing Mexican visual and performing arts to the Stockton community.

With over 77,000 trees, the City of Stockton has been labeled Tree City USA some 30 times.[22]

Stockton has over 275 restaurants, ranging in variety reflective of the population demographics. A mix of American, African American, BBQ, Cambodian, Chinese, Filipino, Greek, Italian, Mexican and Vietnamese restaurants are abundant in the community reflecting the city's diverse culture. Cantonese restaurant On Lock Sam still exists and dates back to 1895.[87]

Festivals

[edit]Stockton hosts many annual festivals celebrating the cultural heritage of the city, including:

- San Joaquin Children's Film Festival

- San Joaquin International Film Festival (February)[88]

- Chinese New Year's Parade and Festival (First Sunday in March)

- St. Patrick's Day and Shamrock Run (March)

- Great Stockton Asparagus Dine Out (April)

- Stockton Asparagus Festival — annual Asparagus food festival (April)[89]

- Brubeck Jazz Festival (April)[90]

- Earth Day Festival (April)

- Cambodian New Year (April)

- Annual Nagar Kirtan, Sikh parade (April)[91]

- Boat Parade for the Opening of Yachting Season (April)

- Stockton Flavor Fest (May)

- Cinco de Mayo Parade and Festival (May)

- Zion Academy's Reclaim (May)

- Jewish Food Fair (June)

- Juneteenth Day Celebration (June)

- Stockton Obon Bazaar (July)[92]

- Peruvian Independence Day Festival (July)

- Taste of San Joaquin and West Coast BBQ Championships

- Filipino Barrio Fiesta (August)[93]

- Stockton Beer Week (August)[94]

- Stockton Pride (August)

- Christian Spirit Festival (September)

- The Record's Family Day at the Park (Sept)

- Stockton Restaurant Week (September)

- Black Family Day (September)

- San Joaquin County Coastal Cleanup Day (September)

- Greek Festival (September) First weekend after Labor Day

- Festa Italiana: Tutti In Piazza (September)

- Stocktoberfest, Beer and Brats Festival on the Waterfront (October)

- Dia De Los Muertos Festival (October)[95]

- Hmong New Year (November)

- Stockton Festival of Lights and Boat Parade (December)

Sports

[edit]Stockton is home to two minor league franchises:

- Stockton Kings—(NBA G League basketball team; affiliate of the Sacramento Kings)

- Stockton Ports—(Low-A West baseball team; affiliate of the Athletics)

- Team Trouble—(ABA basketball team)

The Stockton Ports Baseball Team play their home games at Banner Island Ballpark, a 5,000-seat facility built for the team in downtown Stockton. The Ports played their home games at Billy Hebert Field from 1953 to 2004. The Ports have been a single A team in Stockton since 1946 in the California Minor Leagues. Stockton has minor league baseball dating back to 1886.[96] The Ports have produced 244 Major League players including Gary Sheffield, Dan Plesac, Doug Jones, Pat Listach, and Stockton's own Dallas Braden among others.[97] The Ports have eleven championships and are currently the A class team for the Athletics. The Ports had the best win–loss percentage in all Minor League Baseball in the 1980s.[98]

A 10,000-seat arena, Stockton Arena, located in Downtown Stockton, opened in December 2005 and is home to the Stockton Kings (NBAGL)

Stockton is home to the oldest NASCAR-certified race track West of the Mississippi. The Stockton 99 Speedway opened in 1947 and is a quarter-mile oval paved track with grandstands that can accommodate 5,000 spectators.[citation needed]

Stockton's designation for Little League Baseball is District 8, which has 12 leagues of teams within the city. Stockton also has several softball leagues including Stockton Girls Softball Association, and Port City Softball League, each having several hundred members.[citation needed]

Rowing Regatta featuring Junior, Collegiate and Master Level Rowing & Sculling Competition is organized by the University of the Pacific[99] annually on the Stockton's Deep Water Channel. Teams from throughout Northern California compete in this Olympic sport which is also the oldest collegiate sport in the United States.

Stockton hosts a wide variety of sports events every year: from resident hockey, baseball and soccer games through basketball at the University of the Pacific and at the Stockton Arena; golf championships at two 18-hole courses and a Par 3 Executive Course; rowing, sailing and fishing on the Delta and the Stockton Channel; martial arts and cage fighting. There are four public golf courses open year-round, Van Buskirk, Swenson, and The Reserve at Spanos Park and Elkhorn Golf Course. Private courses include The Stockton Golf & Country Club, Oakmoore, and Brookside Golf & Country Club.[citation needed]

Stockton is one of a handful of cities that lays claim to being the inspiration for the 1888 poem "Casey at the Bat."[100] The University of the Pacific was the summer home of the San Francisco 49ers Summer Training Camp from 1998 through 2002.

Stockton is also the base of UFC fighters Nick and Nate Diaz. Nick is the former WEC and Strikeforce Welterweight champion,[101] while Nate is the winner of The Ultimate Fighter 5.[102] Both brothers are Brazilian jiu-jitsu black belts under Cesar Gracie[103] and operate a school in Stockton which teaches Brazilian jiu-jitsu to children and youth.[104][105]

Parks and recreation

[edit]

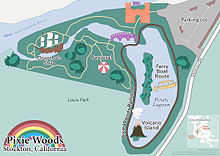

The City of Stockton has a small children's amusement park, Pixie Woods; the park opened in 1954 and has since welcomed more than one million visitors.[106]

Government

[edit]On November 3, 2020, Kevin J. Lincoln II was elected mayor, defeating incumbent mayor Michael Tubbs. He assumed office on January 1, 2021.[107]

- City council

The City Council consists of the following members as of January 1, 2021:[108]

- Kevin Lincoln— Mayor

- Sol Jobrack— District 1

- Dan Wright— District 2

- Paul Canepa— District 3

- Susan Lenz— District 4

- Christina Fugazi— District 5

- Kimberly Warmsley— District 6

The current form of government is a city manager council.[109]

Stockton is also seat of San Joaquin County, for which the government of San Joaquin County is defined and authorized under the California Constitution and law as a general law county. The county government provides countywide services such as elections and voter registration, law enforcement, jails, vital records, property records, tax collection, public health, and social services. The county government is primarily composed of the elected five-member Board of Supervisors and other elected offices including the Sheriff, District Attorney, and Assessor, and numerous county departments and entities under the supervision of the county administrator.[110]

Police department

[edit]

- Cleveland Elementary School shooting

On January 17, 1989, the Stockton Police Department received a threat against Cleveland Elementary School from an unknown person. Later that day, Patrick Purdy, who was later found to be mentally ill, opened fire on the school's playground with a semi-automatic rifle, killing five children, all Cambodian or Vietnamese refugees, and wounding 29 others, and a teacher, before taking his own life. The Cleveland Elementary School shooting received national news coverage and is sometimes referred to as the Cleveland School massacre.[111]

- Budget crisis

The city cut its police force by more than 20% during the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, but voters approved a sales tax on November 5, 2013, that provided funds to hire an additional 120 police officers.[112][113]

- Bank robbery

On July 16, 2014, officers responded to an armed bank robbery, which resulted in the four perpetrators taking three hostages and leading them on an hour-long high-speed pursuit. Over the course of the car chase, one suspect fired over 100 rounds from an AK-47s at police, disabling 14 police vehicles, including the department's own Lenco BearCat armored personnel carrier. More than 30 officers shot over 600 rounds into the getaway vehicle. Two perpetrators were killed, two hostages were injured, one hostage was killed by police ammunition, and numerous vehicles and other property were damaged or destroyed by the nearly 1,000 rounds of ammunition fired by the robbers and police.[114] The department faced criticism with its handling of the incident in the aftermath.[115]

- Crime

In 2012, the City of Stockton was the 10th[73] most dangerous city in America, reporting 1,417 violent crimes per 100,000 persons, well above the national average, and 22 murders per 100,000 (above the average of 4.7).[citation needed] In 2013, violent crime lessened to 1,230.3 crimes per 100,000 population, making it 19th on the list of the most dangerous cities.[116] Stockton has experienced a high rate of violent crime, reaching a record high of 71 homicides in 2012 before dropping to 32 for all of 2013.[116][117]

Stockton Police Chief Eric Jones credited 2013's drop in the murder rate to Operation Ceasefire, a gun violence intervention strategy pioneered in Boston and implemented in Stockton in 2012,[118] combined with a federal gun and narcotics operation.[119]

Fire department

[edit]The Stockton Fire Department was first rated as a Class 1 fire department by the Insurance Services Office in 1971. In 2005, all 13 of the city's stations met the National Fire Protection Association standard of a 5-minute response time.[120] In 2009, it had 13 fire stations and over 275 career personnel.[121] Due in part to staffing levels that placed five staff on ladder companies and four staff on engines, it was one of only 57 departments among 44,000 to receive the Class 1 rating in 2010.[122]

The department maintained this rating until 2011, when during the city's Chapter 9 bankruptcy proceedings and following a Civil Grand Jury investigation, the city reduced staffing levels from 220 full-time staff to 177, and the 2011 budget from $59 million to $40 million. The department was cut by 30%.[123] The bankruptcy was due in part to a 1996 decision made by the city to provide firefighters with free health care after retirement, which they later expanded to all city employees. The benefit gradually grew into a $417 million liability.[124]

As of 2016[update], the department consists of 12 firehouses that house 12 Engine Companies and three Truck Companies. In 2015 the Fire Department responded to over 40,000 emergency calls for service, including more than 300 working structure fires. The department is one of the busiest in the United States. The Stockton Fire Department is assisted on medical emergency calls by American Medical Response.[125]

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary

[edit]

Stockton is part of four public school districts: Stockton Unified School District, Lincoln Unified School District, Lodi Unified School District, and Manteca Unified School District. There are more than 40 private elementary and secondary schools, including Saint Mary's High School. Stockton is also home to public charter school systems including Aspire Public Schools, Stockton Collegiate, Stockton Unified Early College Academy, and Venture Academy.[citation needed]

Post-secondary

[edit]The University of the Pacific moved to Stockton in 1923 from San Jose. The university is the only private school in the United States with less than 10,000 students enrolled that offers eight different professional schools. It also offers a large number of degree programs relative to its student population.[126] The men's Pacific Tigers basketball team has been in the NCAA Tournament nine times. The Tigers have played their home games at the Alex G. Spanos Center since 1982, prior to that playing at the Stockton Memorial Civic Auditorium since 1952. The campus has been used in the filming of a number of Hollywood films (see below), partly due to its likeness to East Coast Ivy League universities.[127]

Also located in Stockton are:

- San Joaquin Delta College, which serves a district area that includes all of San Joaquin County and parts of Alameda, Calaveras, Sacramento, and Solano counties.[128]

- California State University, Stanislaus established a Stockton campus on the grounds of the former Stockton State Hospital. The hospital was the first state mental institution in California;

- Humphreys University, a private non-profit institution offering undergraduate and graduate degrees including a Juris Doctor from the Laurence Drivon School of Law

- Kaplan College of Stockton

- Christian Life College, a private four-year Bible college offering associate and Bachelor of Arts degrees in Bible and theology or Christian music

- MTI Business College

- UEI College

Transportation

[edit]Stockton is centrally located with access to:

- Port of Stockton — an international deep-water port

- Amtrak railroad system

- Intrastate and Interstate freeway systems

- Stockton Metropolitan Airport

Roads and railways

[edit]

Due to its location at the "crossroads" of the Central Valley and a relatively extensive highway system, Stockton is easily accessible from virtually anywhere in California. Interstate 5 and State Route 99, California's major north–south thoroughfares, pass through the city limits. The east–west highway State Route 4 also passes through the city, providing access to the San Francisco Bay Area as well as the Sierra Nevada and its foothills. Stockton is the western terminus of State Route 26 and State Route 88, which extends to the Nevada border. In addition, Stockton is within an hour of Interstate 80, Interstate 205 and Interstate 580.[citation needed]

Stockton is served by San Joaquin Regional Transit District.[129]

Stockton is also connected to the rest of the nation through a network of railways. Stockton has two passenger rail stations. Robert J. Cabral Station, which provides service to Sacramento on Amtrak's San Joaquins route, and also serves as the northern terminus of the Altamont Corridor Express commuter rail service to San Jose. San Joaquin Street station provides service to Oakland via the San Joaquins route.

Union Pacific and BNSF Railway, the two largest railroad networks in North America both service Stockton and its port via connections with the Stockton Terminal and Eastern Railroad and Central California Traction Company, who provide local and interconnecting services between the various rail lines. The Stockton Diamond was the busiest interchange point in the state by 2020;[130] a grade separation project to elevate the Union Pacific over the BNSF line is planned to be completed by 2026.

Air

[edit]

Stockton is served by Stockton Metropolitan Airport, located on county land just south of city limits. The airport has been designated a Foreign Trade Zone and is mainly used by manufacturing and agricultural companies for shipping purposes. Since airline deregulation, passenger service has come and gone several times. Domestic service resumed on June 16, 2006, with service to Las Vegas by Allegiant Air.[131] The days of service and number of flights were expanded a few months later due to demand. Air service to Phoenix began in September 2007.

On July 1, 2010, Allegiant Air implemented non-stop service to and from Long Beach.[131] In 2006 Aeromexico had plans to provide flights to and from Guadalajara, Mexico, but the airport's plan to build a customs station at the airport was initially rejected by the customs service. However, the possibility of building this station is currently a continuing matter of negotiation between the airport and the customs service, and Aeromexico has indicated a continuing interest in eventually providing service. Ground transportation is available from Hertz, Enterprise, Yellow Cab and Aurora Limousine.[citation needed]

Seaport

[edit]The Port of Stockton is a fully operating seaport approximately 75 nautical miles (86 mi; 139 km) east of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. Set on the San Joaquin River, the port operates a 4,200-acre (17 km2)[132] transportation center with berthing space for 17 vessels up to 900 feet (270 m) in length.[133] As of 2014, the Port of Stockton had 136 tenants[134] and is served by BNSF & UP Railroads.[135] The port also includes 1.1 million square feet (100,000 m2) of dockside transit sheds and shipside rail track and 7.7 million square feet (720,000 m2) of warehousing.[136]

Adjacent to the port is Rough and Ready Island, which served as a World War II–era naval supply base until it was decommissioned during the Base Realignment and Closure process in 1995.

Media

[edit]Periodicals

[edit]- Daily periodicals

- The Record is a daily newspaper

- Stocktonia News Service is an online news site for Stockton.

- Weekly periodicals

- Bilingual Weekly News publishes a weekly newspaper, in both Spanish and English

- Monthly periodicals

- Artifact is a San Joaquin Delta College periodical based in Stockton from December 2006 - 2020. Writing in all genres, photography and visual media by students, staff and faculty as well as community members are accepted.

- Caravan is a local community arts and events monthly tabloid.

- Poets' Espresso Review is a periodical that was based in Stockton and was mostly distributed by mail from 2005 to 2010.

- San Joaquin Magazine is a regional lifestyle magazine covering Stockton, Lodi, Tracy, and Manteca.

- The Central Valley Business Journal is a monthly business tabloid.

- The Downtowner was a free monthly guide to downtown Stockton's events, commerce, real estate, and other cultural and community happenings.

Radio broadcast stations

[edit]AM stations

[edit]- KCVR 1570: Spanish Adult Hits

- KWG 1230: Catholic, switched formats to News/talk. Established in 1921, one of California's oldest running AM radio stations.[137]

- KWSX 1280: Rock and Roll simulcast of KMRQ 96.7 Riverbank

- KSTN 1420 Modern Country Simulcast on 105.9FM

In addition, several radio stations from nearby San Francisco, Sacramento and Modesto are receivable in Stockton.

FM stations

[edit]- KQED-FM 88.5: (NPR affiliate) News/Talk

- KLOVE 89.7: Christian

- KYCC 90.1: Christian

- KUOP 91.3: (Capital Public Radio) (NPR affiliate) News/Talk and Jazz

- KWDC LP 93.5: (NPR) News/Talk and Music Varieties

- KHOP 95.1: Top 40

- KWIN 97.7: Urban Contemporary

- KRXQ 98.5: Alternative Rock

- KJOY 99.3: Lite Rock

- KQOD 100.1: Rhythmic Oldies

- KMIX 100.9: Regional Mexican

- KATM 103.3: Country

- KELR-LP 104.7: (3ABN Radio) Christian

- The Hawk 104.1: Classic Rock

- KSTN 105.9 Modern Country

- KLVS 107.3: Christian

Television stations

[edit]As part of the Sacramento-Stockton-Modesto television market, Stockton is primarily served by stations based in Sacramento, but may carry some San Francisco Bay area television stations' airwaves. These are listed below, with the city of license in bold:

- KCRA Channel 3 (NBC affiliate) Sacramento

- KRON Channel 4 (The CW O&O) San Francisco

- KVIE Channel 6 (PBS member station) Sacramento

- KQED Channel 9 (PBS member station) San Francisco

- KXTV Channel 10 (ABC affiliate) Sacramento

- KOVR Channel 13 (CBS O&O) Stockton

- KUVS Channel 19 (Univision O&O) Modesto

- KSPX-TV Channel 29 (Ion O&O) Sacramento

- KMAX Channel 31 (Independent station) Sacramento

- KCSO-LD Channel 33 (Telemundo O&O) Sacramento

- KTXL Channel 40 (Fox affiliate) Sacramento

- KTNC Channel 42 (Tri-State Christian Television O&O) Concord

- KQCA Channel 58 (dual affiliate of The CW and MyNetworkTV) Sacramento

- KTFK-DT Channel 64 (UniMás O&O) Stockton

In popular culture

[edit]Comics

[edit]- Stan Lee named Stockton as the birthplace of the Fantastic Four in 1986, after Joe Field successfully petitioned Marvel Comics to change it from the fictional "Central City".[138]

Films

[edit]A number of motion pictures have been filmed in Stockton, including:

- All the King's Men (1949)[139]

- The Big Country (1958)[139]

- Bird[140]

- Big Stan (2007)[141]

- Blood Alley (1955)[139]

- Bound for Glory (1976)[139]

- Coast to Coast (1980)[142]

- Cool Hand Luke (1967)[143]

- Day of Independence (2003)[144]

- Dead Man on Campus (1998)[145]

- Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry (1974)[146]

- Dreamscape (1984)[147]

- Fat City (1972),[139] based on Leonard Gardner's acclaimed 1969 novel Fat City. It is set in Stockton in the late 1950s, and was filmed by director John Huston.

- Flubber (1997)[147]

- Friendly Fire (1979)[148]

- Glory Days (1988)[149]

- God's Little Acre (1958)[150]

- High Time (1960)[147]

- Hot Shots! Part Deux (1993)[140]

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)[147]

- Inventing the Abbotts (1997)[147]

- Natzee Zombie Carnage (2019)[151]

- Oklahoma Crude (1973)[139]

- Psychopomp (2020)[152]

- Porgy and Bess (1959)[139]

- Raid on Entebbe (1977)[153]

- Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)[147]

- Rampage (1988)[154]

- R. P. M. (1970)[147]

- Steamboat Round the Bend (1935)[155]

- The Great Race[140]

- The Strawberry Statement (1970)[156]

- The Sure Thing (1985)[147]

- Valentino's Return (1989)[157]

- The World's Greatest Athlete (1973)[158]

Television

[edit]- The 1960s Western TV series The Big Valley was set just outside Stockton.

- The FX TV show Sons of Anarchy (2008–2014), is set in and near Stockton.

- Road Trip with Huell Howser Episode 142[159]

Music

[edit]- Experimental hip-hop trio Death Grips song "Stockton" refers to the city in title as well as in lyrics : "Feeders suck like stuck in Stockton", on their 2012 album No Love Deep Web.[160]

Notable people

[edit]Reagan Maui'a, a former NFL fullback, is from Stockton; he originally played for Tokay High School in nearby Lodi. Jose M. Hernandez, a famous NASA astronaut and engineer,[161] also refers to Stockton as his hometown. Chi Cheng, former bass player for the Deftones, was born and raised in Stockton. Musician Chris Isaak was born in Stockton.[162] The indie rock band Pavement was formed in Stockton in 1989 by two local musicians, Stephen Malkmus and Scott Kannberg, known originally only as "S.M." and "Spiral Stairs".[163][164] Nick and Nate Diaz, mixed martial arts fighters, are from the Stockton area. Acclaimed American author Maxine Hong Kingston was born in Stockton in 1940, graduating from Edison High in 1958. The Maxine Hong Kingston Elementary School is named after her.

Sister cities

[edit]Stockton has seven sister cities:[165]

| Country | City | Year of Partnership |

|---|---|---|

| Shizuoka | March 9, 1959;[166] October 16, 1959[167] | |

| Iloilo City | August 2, 1965 | |

| Empalme | September 4, 1973 | |

| Foshan | April 11, 1988 | |

| Parma | January 13, 1998 | |

| Battambang | October 19, 2004 | |

| Asaba | June 6, 2006 |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ a b From 15% sample

- ^ San Joaquin County employers both within and outside the city. Details of the split were not available, and San Joaquin County has been excluded from the list.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Stockton Facts". Stockton Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ a b "About Stockton". www.pacific.edu. University of the Pacific. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "AAC Winners by State and City". National Civic League. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "City Council". City of Stockton. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "City Council District 1 Councilmember Padilla". City of Stockton. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "City Council District 2 Councilmember Wright". City of Stockton. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "City Council District 3 Councilmember Blower". City of Stockton. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "City Council District 4 Councilmember Lenz". City of Stockton. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "City Council District 5 Councilmember Villapudua". City of Stockton. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "City Council District 6 Councilmember Warmsley". City of Stockton. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ "The City Manager". City of Stockton, CA. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Stockton". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ a b "QuickFacts: Stockton city, California". census.gov. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "Real Gross Domestic Product: All Industries in San Joaquin County, CA". Federal Reserve Economic Data. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Register of the Stockton (Calif.) Public Documents, 1947-". Online Archive of California. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ Christie, Jim (July 3, 2012). "How Stockton went broke: A 15-year spending binge". Reuters. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "History A Look into Stockton's Past Before the Gold Rush". City of Stockton. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ "Archaeological Investigations of the Siskiyou Trail Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument Jackson County". Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Tinkham, George Henry (1880). A History of Stockton from Its Organization up to the Present Time. W.M. Hinton & Co. p. 397.

- ^ "Captain Charles M. Weber Award". City of Stockton – Cultural Heritage Board. May 23, 2008. Archived from the original on March 22, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ Aviles, Gwen (November 15, 2019). "An ugly legacy: Latino couple finds racist covenant in housing paperwork". NBC News. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

No persons other than those wholly of the white Caucasian race shall use, occupy or reside upon any part of or within any building located on the above described real property, except servants or domestics of another race employed by or domiciled with a white Caucasian owner or tenant,

- ^ "Spirit of Stockton's Chinatown". Downtown Stockton Alliance. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ "Some State of California and City of San Francisco Anti-Chinese Legislation and Subsequent Action" (PDF). The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ "California - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- ^ Pernie, Gwenyth Laird (March 3, 2009). "Benjamin Holt (1849–1920): The Father of the Caterpillar tractor". [permanent dead link]

- ^ Lea, Ralph (February 16, 2008). "Ben Holt pioneered tractors for farming, construction, war". Lodi News-Sentinel. Archived from the original on November 11, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ^ Caterpillar Times report, May 1918, pages 5 to 8.

- ^ Eyewitness, being Personal Reminiscences of Certain Phases of the Great War, Including the Genesis of the Tank, by Major-General Sir Ernest D. Swinton. (Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1933) Throughout.

- ^ United Press, “Stockton Is Scene Of $150,000 Fire,” Riverside Daily Press, Riverside, California, Saturday January 10, 1920, Volume XXXV, Number 9, page 1.

- ^ Demoro, Harre W. (1986). California's Electric Railways. Glendale, California: Interurban Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-916374-74-7.

- ^ "History of Stockton Gurwara". Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ "Historic California Posts: Stockton Ordnance Depot". californiamilitaryhistory.org. The California State Military Museum. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "The Cornell Daily Sun 27 April 1937 — The Cornell Daily Sun". cdsun.library.cornell.edu. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ "Stockton (detention facility)". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ Echo-Hawk, Walter (2010). In the Courts of the Conqueror : the 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided. New York: Fulcrum. ISBN 978-1-55591-788-3. OCLC 646788565.

- ^ The future of the past : archaeologists, Native Americans, and repatriation. Tamara L. Bray. New York: Garland Pub. 2001. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-136-54352-4. OCLC 817236389.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Ready, no longer Rough". Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ McGrath, M. (2016). "Stockton, California: A My Brother's Keeper Community". National Civic Review. 105 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1002/ncr.21261.

- ^ Christie, Les (August 14, 2007). "California cities fill top 10 foreclosure list". Money.cnn.com. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Christie, Les (December 2, 2008). "Home sellers suffer amid wave of foreclosures". Money.cnn.com. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ a b "America's Most Dangerous Cities". Forbes. April 23, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ "Forbes Magazine Names Worst Places to Live in America". Fox News. March 24, 2010. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Smith, Scott (October 4, 2013). "Council approves Chap. 9 exit plan". The Record. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ a b Marcum, Diana (November 6, 2013). "Stockton voters approve of new tax measure for bankrupt city". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ "Stockton, California Chapter 9 Voluntary Petition" (PDF). PacerMonitor. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ^ Lifsher, Marc; Petersen, Melody (October 30, 2014). "Judge approves Stockton bankruptcy plan; worker pensions safe". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ "SEED". Stocktondemonstration.org. March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ "Who We Are". economicsecurityproject.org. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "Can $500 a month change a city? Stockton tests universal basic income". SFChronicle.com. January 2, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ "California city fights poverty with guaranteed income". Reuters. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ "Guaranteed Income Increases Employment, Improves Financial and Physical Health". stocktondemonstration.org. March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "Average Weather in Stockton, California, United States, Year Round - Weather Spark". weatherspark.com. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". W2.weather.gov. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "San Joaquin River Basin Integrated Interim Feasibility Report / Environmental Impact Statement" (PDF). US Army Corps of Engineers. January 2018.

- ^ James, Ian (January 18, 2023). "California faces catastrophic flood dangers — and a need to invest billions in protection". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for STOCKTON, CA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ a b "Stockton (city), California". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c "California – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Stockton city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Stockton city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Stockton city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Stockton city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. News Special Report: Stockton, Calif., Is the Most Diverse City in America". U.S. News & World Report. January 22, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ David Siders (March 5, 2010). "Stockton area tops poll of nation's most obese regions". Recordnet.com. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ Money.MSN.com 8/2012

- ^ a b Rogers, Abby (November 1, 2012). "The 25 Most Dangerous Cities in America - Yahoo! Finance". Finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "America's most and least literate cities" Archived February 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. 247wallst.com, February 11, 2013.

- ^ turnto23.com

- ^ City of Stockton, Annual Comprehensive Financial Report, for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 2022

- ^ "Stockton Symphony Association – Stockton, California". Stockton Symphony Association. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ "The Brubeck Institute". University of the Pacific. Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ "Delta instructor hopes to prove live jazz can draw Stockton fans". The Record. San Joaquin Media Group, a division of Dow Jones Local Media Group. October 19, 2006. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ Ian Hill (June 28, 2007). "Apollo Night marks decade of entertainment". The Record. San Joaquin Media Group, a division of Dow Jones Local Media Group. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ "Stockton Live". SMG Stockton. 2019.

- ^ "Entertainment". Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ Stockton Opera. "Stockton Opera".

- ^ Rachael Myrow (September 2, 2013). "Stockton's Little Manila: the Heart of Filipino California". KQED. San Francisco. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

"Little Manila: Filipinos in California's Heartland". KVIE. 2014. Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

"New on SF State bookshelf". SF State News. San Francisco State University. April 11, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

Deborah Kong (December 26, 2002). "Filipino Americans work to preserve heritage". Star Bulletin. Honolulu. Associated Press. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

Steven Winn (October 8, 2008). "'Romance of Magno Rubio': Filipino homecoming". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

The Secrets of Giron Arnis Escrima. Tuttle Publishing. March 15, 1998. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8048-3139-0.

Angeles Monrayo Raymundo (2003). Tomorrow's Memories: A Diary, 1924-1928. University of Hawaii Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-8248-2688-8.

Austin, Leonard (1959). Around the World in San Francisco. San Francisco: Fearon Publishers. pp. 26–28. LCCN 59065441. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

Jon Sterngass (January 1, 2009). Filipino Americans. Infobase Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4381-0711-0. - ^ Conclara, Rommel (March 5, 2015). "Fil-Am museum to open in California". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ "Filipino American National Historic Society Museum".

- ^ downtownstockton.org

- ^ San Joaquin International Film Festival. "San Joaquin International Film Festival".

- ^ "Stockton San Joaquin Asparagus Festival: April 20-22, 2018". SeeCalifornia.

- ^ "The Brubeck Festival". Brubeck Institute. University of the Pacific. Archived from the original on August 31, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ "2016 Nagar Kirtan Route". Gurdwara Sahib Stockton. April 2, 2016. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ Michael Fitzgerald (August 7, 2016). "Obon Odori and Cultural Bazaar a hit with the crowd". Recordnet.com. The Record.

- ^ Nicholas Filipas (August 11, 2018). "Filipinos celebrate Barrio Fiesta with heavy hearts". Recordnet.com. The Record.

- ^ "Stockton Beer Week". Downtown Stockton Alliance. 2018.[dead link]

- ^ Almendra Carpizo (October 27, 2018). "Downtown Stockton Comes Alive for Day of the Dead". Recordnet.com. The Record.

- ^ baseball-reference.com [full citation needed]

- ^ milb.com [full citation needed]

- ^ milb.com Stockton Ports history[full citation needed]

- ^ web.pacific.edu Archived February 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Where the Mighty Casey Struck Out". Thediamondangle.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ Sherdog.com. "Nick Diaz MMA Stats, Pictures, News, Videos, Biography - Sherdog.com". Sherdog. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Sherdog.com. "Nate Diaz MMA Stats, Pictures, News, Videos, Biography - Sherdog.com". Sherdog. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Edwards, James (March 6, 2016). "Who is Nate Diaz? 5 things you need to know the man who beat Conor McGregor". Daily Mirror. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ "Nate Diaz Will Teach Your Kids | FIGHTLAND". Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ "Nate Diaz Academy | Gracie Fighter Lodi | Gracie Jiu-Jitsu | Stockton, CA". natediaz209.com. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ "Pixie Woods - City of Stockton, CA". stocktongov.com.

- ^ "Mayor Kevin J. Lincoln, II". stocktongov.com. January 4, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ^ "City Council - City of Stockton, CA".

- ^ "City of Stockton, CA". Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ "San Joaquin County". San Joaquin County. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ "Slaughter in A School Yard". Time. June 24, 2001. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ DuHain, Tom (September 3, 2013). "Stockton PD reaches highest staff in 5 years". KCRA. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ Klocke, Mike (November 3, 2013). "Important step to filling out the thin blue line". The Record (Stockton). Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ BELL, DEVON. "A POLICE FOUNDATION CRITICAL INCIDENT REVIEW OF THE STOCKTON POLICE RESPONSE TO THE BANK OF THE WEST ROBBERY AND HOSTAGE-TAKING" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 18, 2015.

- ^ Phillips, Roger. "Third hostage in Bank of the West robbery speaks".

- ^ a b "By the numbers: Here are the 20 'most dangerous' cities in America". Tribune Media Company. May 8, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Anderson, Jason (October 12, 2013). "Violent crime continues downward trend". The Record (Stockton). Archived from the original on December 10, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ Goldeen, Joe (December 28, 2012). "Patience urged as new Ceasefire kicks in". The Record. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Harless, William (October 14, 2013). "Cities Use Sticks, Carrots to Rein In Gangs". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ "California Response Times Investigated | Firehouse". Firehouse. KCRA. November 17, 2005. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ "City of Stockton, CA Homepage- Official City Government Website". user.govoutreach.com. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ "Central Valley Business Times". www.centralvalleybusinesstimes.com. May 19, 2010. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ Funkhouser, Mark (April 8, 2013). "Sharing the Burdens of a Broken City". www.governing.com.

- ^ C. Johnson, Steven; Francescani, Chris. "Public Safety Compensation". www.firefighterclosecalls.com. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ "2015 Stockton Fire Department Year In Review". 2015 Stockton Fire Department Year In Review. February 27, 2016. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ "A Broad Selection of Courses". Archived from the original on January 17, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ "Hollywood at Pacific". University of the Pacific. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ "San Joaquin Delta College Fact Sheet" (PDF). deltacollege.edu/. San Joaquin Delta College. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ "San Joaquin RTD". Sanjoaquinrtd.com. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ Wanek-Libman, Mischa (September 15, 2020). "The Stockton Diamond project lands $20-million BUILD grant". Mass Transit. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "Stockton Metropolitan Airport (SCK)". Sjgov.org. July 1, 2012. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Caltrans Port of Stockton Fact Sheet" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ "The Port of Stockton Today". Portofstockton.com. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "Port of Stockton 2014 Annual Report" (PDF). Portofstockton.com. pp. 22–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "General Services". Portofstockton.com. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "Port of Stockton, California". Portofstockton.com. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Michael (September 13, 2013). "AM radio heartbeat faint but still kicking". recordnet.com. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Ian Hill (July 10, 2005). "Fantastic return". Recordnet.com. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grant, Lee (July 2, 1977). "Waiting to Be Discovered". Los Angeles Times. p. 10. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c Burrell, Jackie (June 24, 2016). "Travel Top 10: Films shot in Stockton". The Mercury News. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "Rob Schneider collapses on film set". Visalia Times-Delta (Visalia, California). June 30, 2006. p. 19. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Masullo, Robert A. (April 23, 1980). "Candid Actor Unpromotes A Film". The Sacramento Bee. p. 81. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "For Movie Scene Roberts Island As a Backdrop". Tracy Press (Tracy, California. November 14, 1966. p. 4. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Lachtman, Howard. "'Day of Independence' tells timeless tale". The Stockton Record. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, G. Allen (August 24, 1998). "'Dead Man On Campus' black comedy at its worst". Santa Maria Times. p. 9. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Hobbs, Carolyn (October 17, 1973). "For 'Dirty Mary Crazy Larry' cast". Tracy Press (Tracy, California). p. 13. Retrieved February 27, 2022.