Expedition to Earth

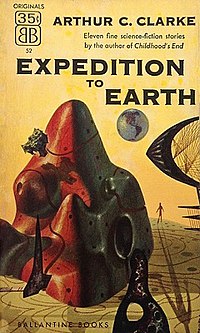

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Arthur C. Clarke |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Richard Powers[1] |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Ballantine Books |

Publication date | 1953 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (paperback) |

| Pages | 167 |

Expedition to Earth (ISBN 0-7221-2423-6) is a collection of science fiction short stories by English writer Arthur C. Clarke.

There are at least two variants of this book's table of contents, in different editions of the book. Both variants include the stories "History Lesson" (1949) and "Encounter in the Dawn" (1953), but only one story is included under its own title; the other story is included under the title "Expedition to Earth". Variants differ in the story that is included under its own title.

Contents

[edit]This collection, originally published in 1953, includes:

- "Second Dawn"

- "If I Forget Thee, Oh Earth"

- "Breaking Strain"

- "History Lesson" (as "Expedition to Earth" in the British Edition, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1954)

- "Superiority"

- "Exile of the Eons" (as "Nemesis" in the British Edition, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1954)

- "Hide-and-Seek"

- "Expedition to Earth" (as "Encounter in the Dawn" in the British Edition, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1954)

- "Loophole"

- "Inheritance"

- "The Sentinel"

Reception

[edit]Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas selected the collection as one of the best sf books of 1953, praising the stories' "humor, technical ideas, science-fictional thinking and all-around excellence."[2] Groff Conklin said that "The stories are continuously fascinating" and "exhibiting their author's versatility".[3] P. Schuyler Miller praised it as "an excellent collection . . . span[ning] the whole range of [Clarke's] talents".[4] Writing in the Hartford Courant, reviewer R. W. Wallace declared that the stories "show [Clarke] as a more skilled literary artist" than even his novel Childhood's End had.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ "Publication: Expedition to Earth".

- ^ "Recommended Reading," F&SF, March 1954, p.93.

- ^ Conklin, Groff (May 1954). "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 129–133.

- ^ "The Reference Library", Astounding Science Fiction, November 1954, p.150

- ^ "Time and Space", Hartford Courant, February 7, 1954, p.SM19

Sources

[edit]- Tuck, Donald H. (1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent. p. 101. ISBN 0-911682-20-1.

External links

[edit]- Expedition to Earth title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database