Queen's House

| Queen's House | |

|---|---|

The Queen's House, viewed from the main gate | |

| General information | |

| Location | Greenwich London, SE10 United Kingdom |

| Construction started | 1616 |

| Completed | 1635 |

| Client | Anne of Denmark |

| Owner | Royal Museums Greenwich |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Inigo Jones |

| Designations | Grade I listed Scheduled monument |

| Website | |

| Queen's House | |

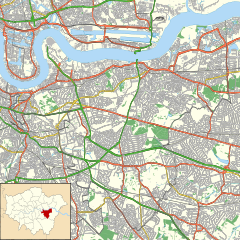

Queen's House is a former royal residence in the London borough of Greenwich, which presently serves as a public art gallery. It was built between 1616 and 1635 on the grounds of the now demolished Greenwich Palace, a few miles downriver from the City of London. In its current setting, it forms a central focus of the Old Royal Naval College with a grand vista leading to the River Thames, a World Heritage Site called, Maritime Greenwich. The Queen's House architect, Inigo Jones, was commissioned by Queen Anne of Denmark in 1616 and again to finish the house in 1635 by Queen Henrietta Maria. The House was commissioned by both Anne and Henrietta as a retreat and place to display and enjoy the artworks they had accumulated and commissioned; this includes a ceiling of the Great Hall that features a work by Orazio Gentileschi titled Allegory of Peace and the Arts.

Queen's House is one of the most important buildings in British architectural history, due to it being the first consciously classical building to have been constructed in the country. It was Jones's first major commission after returning from his 1613–1615 grand tour[1] of Roman, Renaissance, and Palladian architecture in Italy. Some earlier English buildings, such as Longleat and Burghley House, had made borrowings from the classical style, but the structure of these buildings was not informed by an understanding of classical precedents. Queen's House would have appeared revolutionary during this period. Although it diverges from the mathematical constraints of Palladio, Jones is often credited with the introduction of Palladianism with the construction of the Queen's House. Jones' unique architecture of the Queen's House also includes features like the Tulip Stairs, an intricate wrought iron staircase that holds itself up, and the Great Hall, a perfect cube.

After its brief use as a home for Royalty, the Queen's House was incorporated into use for the complex for the expanding Royal Hospital for Seamen. Neoclassical colonnades wings and buildings were added in the early nineteenth century for a Seaman's school. Today the building is both a Grade I listed building and a scheduled monument; A status that includes the 115-foot-wide (35 m) axial vista to the River Thames. The house is now serves as part of the National Maritime Museum and is used to display parts of its substantial collection of maritime paintings and portraits.

Early history

[edit]Queen's House is located in Greenwich, London. It was built as an adjunct to the Tudor Palace of Greenwich, previously known before its redevelopment by Henry VII,[2] as the Palace of Placentia; Which was a rambling, red-brick, building in a vernacular style. This would have presented a dramatic contrast of appearance to the newer, white-painted House. The original building was intended as a pavilion with a bridge over the London-Dover road, running between high walls through the park of the palace.[3] Construction of the house began in 1616, but work on the house stopped in April 1618 when Anne became ill and died the following year. Work restarted when the house was given to the queen consort, Henrietta Maria, in 1629 by King Charles I. The house was structurally complete by 1635.[4][5]

However, the house's original use was short, no more than seven years; The English Civil War began in 1642 and swept away the court culture from which it sprang. Although some of the house's interiors survive, including three ceilings and some wall decorations, none of the interior remains in its original state. The process of dismantling the house began as early as 1662, when masons removed a niche and term figures and a chimneypiece.[6]

Artworks that had been commissioned by Charles I for the house, now reside elsewhere; These include a ceiling panel by Orazio Gentileschi, Allegory of Peace and the Arts, which is now installed at Marlborough House, London,[7] a large Finding of Moses, now on loan from a private collection to the National Gallery, London,[8] and a matching Joseph and Potiphar's Wife, still in the Royal Collection.[9]

The Queen's House, though it was scarcely being used, provided the distant focal centre for Sir Christopher Wren's Greenwich Hospital, with a logic and grandeur that has seemed inevitable to architectural historians but in fact depended on Mary II's insistence that the vista to the water from the Queen's House not be impaired.[10]

Architecture

[edit]Built by Inigo Jones in the seventeenth century, the Queen's House is England's first classical building. Inigo Jones was commissioned by Anne of Denmark in 1616 to build the unique house. At her death in 1619, the house was unfinished. Jones completed the house for Queen Henrietta Maria in 1635.[11] The Queen's House is unique in style and characteristics compared to other English buildings of the time. Jones created a first-floor central bridge that joined the two halves of the building. Inigo Jones was heavily influenced by Italian Renaissance architecture and the Palladian style, created by Andrea Palladio. Jones applied the characteristics of harmony, detail, and proportion to the commission. Rather than being in the traditional, red-brick Tudor style like the then existing palace, the house is white and is known for its elegant proportions. Jones felt compelled to reflect political circumstances of the time through his use of his Orders, reflected in his "Roman Sketchbook" notes. In early designs of the Queen's house, Jones experimented with using the Corinthian Order in public, which at the time was used as court architecture and was viewed as "masculine and unaffected".[12]

Two preliminary drawings have been associated with Anne of Denmark's commission. The first plan includes a rectangular villa with a circular staircase adjacent to a vaulted square hall with six pilasters along the exterior. The second plan is composed of an H-shaped building with a columnar bay and a balcony, which fits two of the elevations of the Queen's House.[12] The completed Queen's House, finished under the request of Queen Henrietta Maria, reflects a public restraint mentioned in Jones' "Roman Sketchbook". Between 1632 and 1635 a central loggia was added to the south front and Columns were limited to this area. The columns were switched from Corinthian to Ionic to reflect the strictures of Serlio, being made for matrons.[12]

Inigo Jones' design is famous for two of its aspects: the Great Hall and the Tulip Staircase. The Great Hall is the centerpiece of the Queen's House and holds a first-floor gallery that overlooks geometric-styled black and white marble flooring. The Great Hall is recognizable and innovative for its architecture; The shape of this hall is perfect cube, measuring 40 ft in each direction.[13] Much like Jones' inspiration for the rest of the Queen's House, Jones used the rules of proportion created by Palladio.[13]

The Tulip Staircase was an unusual feature during this period and the first of its kind. Made of ornate wrought iron, it is Britain's first geometric and unsupported staircase. Each tread is cantilevered from the wall and supported by the step below, a design invented by the mason, Nicholas Stone. Each step is interlocked along the bottom of the riser.[18] Jones found inspiration for the staircase, and the glass lantern above, from Palladio's Carita Monastery, where he noted that the staircases with a void in the center "succeed very well because they can have light from above".[13] Jones hired Nicholas Stone to lay the black and white flooring which mirrored the design of the ceiling.

Patron

[edit]Anne of Denmark

[edit]Anne of Denmark, the wife of James I of England, was an important patron of the arts. Anne commissioned her frequent collaborator, Inigo Jones, to refurbish the Queen's House in Greenwich.[14] Although the Queen's House was not completed before her death in 1619, Anne was able to use the palace at Greenwich as a personal gallery before her death. Both James I and Anne had private galleries and fashioned them in similar ways. Jemma Field describes the spaces as a place of political significance; "All objects and furnishings were appraised as signs of Stuart wealth, merit, and honour".[15][16] Anne of Denmark's project may have been influenced by her knowledge of garden buildings and hunting lodges in Denmark, and her brother Christian IV of Denmark sent two Danish stonemasons to work for her at Greenwich for nine months.[17]

Queen Henrietta Maria

[edit]Henrietta Maria, the wife of Charles I, son of Anne and James, inherited the rights to Greenwich Park in 1629. She commissioned Inigo Jones to return and finish the Queen's House between approximately 1629 and 1638.[14] As an important patron for contemporary artists, Henrietta acquired and commissioned many works of art for the Queen's House. Henrietta used the palace as a "House of Delights" and filled the home with spectacular pieces of art, including the Great Ceiling.[18]

Allegory of Peace and the Arts (Ceiling by Orazio Gentileschi)

[edit]

Orazio Gentileschi, a favorite at the court of Charles I, was commissioned by Queen Henrietta Maria to decorate her "House of Delights". By Gentileschi's death in 1639, the Queen's House contained about half of Gentileschi's English works, including the ceiling of the Great Hall from 1635 to 1638.[19] The central work of this hall features the Allegory of Peace and the Arts, a central tondo surrounded by eight other canvases. The ceiling creates a visual celebration of the reign of King Charles I and his encouragement of peace and the liberal arts.[20] Gentileschi Illuminates the taste and patronage of Henrietta Marie by embodying the power of women throughout the ceiling, all but one of the twenty-six figures are women.[20]

The composition of the ceiling includes a large central tondo with four rectangular canvases on each side of the ceiling and four smaller tondos on the corners. The central tondo, the personification of Peace is depicted floating on a cloud and is surrounded by the figures representing the Liberal Arts, Victory, and Fortune. The surrounding panels depict the nine Muses, and the personifications of Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, and Music.[20] The image of Peace, in the central tondo, is seated on a cloud and holding an olive branch in one hand and a staff in the other, embodying the message that Peace is a product of good government and rule because of the encouragement of knowledge, learning, creativity while remaining within the realm of Reason.[20] Peace, the only male figure, is positioned in the center of the panel portraying him as the most important and the central quality by allowing the others to be around him. The other twelve females are the personifications of the trivium(Grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and quadrivium(arithmetic, astronomy, music, and geometry) that make up the Liberal Arts.[20]

In 1708, Gentileschi's series of nine paintings were removed, given by Queen Anne to Sarah Churchhill.[21] They were installed in Marlborough House, St James, where they can still be viewed today.[21]

For the first time since 1639, when Gentileschi worked on the ceiling, another artist has recently worked on the ceiling, Turner Prize winner, Richard Wright.[21] In 2016, Wright and his team of five assistants worked together to fill the empty spaces of the ceiling left behind by the Gentileschi panels.[22] The team used a series of scaffolded flat beds to support them while they transferred a sketch to the ceiling, applied size to the outline, and then covered it with gold leaf.[22] Wright took influence from the geometric patterning on the floor, the intricate details of the tulip staircase, and created a ceiling that reflects the Queen's House's geometry, beauty, and intracity.

Construction of the Greenwich Hospital

[edit]

Although the house survived as an official building, being used for the lying-in-state of Commonwealth Generals-at-Sea Richard Dean (1653) and Robert Blake (1657), the main palace was progressively demolished between 1660 and 1690. Between 1696 and 1751, to the master-plan of Sir Christopher Wren, the palace was replaced by the Royal Hospital for Seamen (now referred to as the Old Royal Naval College).[23] Due to the positioning of Queen's House, and Queen Mary II's request that it retain its view of the river, Wren's Hospital architectural design was composed of two matching pairs of courts that were separated by a grand 'visto' the exact width of the house(115 ft).

Wren's first plan, which was blocking the view to the Thames, became known to history as "Christopher Wren's faux pas". The whole ensemble at Greenwich forms an architectural vista that stretches from the Thames to Greenwich Park, and is one of the principal features that in 1997 led UNESCO to inscribe 'Maritime Greenwich' as a World Heritage Site.

19th-century additions

[edit]From 1806 the house was used as the center of the Royal Hospital School for the sons of seamen. This change in use necessitated new accommodations; Wings and a flanking pair were added to east and west and connected to the house by colonnades (designed by London Docks architect Daniel Asher Alexander). In 1933, the school moved to Holbrook, Suffolk and its Greenwich buildings, including the house, were converted and restored; They became the new National Maritime Museum (NMM), created by Act of Parliament in 1934 and opened in 1937.

Following construction of the cut-and-cover tunnel between Greenwich and Maze Hill stations, the grounds immediately to the north of the house were reinstated in the late 1870s. The tunnel comprised the continuation of the London and Greenwich Railway and opened in 1878.

Recent years

[edit]

In 2012, the grounds to the south of the Queen's House were used to house a stadium for the equestrian events of the Olympic Games.[24] The grounds were used to stage the modern pentathlon, while the Queen's House in particular was used as a VIP center for the games.

Work to prepare the Queen's House involved some internal re-modelling and work on the lead roof to prepare it for security and camera installations.[citation needed] The house underwent a 14-month restoration beginning in 2015, and reopened on 11 October 2016.[25] The house had previously been restored between 1986 and 1999, with contemporary insertions that modernised the building. The modernization created controversial due to the new ceiling in the main hall created by artist Richard Wright, a Turner prize winner. In some quarters, it provoked some debate: an editorial in The Burlington Magazine, November 1995, alluded to "the recent transformation of the Queen's House into a theme-park interior of fake furniture and fireplaces, tatty modern plaster casts and clip-on chandeliers".[26]

Current use

[edit]The house is now primarily used to display the museum's substantial collection of marine paintings and portraits of the seventeenth to twentieth centuries, and for other public and private events. It is normally open to the public daily, free of charge, as well as other museum galleries and the seventeenth-century Royal Observatory, Greenwich, which is also part of the National Maritime Museum.

In Autumn 2022, a 1768 painting by the artist Tilly Kettle went on permanent display.[27] The painting depicts Sir Samuel Cornish, 1st Baronet, Richard Kempenfelt and Thomas Parry on HMS Norfolk and was purchased by the National Maritime Museum, with assistance from the Society for Nautical Research.[27]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The phrase 'Grand Tour' was unknown until approximately 1670, but in essence, Jones's tour of Germany, Italy and France, incorporated many of the elements of the later tour.

- ^ The Palace of Placentia was redeveloped circa 1500

- ^ Cook, Olive (1974). The English Country House. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 112–116. ISBN 0-500-24090-6.

- ^ "History of the Queen's House". Royal Museums Greenwich.

- ^ Detailed accounts of the building project are given in London County Council, Survey of London, Howard Colvin, ed. The History of The King's Works, Volume IV, 1485–1660, (Part II 9) and in John Bold, Greenwich: An Architectural History of the Royal Hospital for Seamen and the Queen's House (Yale University Press) 2000.

- ^ John Newman, noting this, identified a chimneypiece likely to have come from the Queen's House, at Charlton House, barely three miles away; for its design it drew upon an engraving in Jean Barbet's Livre d'architecture (1633); Newman, "Strayed from the Queen's House?" Architectural History 27, Design and Practice in British Architecture: Studies in Architectural History Presented to Howard Colvin (1984:33–35).

- ^ R. W. Bissell, Orazio Gentileschi and the Poetic Tradition in Caravaggiesque Painting[1981], cat. no. 70, pp 195–98.

- ^ National Gallery Archived 7 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lloyd, Christopher, The Queen's Pictures, Royal Collectors through the centuries, p. 102, National Gallery Publications, 1991, ISBN 0-947645-89-6. This is usually at Hampton Court Palace.

- ^ John Bold, Greenwich: An Architectural History of the Royal Hospital for Seamen and the Queen's House (Yale University Press) 2000.

- ^ "Inigo Jones and the Queen's House". www.rmg.co.uk (Royal Museums Greenwich). Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Vaughn, Hart (2010). "Inigo Jones, 'Vitruvius Britannicus'". Architectural History. 53: 1–39. doi:10.1017/S0066622X00003853. JSTOR 41417501. S2CID 187410282.

- ^ a b c Chettle, George H. "Architectural Description". Survey of London Monograph 14, the Queen's House, Greenwich: 59–83 – via British History Online.

- ^ a b "Royal Portraits". www.rmg.co.uk (Royal Museums Greenwich). Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: The material and visual culture of the Stuart courts, 1589-1619 (Manchester, 2020), p. 93.

- ^ Payne, M. T. W. (2001). "An Inventory of Queen Anne of Denmark's 'Ornaments, Furniture, Householde Stuffe, and Other Parcells' at Denmark House, 1619". Journal of the History of Collections. 13: 23–44. doi:10.1093/jhc/13.1.23.

- ^ Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: The material and visual culture of the Stuart courts, 1589-1619 (Manchester, 2020), p. 67.

- ^ "Private delights, public display- a hidden history of the Queen's House". www.rmg.co.uk (Royal Museums Greenwich). Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Christiansen, Keith; Mann, Judith W. (2001). Orazio and Artemesia Gentileschi. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. pp. 7–35. ISBN 1588390063.

- ^ a b c d e McCormack, Catherine (2019). The Art of Looking Up. London: White Lion Publishing. pp. 3–43. ISBN 978-1588390066.

- ^ a b c "Great Hall Ceiling". Royal Museum Greenwich. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Richard Wright to create spectacular artwork in the Queen's House". Royal Museums Greenwich. 2016.

- ^ The Royal Hospital for Seamen is usually known as Greenwich Hospital.

- ^ London 2012 Archived 4 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine See "Greenwich Park Brochure"

- ^ "The king of England gave his wife this house to forgive her for shooting his best hunting dog". Quartz. 8 October 2016.

- ^ "Greenwich grotesquerie", The Burlington Magazine 137 No. 1112 (November 1995:719); the occasion was the Ministry of Defence and the Department of National Heritage's issuance of a glossy brochure through estate agents soliciting long-term leases for Wren's Old Royal Naval Hospital, Greenwich.

- ^ a b Gazard, Catherine (2022). "Tilly Kettle's Portrait of Vice-Admiral Sir Samuel Cornish, Captain Richard Kempenfelt and Thomas Parry". The Mariner's Mirror. 108 (4). Society for Nautical Research: 462–468. doi:10.1080/00253359.2022.2117460. S2CID 253161540.

External links

[edit]- Houses completed in 1635

- Houses in the Royal Borough of Greenwich

- Country houses in London

- Royal buildings in London

- Royal residences in the Royal Borough of Greenwich

- Grade I listed houses in London

- Grade I listed museum buildings

- Scheduled monuments in London

- Inigo Jones buildings

- Jacobean architecture in the United Kingdom

- Palladian architecture in England

- Museums in the Royal Borough of Greenwich

- 1635 establishments in England

- Anne of Denmark

- Henrietta Maria of France