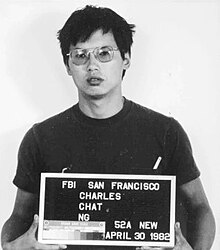

Charles Ng

Charles Ng | |

|---|---|

Ng in a 2018 prison photograph | |

| Born | Ng Chi-tat 24 December 1960 |

| Nationality | British Dependent Territories citizen (1983–1997) British National (Overseas) (1997–present) |

| Conviction(s) |

|

| Criminal penalty | Death by lethal injection (de jure) |

| Details | |

| Victims | 11 convictions, 25 total suspected[1] |

Span of crimes | 1983–1985 |

| State(s) | Calaveras County, California |

Date apprehended | July 6, 1985[2] |

| Imprisoned at | California Medical Facility |

| Charles Ng | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 吳志達 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 吴志达 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Charles Chi-tat Ng (born Ng Chi-tat) (Chinese: 吳志達; Jyutping: ng4 zi3 daat6; born 24 December 1960) is a convicted Hong Kong-born serial killer who committed numerous crimes in the United States. He is believed to have raped, tortured, and murdered between eleven and twenty-five victims with his accomplice Leonard Lake at Lake's cabin in Calaveras County, California, 60 miles (96 km) from Sacramento, between 1983 and 1985.[3] After his arrest and imprisonment in Canada on robbery and weapons charges, followed by a lengthy dispute between Canada and the U.S.,[4] Ng was extradited to California, tried, and convicted of eleven murders.[1] He is currently on death row at California Medical Facility.

Early life

[edit]Charles Ng was born as Ng Chi-tat in British Hong Kong,[5] the youngest of three children and only son of a wealthy Hongkonger executive and his wife. As a child, Ng was harshly disciplined and abused by his father.[6]

As a teenager, he was described as a troubled loner and was expelled from several schools. After his arrest for shoplifting at age 15, he went, at his father's insistence, to Bentham Grammar School, a boarding school in North Yorkshire, England.[4] Not long after arriving, Ng was expelled for stealing from other students and returned to Hong Kong.[citation needed]

Ng moved to the United States on a student visa in 1978 and studied biology at the College of Notre Dame in Belmont, California.[7] He dropped out after one semester.[8]: 91 Soon after, he was involved in a hit and run accident, and to avoid prosecution he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps.

U.S. Marine Corps

[edit]Ng joined the Marines in October 1979 with the help, he claimed, of a recruiting sergeant and false documents attesting to his birthplace as Bloomington, Indiana.[8]: 91 After less than a year of service, he was arrested by military police for stealing automatic weapons from the Kaneohe Bay base armory. Facing court-martial, Ng escaped custody in 1980 and made his way back to northern California, where he met Leonard Lake.[7]

In 1982, federal authorities raided the mobile home Ng and Lake shared in Ukiah, seizing a large stash of illegal weapons and explosives. Lake was released on bond, but he jumped bail and hid at a remote cabin owned by his wife, Claralyn Balazs, in Wilseyville, a community in Calaveras County located in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Ng was captured and returned to Marine custody and pleaded guilty to the charges of theft and desertion. Under the terms of this plea deal, he was paroled and dishonorably discharged in 1984 after serving eighteen months in the military stockade at the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.[citation needed]

Murders

[edit]After his release from Leavenworth, Ng rejoined Lake, who was still living at the Wilseyville cabin. By then, Lake and Balazs had divorced but remained on good terms. Next to the cabin, Lake had built a structure described in his journals as a "dungeon." Before Ng's arrival, Lake is believed to have already murdered his brother Donald, whom he lured to the cabin and shot in his sleep in 1983, and his friend and best man Charles Gunnar. Gunnar's body was unearthed from the Wilseyville property in 1992.[8]: 92 [9]

Over the next year, Lake and Ng began a pattern of kidnapping and murder of men, women, and children. According to court records, they killed the men and infants immediately, whereas they subjected women to a period of enslavement, rape, and torture before killing them.[8]: 92 [9]

In July 1984, an Asian American man broke into and robbed the apartment of Don Giulietti, a San Francisco disc jockey, and his roommate, Richard Carrazza, shooting both men in the process. Giulietti died in the attack, but Carrazza, the only known survivor victim of either Lake or Ng, later identified Ng as his assailant. Soon afterward, Ng managed to get a job at a Bay Area moving company. The duo's rampage would have gone on longer were it not for Ng's kleptomania. On June 2, 1985, Lake and Ng entered the South City Lumber Store in South San Francisco. An employee observed Ng stealing a $75 vise and called the police. When confronted by the employee, Ng tossed the vise into the trunk of a 1980 Honda Prelude in the parking lot, then fled on foot. The police arrived minutes later. An officer looked into the car's trunk and saw the stolen vise along with a .22 caliber pistol equipped with an illegal silencer. Lake asserted there was a misunderstanding and that he had paid for the vise; he was arrested for possessing the illegally modified weapon.[citation needed]

The arresting officer noticed that Lake bore no resemblance to the photo on his California driver's license, which bore the name of Robin Scott Stapley, a San Diego man reported missing by his family several weeks earlier. The Honda was registered to Paul Cosner, who disappeared from San Francisco on November 2, 1984, after leaving his apartment to show the car to someone interested in purchasing it. The car's license plate was registered to yet another missing person, Lonnie Bond, of Wilseyville. The gun was registered to Stapley. While in custody, Lake admitted his real identity and that of his accomplice, Ng. He then asked for a pencil, a piece of paper, and a glass of water. Left alone in an interrogation room, Lake wrote a note to his ex-wife, then swallowed a cyanide capsule he had hidden in his jacket. Lake was rushed to nearby Kaiser Hospital. He was pronounced dead on June 6.[8]: 93

Upon further examination of the Honda Prelude, investigators found a bullet hole in the car's roof, along with blood spatter, a stun gun, and several unspent bullets. Under the passenger seat, a utility bill was found in the name of Lake's ex-wife, Claralyn Balazs, with a Wilseyville address. On June 4, San Francisco Police detectives and Calaveras County Sheriffs investigators searched the Wilseyville cabin with Balazs's permission. In one of the bedrooms, they discovered video equipment belonging to Harvey Dubs, who had vanished from his San Francisco apartment along with his wife Deborah, and their infant son, Sean, in July 1984.[citation needed]

Investigators also found vehicles belonging to Bond and Stapley parked on the property. Bond had rented a house just 50 yards from Lake's cabin with his girlfriend Brenda O'Connor and their infant son. Stapley, a friend of Bond's, had also been staying at the house. Detectives found the house empty and the rent unpaid for several months. Next to the driveway stood a cinder-block bunker that Lake had constructed. Inside the bunker, investigators found a copy of The Collector as well as tools, handcuffs, women's clothing, and makeup. In his teenage years, Lake had read a 1963 John Fowles novel called The Collector, which tells the story of a man who captures a woman (named Miranda) and keeps her as a slave in the hopes she would eventually fall in love with him. Lake was fascinated by this novel, and used the book as inspiration for what he called "Operation Miranda". Posted on a wall was a list of typewritten rules for female captives to follow, along with pictures of 21 women, some of them nude. Behind one wall, through a hidden door, was a tiny windowless cell with a small mattress and a bucket that may have been used as a toilet. Investigators believed that women had been held in the cell as Lake's prisoners.[citation needed]

In a makeshift burial site nearby, police unearthed roughly 45 pounds of burned and crushed human bone fragments, corresponding to a minimum of 11 bodies.[8]: 94

In addition to Bond, O'Connor, the Dubs, and their children, other victims included Paul Cosner, Randy Jacobsen, Mike Carroll, Kathy Allen, Jeff Gerald, Robin Stapley, Clifford Peranteau, relatives and friends who came looking for Bond and O'Connor, and two gay men.[9]

They also found a hand-drawn "treasure map", leading them to two buried five-gallon buckets. One contained envelopes with names and victims' identifications, suggesting that the total number of victims might have been as high as 25. In the other bucket were Lake's handwritten journals for the years 1983 and 1984, and two videotapes documenting the torture of two of their victims. On one of the tapes, labeled "M-Ladies", Charles Ng is seen telling victim Brenda O'Connor, as he cuts her shirt off with a knife, "You can cry and stuff, like the rest of them, but it won't do any good. We are pretty … cold-hearted, so to speak." In another part of the tape, Kathy Allen is seen seated in a chair, with Leonard Lake warning her, "If you don't go along with us, we'll probably take you into the bed, tie you down, rape you, shoot you, and bury you." In the other, Deborah Dubs is shown being assaulted so severely that she "could not have survived".[8]: 94

After fleeing the lumber yard, Ng arrived at Balazs's residence and told her that he had to leave town immediately. Balazs drove him to San Francisco International Airport where he boarded a flight to Chicago, using the alias "Mike Kimoto". A friend of Ng drove him from Chicago to Detroit, and across the border into Canada. He eventually settled in Calgary, Alberta, where he lived undetected in a lean-to in Fish Creek Provincial Park until he was arrested by the Calgary Police Service on July 6, 1985, after shooting security guard Sean Doyle in the hand while resisting arrest for stealing a can of salmon from the Hudson's Bay Department Store.[2][10] He was charged, and, in December 1985, convicted of shoplifting, assault with a weapon, and possession of a concealed firearm, and was sentenced to four and a half years in prison.[2] After serving his sentence, he remained incarcerated pending an extradition request from California authorities.[11]

Ng fought a protracted legal battle against extradition on the grounds that Canada, which did not have the death penalty for most offenses, would be violating the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms by permitting him to stand trial in California for capital murder. A habeas corpus petition and an Alberta Court of Appeal appeal were both denied. On September 26, 1991, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled by a vote of 4 to 3 against him. According to former Alberta prosecutor Scott Newark, Canada deported Ng to California 18 minutes after the ruling.[8]: 94 [12]

Murder trial

[edit]In Calaveras County, Ng was indicted on twelve counts of first-degree murder. After a change of venue to Orange County, he initiated a protracted series of pretrial motions. He sued the state over his temporary detainment at Folsom Prison, where he was caught hiding maps, fake IDs, and other escape paraphernalia, and filed challenges against four of the judges assigned to his case. He lodged a long series of complaints regarding the strength of his eyeglasses, the temperature of his food, and his right to practice origami in his jail cell.[13][failed verification]

Ng went through a total of 10 attorneys, some of whom ended up defending him a second time. He also filed a malpractice suit against several of the attorneys, citing incompetent representation.[13] After claiming that he had lost trust and confidence in all of his lawyers, he was allowed to represent himself, which delayed the trial another year while he researched applicable laws.[12] His trial finally began in October 1998, seven years after his extradition from Canada.

Balazs cooperated with investigators and received legal immunity from prosecution.[14] Court records stated that Balazs turned over weapons and other material to authorities during the investigation. Balazs was called a key witness in Ng's trial, but Ng's lawyer, William Kelley, in a surprise move, dismissed Balazs without asking any questions. Balazs was expected to shed light on what happened inside the mountain cabin that her parents owned. Kelley later declined to explain his actions.[14]

Despite the video evidence and information in Lake's voluminous diaries, Ng maintained that he was merely an observer and that Lake planned and committed all of the kidnappings, rapes, and murders unassisted.[7] He further maintained that he was dependent upon Lake for direction, that the abuse he suffered at the hands of his father was a mitigating factor, and that his good behavior behind bars showed that he should be imprisoned for life rather than executed.[9]

Psychiatrist Stuart Grassian testified that Ng had dependent personality disorder, but admitted under cross-examination that he had not viewed the tapes that showed Ng participating in the crimes. Clinical psychologist Abraham Nievod agreed with the diagnosis of dependent personality disorder and opined that Ng's behavior in the tapes indicated that he was attempting to "mirror" and please Lake. Four correctional officers, two sheriff's deputies, a prison library employee, and a prison counselor all testified that Ng was a model prisoner. Four former Marines who had known Ng while serving in the Marine Corps testified that he was quiet and well-behaved. Ng's parents testified about his troubled childhood and expressed remorse for their son's actions.[15]

Ng insisted on taking the stand in his own defense, which allowed prosecutors to introduce additional evidence that helped define Ng's role in all aspects of the crimes. One significant item was a photo of Ng in his prison cell, with cartoons he had sketched of his victims hanging on the wall behind him.[13]

At one point during the trial, Ng somehow managed to obtain the phone number of one of the jurors. He contacted the juror at home in an unsuccessful attempt to cause a mistrial.[citation needed] During the trial, he was kept in a metal cage within a room when not in the courtroom.

In February 1999, Ng was convicted of eleven of the twelve homicides: six men, three women, and two male infants. Jurors found him not guilty on the twelfth charge, the murder of Paul Cosner, even though Lake and Ng had driven Cosner's car for seven months since he went missing in November 1984, and Cosner's California driver's license had been found at the Wilseyville property. Ng was sentenced to death, and the presiding judge rejected a motion to reduce the sentence to life imprisonment. "Mr. Ng was not under any duress," he said, "nor does the evidence support that he was under the domination of Leonard Lake."[9] Ng's prosecution cost the State of California approximately $20 million, at the time the most expensive trial in the state's history.[4][16] It was twice as expensive as the O.J. Simpson trial in 1994–1995, which cost $9 million.[17] The victims which Ng was convicted of murdering were Sean Dubs, Deborah Dubs, Harvey Dubs, Clifford Peranteau, Jeffrey Gerald, Michael Carroll, Kathleen Allen, Lonnie Bond Sr, Lonnie Bond Jr, Robin Stapley and Brenda O'Connor, all of whom were killed between July 1984 to April 1985.[18]

On July 28, 2022, the California Supreme Court upheld Ng's death sentence and conviction. Ng still has other federal appeals in spite of a moratorium on the death penalty by Governor Gavin Newsom.[19]

As of 2023, Ng remains on death row[20] at California Medical Facility.[21] No executions have taken place in California since 2006.

See also

[edit]- List of death row inmates in the United States

- List of serial killers by number of victims

- List of serial killers in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ a b Welborn, Larry (2011-02-25). "O.C. death row: 11 murders, maybe more". The Register. Archived from the original on 2011-03-01. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ^ a b c "Ngs trail went from California to Calgary and back again". The Lethbridge Herald. Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada: Heritage Archives. 1998-11-12. p. A9. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ^ "Charles Ng Biography". biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Reference Re Ng Extradition". umontreal.ca. 1991-09-26. Archived from the original on 2010-01-17. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ "Charles Chi-tat Ng – Extradited From Canada to Face Death Penalty in California". Canadian Coalition Against the Death Penalty. 2005-04-25. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ^ YI, DANIEL (April 21, 1999). "Ng's Father Blames Self, Begs Jurors to Spare Son". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c "As Jury Meets to Decide His Fate, Ng Expects Death – latimes". Los Angeles Times. April 12, 1999. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Greig, Charlotte (2005). Evil Serial Killers: In the Minds of Monsters. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-7607-7566-0. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- ^ a b c d e World: "America's serial killer sentenced to die" Archived 2018-06-18 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, June 30, 1999. Accessed August 15, 2013.

- ^ Hickey, E.W. (2003). Encyclopedia of Murder and Violent Crime. SAGE Publications. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7619-2437-1. Archived from the original on 2015-05-25. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ Bishop, Katherine (1991-02-13). "Murder Suspect's Bid to Stay in Canada Tests Pact". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-05-25. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ a b "Charles Ng Has a Date With a Needle". San Francisco Chronicle. 1999-07-06. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ a b c Serial Killer Charles Ng – A Master of Legal Manipulation Archived 2017-03-24 at the Wayback Machine. ThoughtCo.com (March 1, 2016). Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Yi, Daniel (January 8, 1999). "Defense Seeks to Put Ng on Witness Stand". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Lasseter, Don (2000). Die for Me: The Terrifying True Story of the Charles Ng & Leonard Lake Torture Murders. Pinnacle Books. pp. 393–403. ISBN 978-0-7860-1107-0.

- ^ "Leonard Lake and Charles Ng". Frances Farmer's Revenge. Archived from the original on March 8, 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ "Simpson trial cost taxpayers $9-million". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ "People v. Charles Chitat Ng". casetext.

- ^ Thompson, Don (2022-07-28). "California court OKs death penalty in '80s sex slave murders". ABC News. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ CDCR Division of Adult Operations. "Death Row Tracking System – Condemned Inmate List" (PDF). California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-30. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- ^ CDCR (2024-03-24). "CDCR California Incarcerated Records and Information Search (CIRIS)". California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Retrieved 2024-03-24.

Further reading

[edit]- Owens, Gregg (2001). No Kill, No Thrill: The Shocking True Story of Charles Ng – One of North America's Most Horrific Serial Killers. Red Deer Press. ISBN 978-0-88995-209-6.

External links

[edit]- Charles Ng at IMDb

- Bellamy, Patrick. "Charles Ng: Cheating Death". truTV Crime Library. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2017. Crime Library's detailed accounts of Charles Ng and Leonard Lake's killing spree

- Chitat Ng v. Canada, Communication No. 469/1991, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/49/D/469/1991 (1994)

- Living people

- 1960 births

- 1984 murders in the United States

- 1985 murders in the United States

- 20th-century Chinese criminals

- Chinese expatriates in the United States

- Chinese male criminals

- Chinese people convicted of murder

- Chinese prisoners sentenced to death

- Hong Kong people with disabilities

- Hong Kong serial killers

- People convicted of murder by California

- People extradited from Canada to the United States

- People with personality disorders

- People convicted of desertion

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States military

- Prisoners sentenced to death by California

- Serial killers from California

- Torture in the United States

- United States Marines

- United States Marine Corps personnel who were court-martialed