Argentina

Argentine Republic[A] República Argentina (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

| Anthem: Himno Nacional Argentino ("Argentine National Anthem") | |

| Sol de Mayo[2] (Sun of May)  | |

Argentine territory in dark green; territory claimed but not controlled by Argentina in light green | |

| Capital and largest city | Buenos Aires 34°36′S 58°23′W / 34.600°S 58.383°W |

| Official languages | Spanish (de facto)[a] |

| Co-official languages | |

| Religion (2019)[7] |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Federal presidential republic |

| Javier Milei | |

| Victoria Villarruel | |

| Guillermo Francos | |

| Martín Menem | |

| Horacio Rosatti | |

| Legislature | National Congress |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Independence from Spain | |

| 25 May 1810 | |

• Declared | 9 July 1816 |

| 1 May 1853 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,780,400 km2 (1,073,500 sq mi)[B] (8th) |

• Water (%) | 1.57 |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• 2022 census | |

• Density | 16.6/km2 (43.0/sq mi)[8] (178th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (48th) |

| Currency | Argentine peso ($) (ARS) |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (ART) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| Drives on | right[b] |

| Calling code | +54 |

| ISO 3166 code | AR |

| Internet TLD | .ar |

Argentina,[a] officially the Argentine Republic,[b] is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of 2,780,400 km2 (1,073,500 sq mi),[B] making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourth-largest country in the Americas, and the eighth-largest country in the world. It shares the bulk of the Southern Cone with Chile to the west, and is also bordered by Bolivia and Paraguay to the north, Brazil to the northeast, Uruguay and the South Atlantic Ocean to the east, and the Drake Passage to the south. Argentina is a federal state subdivided into twenty-three provinces, and one autonomous city, which is the federal capital and largest city of the nation, Buenos Aires. The provinces and the capital have their own constitutions, but exist under a federal system. Argentina claims sovereignty over the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, and a part of Antarctica.

The earliest recorded human presence in modern-day Argentina dates back to the Paleolithic period.[14] The Inca Empire expanded to the northwest of the country in Pre-Columbian times. The country has its roots in Spanish colonization of the region during the 16th century.[15] Argentina rose as the successor state of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata,[16] a Spanish overseas viceroyalty founded in 1776. The declaration and fight for independence (1810–1818) was followed by an extended civil war that lasted until 1861, culminating in the country's reorganization as a federation. The country thereafter enjoyed relative peace and stability, with several waves of European immigration, mainly Italians and Spaniards, influencing its culture and demography.[17][18][19][20]

Following the death of President Juan Perón in 1974, his widow and vice president, Isabel Perón, ascended to the presidency, before being overthrown in 1976. The following military junta, which was supported by the United States, persecuted and murdered thousands of political critics, activists, and leftists in the Dirty War, a period of state terrorism and civil unrest that lasted until the election of Raúl Alfonsín as president in 1983.

Argentina is a regional power, and retains its historic status as a middle power in international affairs.[21][22][23] A major non-NATO ally of the United States,[24] Argentina is a developing country with the second-highest HDI (human development index) in Latin America after Chile.[25] It maintains the second-largest economy in South America, and is a member of G-15 and G20. Argentina is also a founding member of the United Nations, World Bank, World Trade Organization, Mercosur, Community of Latin American and Caribbean States and the Organization of Ibero-American States.

Etymology

The description of the region by the word Argentina has been found on a Venetian map in 1536.[26]

In English, the name Argentina comes from the Spanish language; however, the naming itself is not Spanish, but Italian. Argentina (masculine argentino) means in Italian '(made) of silver, silver coloured', derived from the Latin argentum for silver. In Italian, the adjective or the proper noun is often used in an autonomous way as a substantive and replaces it and it is said l'Argentina.

The name Argentina was probably first given by the Venetian and Genoese navigators, such as Giovanni Caboto. In Spanish and Portuguese, the words for 'silver' are respectively plata and prata and '(made) of silver' is plateado and prateado, although argento for 'silver' and argentado for 'covered in silver' exist in Spanish. Argentina was first associated with the silver mountains legend, widespread among the first European explorers of the La Plata Basin.[27]

The first written use of the name in Spanish can be traced to La Argentina,[C] a 1602 poem by Martín del Barco Centenera describing the region.[28] Although "Argentina" was already in common usage by the 18th century, the country was formally named "Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata" by the Spanish Empire, and "United Provinces of the Río de la Plata" after independence.

The 1826 constitution included the first use of the name "Argentine Republic" in legal documents.[29] The name "Argentine Confederation" was also commonly used and was formalized in the Argentine Constitution of 1853.[30] In 1860 a presidential decree settled the country's name as "Argentine Republic",[31] and that year's constitutional amendment ruled all the names since 1810 as legally valid.[32][D]

In English, the country was traditionally called "the Argentine", mimicking the typical Spanish usage la Argentina[33] and perhaps resulting from a mistaken shortening of the fuller name 'Argentine Republic'. 'The Argentine' fell out of fashion during the mid-to-late 20th century, and now the country is referred to as "Argentina".

History

Pre-Columbian era

The earliest traces of human life in the area now known as Argentina are dated from the Paleolithic period, with further traces in the Mesolithic and Neolithic.[14] Until the period of European colonization, Argentina was relatively sparsely populated by a wide number of diverse cultures with different social organizations,[34] which can be divided into three main groups.[35]

The first group are basic hunters and food gatherers without the development of pottery, such as the Selk'nam and Yaghan in the extreme south. The second group are advanced hunters and food gatherers which include the Puelche, Querandí and Serranos in the centre-east; and the Tehuelche in the south—all of them conquered by the Mapuche spreading from Chile[36]—and the Kom and Wichi in the north. The last group are farmers with pottery, such as the Charrúa, Minuane and Guaraní in the northeast, with slash and burn semisedentary existence;[34] the advanced Diaguita sedentary trading culture in the northwest, which was conquered by the Inca Empire around 1480; the Toconoté and Hênîa and Kâmîare in the country's centre, and the Huarpe in the centre-west, a culture that raised llama cattle and was strongly influenced by the Incas.[34]

Colonial era

Europeans first arrived in the region with the 1502 voyage of Amerigo Vespucci. The Spanish navigators Juan Díaz de Solís and Sebastian Cabot visited the territory that is now Argentina in 1516 and 1526, respectively.[15] In 1536 Pedro de Mendoza founded the small settlement of Buenos Aires, which was abandoned in 1541.[37]

Further colonization efforts came from Paraguay—establishing the Governorate of the Río de la Plata—Peru and Chile.[38] Francisco de Aguirre founded Santiago del Estero in 1553. Londres was founded in 1558; Mendoza, in 1561; San Juan, in 1562; San Miguel de Tucumán, in 1565.[39] Juan de Garay founded Santa Fe in 1573 and the same year Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera set up Córdoba.[40] Garay went further south to re-found Buenos Aires in 1580.[41] San Luis was established in 1596.[39]

The Spanish Empire subordinated the economic potential of the Argentine territory to the immediate wealth of the silver and gold mines in Bolivia and Peru, and as such it became part of the Viceroyalty of Peru until the creation of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776 with Buenos Aires as its capital.[42]

Buenos Aires repelled two ill-fated British invasions in 1806 and 1807.[43] The ideas of the Age of Enlightenment and the example of the first Atlantic Revolutions generated criticism of the absolutist monarchy that ruled the country. As in the rest of Spanish America, the overthrow of Ferdinand VII during the Peninsular War created great concern.[44]

Independence and civil wars

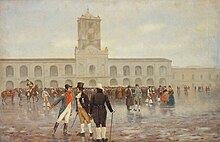

Beginning a process from which Argentina was to emerge as successor state to the Viceroyalty,[16] the 1810 May Revolution replaced the viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros with the First Junta, a new government in Buenos Aires made up from locals.[44] In the first clashes of the Independence War the Junta crushed a royalist counter-revolution in Córdoba,[46] but failed to overcome those of the Banda Oriental, Upper Peru and Paraguay, which later became independent states.[47] The French-Argentine Hippolyte Bouchard then brought his fleet to wage war against Spain overseas and attacked Spanish California, Spanish Peru and Spanish Philippines. He secured the allegiance of escaped Filipinos in San Blas who defected from the Spanish to join the Argentine navy, due to common Argentine and Philippine grievances against Spanish colonization.[48][49] Jose de San Martin's brother, Juan Fermín de San Martín, was already in the Philippines and drumming up revolutionary fervor prior to this.[50] At a later date, the Argentine sign of Inca origin, the Sun of May was adopted as a symbol by the Filipinos in the Philippine Revolution against Spain. He also secured the diplomatic recognition of Argentina from King Kamehameha I of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Historian Pacho O'Donnell affirms that Hawaii was the first state that recognized Argentina's independence.[51]He was finally arrested in 1819 by Chilean patriots.

Revolutionaries split into two antagonist groups: the Centralists and the Federalists—a move that would define Argentina's first decades of independence.[52] The Assembly of the Year XIII appointed Gervasio Antonio de Posadas as Argentina's first Supreme Director.[52]

On 9 July 1816, the Congress of Tucumán formalized the Declaration of Independence,[53] which is now celebrated as Independence Day, a national holiday.[54] One year later General Martín Miguel de Güemes stopped royalists on the north, and General José de San Martín. He joined Bernardo O'Higgins and they led a combined army across the Andes and secured the independence of Chile; then it was sent by O'Higgins orders to the Spanish stronghold of Lima and proclaimed the independence of Peru.[55][E] In 1819 Buenos Aires enacted a centralist constitution that was soon abrogated by federalists.[57]

Some of the most important figures of Argentine independence made a proposal known as the Inca plan of 1816, which proposed that the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (Present Argentina) should be a monarchy, led by a descendant of the Inca. Juan Bautista Túpac Amaru (half-brother of Túpac Amaru II) was proposed as monarch.[58] Some examples of those who supported this proposal were Manuel Belgrano, José de San Martín and Martín Miguel de Güemes. The Congress of Tucumán finally decided to reject the Inca plan, creating instead a republican, centralist state.[59][60]

The 1820 Battle of Cepeda, fought between the Centralists and the Federalists, resulted in the end of the Supreme Director rule. In 1826 Buenos Aires enacted another centralist constitution, with Bernardino Rivadavia being appointed as the first president of the country. However, the interior provinces soon rose against him, forced his resignation and discarded the constitution.[61] Centralists and Federalists resumed the civil war; the latter prevailed and formed the Argentine Confederation in 1831, led by Juan Manuel de Rosas.[62] During his regime he faced a French blockade (1838–1840), the War of the Confederation (1836–1839), and an Anglo-French blockade (1845–1850), but remained undefeated and prevented further loss of national territory.[63] His trade restriction policies, however, angered the interior provinces and in 1852 Justo José de Urquiza, another powerful caudillo, beat him out of power. As the new president of the Confederation, Urquiza enacted the liberal and federal 1853 Constitution. Buenos Aires seceded but was forced back into the Confederation after being defeated in the 1859 Battle of Cepeda.[64]

Rise of the modern nation

Overpowering Urquiza in the 1861 Battle of Pavón, Bartolomé Mitre secured Buenos Aires' predominance and was elected as the first president of the reunified country. He was followed by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento and Nicolás Avellaneda; these three presidencies set up the basis of the modern Argentine State.[65]

Starting with Julio Argentino Roca in 1880, ten consecutive federal governments emphasized liberal economic policies. The massive wave of European immigration they promoted—second only to the United States'—led to a near-reinvention of Argentine society and economy that by 1908 had placed the country as the seventh wealthiest[66] developed nation[67] in the world. Driven by this immigration wave and decreasing mortality, the Argentine population grew fivefold and the economy 15-fold:[68] from 1870 to 1910, Argentina's wheat exports went from 100,000 to 2,500,000 t (110,000 to 2,760,000 short tons) per year, while frozen beef exports increased from 25,000 to 365,000 t (28,000 to 402,000 short tons) per year,[69] placing Argentina as one of the world's top five exporters.[70] Its railway mileage rose from 503 to 31,104 km (313 to 19,327 mi).[71] Fostered by a new public, compulsory, free and secular education system, literacy quickly increased from 22% to 65%, a level higher than most Latin American nations would reach even fifty years later.[70] Furthermore, real GDP grew so fast that despite the huge immigration influx, per capita income between 1862 and 1920 went from 67% of developed country levels to 100%:[71] In 1865, Argentina was already one of the top 25 nations by per capita income. By 1908, it had surpassed Denmark, Canada and the Netherlands to reach 7th place—behind Switzerland, New Zealand, Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom and Belgium. Argentina's per capita income was 70% higher than Italy's, 90% higher than Spain's, 180% higher than Japan's and 400% higher than Brazil's.[66] Despite these unique achievements, the country was slow to meet its original goals of industrialization:[72] after the steep development of capital-intensive local industries in the 1920s, a significant part of the manufacturing sector remained labour-intensive in the 1930s.[73]

Between 1878 and 1884, the so-called Conquest of the Desert occurred, with the purpose of tripling the Argentine territory by means of the constant confrontations between natives and Criollos in the border,[75] and the appropriation of the indigenous territories. The first conquest consisted of a series of military incursions into the Pampa and Patagonian territories dominated by the indigenous peoples,[76] distributing them among the members of the Sociedad Rural Argentina, financiers of the expeditions.[77] The conquest of Chaco lasted up to the end of the century,[78] since its full ownership of the national economic system only took place when the mere extraction of wood and tannin was replaced by the production of cotton.[79] The Argentine government considered indigenous people as inferior beings, without the same rights as Criollos and Europeans.[80]

In 1912, President Roque Sáenz Peña enacted universal and secret male suffrage, which allowed Hipólito Yrigoyen, leader of the Radical Civic Union (or UCR), to win the 1916 election. He enacted social and economic reforms and extended assistance to small farms and businesses. Argentina stayed neutral during World War I. The second administration of Yrigoyen faced an economic crisis, precipitated by the Great Depression.[81]

In 1930, Yrigoyen was ousted from power by the military led by José Félix Uriburu. Although Argentina remained among the fifteen richest countries until mid-century,[66] this coup d'état marks the start of the steady economic and social decline that pushed the country back into underdevelopment.[82]

Uriburu ruled for two years; then Agustín Pedro Justo was elected in a fraudulent election, and signed a controversial treaty with the United Kingdom. Argentina stayed neutral during World War II, a decision that had full British support but was rejected by the United States after the attack on Pearl Harbor. In 1943 a military coup d'état led by General Arturo Rawson toppled the democratically elected government of Ramón Castillo. Under pressure from the United States, later Argentina declared war on the Axis Powers (on 27 March 1945, roughly a month before the end of World War II in Europe).

During the Rawson dictatorship a relatively unknown military colonel named Juan Perón was named head of the Labour Department. Perón quickly managed to climb the political ladder, being named Minister of Defence by 1944. Being perceived as a political threat by rivals in the military and the conservative camp, he was forced to resign in 1945, and was arrested days later. He was finally released under mounting pressure from both his base and several allied unions.[83] He would later become president after a landslide victory over the UCR in the 1946 general election as the Laborioust candidate.[84]

Peronist years

The Labour Party (later renamed Justicialist Party), the most powerful and influential party in Argentine history, came into power with the rise of Juan Perón to the presidency in 1946. He nationalized strategic industries and services, improved wages and working conditions, paid the full external debt and claimed he achieved nearly full employment. He pushed Congress to enact women's suffrage in 1947,[85] and developed a system of social assistance for the most vulnerable sectors of society.[86] The economy began to decline in 1950 due in part to government expenditures and the protectionist economic policies.[87]

He also engaged in a campaign of political suppression. Anyone who was perceived to be a political dissident or potential rival was subject to threats, physical violence and harassment. The Argentine intelligentsia, the middle-class, university students, and professors were seen as particularly troublesome. Perón fired over 2,000 university professors and faculty members from all major public education institutions.[88]

Perón tried to bring most trade and labour unions under his thumb, regularly resorting to violence when needed. For instance, the meat-packers union leader, Cipriano Reyes, organized strikes in protest against the government after elected labour movement officials were forcefully replaced by Peronist puppets from the Peronist Party. Reyes was soon arrested on charges of terrorism, though the allegations were never substantiated. Reyes, who was never formally charged, was tortured in prison for five years and only released after the regime's downfall in 1955.[89]

Perón managed to get re-elected in 1951. His wife Eva Perón, who played a critical role in the party, died of cancer in 1952. As the economy continued to tank, Perón started losing popular support, and came to be seen as a threat to the national process. The Navy took advantage of Perón's withering political power, and bombed the Plaza de Mayo in 1955. Perón survived the attack, but a few months later, during the Liberating Revolution coup, he was deposed and went into exile in Spain.[90]

Revolución Libertadora

The new head of State, Pedro Eugenio Aramburu, proscribed Peronism and banned the party from any future elections. Arturo Frondizi from the UCR won the 1958 general election.[91] He encouraged investment to achieve energetic and industrial self-sufficiency, reversed a chronic trade deficit and lifted the ban on Peronism; yet his efforts to stay on good terms with both the Peronists and the military earned him the rejection of both and a new coup forced him out.[92] Amidst the political turmoil, Senate leader José María Guido reacted swiftly and applied anti-power vacuum legislation, ascending to the presidency himself; elections were repealed and Peronism was prohibited once again. Arturo Illia was elected in 1963 and led an increase in prosperity across the board; however he was overthrown in 1966 by another military coup d'état led by General Juan Carlos Onganía in the self-proclaimed Argentine Revolution, creating a new military government that sought to rule indefinitely.[93]

Perón's return and death

Following several years of military rule, Alejandro Agustín Lanusse was appointed president by the military junta in 1971. Under increasing political pressure for the return of democracy, Lanusse called for elections in 1973. Perón was banned from running but the Peronist party was allowed to participate. The presidential elections were won by Perón's surrogate candidate, Hector Cámpora, a left-wing Peronist, who took office on 25 May 1973. A month later, in June, Perón returned from Spain. One of Cámpora's first presidential actions was to grant amnesty to members of organizations that had carried out political assassinations and terrorist attacks, and to those who had been tried and sentenced to prison by judges. Cámpora's months-long tenure in government was beset by political and social unrest. Over 600 social conflicts, strikes, and factory occupations took place within a single month.[94] Even though far-left terrorist organisations had suspended their armed struggle, their joining with the participatory democracy process was interpreted as a direct threat by the Peronist right-wing faction.[95]

Amid a state of political, social, and economic upheaval, Cámpora and Vice President Vicente Solano Lima resigned in July 1973, calling for new elections, but this time with Perón as the Justicialist Party nominee. Perón won the election with his wife Isabel Perón as vice president. Perón's third term was marked by escalating conflict between left and right-wing factions within the Peronist party, as well as the return of armed terror guerrilla groups such as the Guevarist ERP, leftist Peronist Montoneros, and the state-backed far-right Triple A. After a series of heart attacks and signs of pneumonia in 1974, Perón's health deteriorated quickly. He suffered a final heart attack on Monday, 1 July 1974, and died at 13:15. He was 78 years old. After his death, Isabel Perón, his wife and vice president, succeeded him in office. During her presidency, a military junta, along with the Peronists' far-right fascist faction, once again became the de facto head of state. Isabel Perón served as President of Argentina from 1974 until 1976, when she was ousted by the military. Her short presidency was marked by the collapse of Argentine political and social systems, leading to a constitutional crisis that paved the way for a decade of instability, left-wing terrorist guerrilla attacks, and state-sponsored terrorism.[87][96][97]

National Reorganization Process

The "Dirty War" (Spanish: Guerra Sucia) was part of Operation Condor, which included the participation of other right-wing dictatorships in the Southern Cone. The Dirty War involved state terrorism in Argentina and elsewhere in the Southern Cone against political dissidents, with military and security forces employing urban and rural violence against left-wing guerrillas, political dissidents, and anyone believed to be associated with socialism or somehow contrary to the neoliberal economic policies of the regime.[98][99][100] Victims of the violence in Argentina alone included an estimated 15,000 to 30,000 left-wing activists and militants, including trade unionists, students, journalists, Marxists, Peronist guerrillas,[101] and alleged sympathizers. Most of the victims were casualties of state terrorism. The opposing guerrillas' victims numbered nearly 500–540 military and police officials[102] and up to 230 civilians.[103] Argentina received technical support and military aid from the United States government during the Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Reagan administrations.

The exact chronology of the repression is still debated, yet the roots of the long political war may have started in 1969 when trade unionists were targeted for assassination by Peronist and Marxist paramilitaries. Individual cases of state-sponsored terrorism against Peronism and the left can be traced back even further to the Bombing of Plaza de Mayo in 1955. The Trelew massacre of 1972, the actions of the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance commencing in 1973, and Isabel Perón's "annihilation decrees" against left-wing guerrillas during Operativo Independencia (Operation Independence) in 1975, are also possible events signaling the beginning of the Dirty War.[F]

Onganía shut down Congress, banned all political parties, and dismantled student and worker unions. In 1969, popular discontent led to two massive protests: the Cordobazo and the Rosariazo. The terrorist guerrilla organization Montoneros kidnapped and executed Aramburu.[107] The newly chosen head of government, Alejandro Agustín Lanusse, seeking to ease the growing political pressure, allowed Héctor José Cámpora to become the Peronist candidate instead of Perón. Cámpora won the March 1973 election, issued pardons for condemned guerrilla members, and then secured Perón's return from his exile in Spain.[108]

On the day Perón returned to Argentina, the clash between Peronist internal factions—right-wing union leaders and left-wing youth from the Montoneros—resulted in the Ezeiza Massacre. Overwhelmed by political violence, Cámpora resigned and Perón won the following September 1973 election with his third wife Isabel as vice-president. He expelled Montoneros from the party[109] and they became once again a clandestine organization. José López Rega organized the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (AAA) to fight against them and the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP).[110][111]

Perón died in July 1974 and was succeeded by his wife, who signed a secret decree empowering the military and the police to "annihilate" the left-wing subversion,[112] stopping ERP's attempt to start a rural insurgence in Tucumán province.[113] Isabel Perón was ousted one year later by a junta of the combined armed forces, led by army general Jorge Rafael Videla. They initiated the National Reorganization Process, often shortened to Proceso.[114]

The Proceso shut down Congress, removed the judges on the Supreme Court, banned political parties and unions, and resorted to employing the forced disappearance of suspected guerrilla members including individuals suspected of being associated with the left-wing. By the end of 1976, the Montoneros had lost nearly 2,000 members and by 1977, the ERP was completely subdued. Nevertheless, the severely weakened Montoneros launched a counterattack in 1979, which was quickly put down, effectively ending the guerrilla threat and securing the junta's position in power.[citation needed]

In March 1982, an Argentine force took control of the British territory of South Georgia and, on 2 April, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands. The United Kingdom dispatched a task force to regain possession. Argentina surrendered on 14 June and its forces were taken home. Street riots in Buenos Aires followed the humiliating defeat and the military leadership stood down.[115][116] Reynaldo Bignone replaced Galtieri and began to organize the transition to democratic governance.[117]

Return to democracy

Raúl Alfonsín won the 1983 elections campaigning for the prosecution of those responsible for human rights violations during the Proceso: the Trial of the Juntas and other martial courts sentenced all the coup's leaders but, under military pressure, he also enacted the Full Stop and Due Obedience laws,[118][119] which halted prosecutions further down the chain of command. The worsening economic crisis and hyperinflation reduced his popular support and the Peronist Carlos Menem won the 1989 election. Soon after, riots forced Alfonsín to an early resignation.[120]

Menem embraced and enacted neoliberal policies:[121] a fixed exchange rate, business deregulation, privatizations, and the dismantling of protectionist barriers normalized the economy in the short term. He pardoned the officers who had been sentenced during Alfonsín's government. The 1994 Constitutional Amendment allowed Menem to be elected for a second term. With the economy beginning to decline in 1995, and with increasing unemployment and recession,[122] the UCR, led by Fernando de la Rúa, returned to the presidency in the 1999 elections.[123]

De la Rúa left Menem's economic plan in effect despite the worsening crisis, which led to growing social discontent.[122] Massive capital flight from the country was responded to with a freezing of bank accounts, generating further turmoil. The December 2001 riots forced him to resign.[124] Congress appointed Eduardo Duhalde as acting president, who revoked the fixed exchange rate established by Menem,[125] causing many working- and middle-class Argentines to lose a significant portion of their savings. By late 2002, the economic crisis began to recede, but the assassination of two piqueteros by the police caused political unrest, prompting Duhalde to move elections forward.[126] Néstor Kirchner was elected as the new president. On 26 May 2003, he was sworn in.[127][128]

Boosting the neo-Keynesian economic policies[126] laid by Duhalde, Kirchner ended the economic crisis attaining significant fiscal and trade surpluses, and rapid GDP growth.[129] Under his administration, Argentina restructured its defaulted debt with an unprecedented discount of about 70% on most bonds, paid off debts with the International Monetary Fund,[130] purged the military of officers with dubious human rights records,[131] nullified and voided the Full Stop and Due Obedience laws,[132][G] ruled them as unconstitutional, and resumed legal prosecution of the Junta's crimes. He did not run for reelection, promoting instead the candidacy of his wife, senator Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who was elected in 2007[134] and reelected in 2011. Fernández de Kirchner's administration established positive foreign relations with countries such as Venezuela, Iran, and Cuba, while at the same time relations with the United States and the United Kingdom became increasingly strained. By 2015, the Argentine GDP grew by 2.7%[135] and real incomes had risen over 50% since the post-Menem era.[136] Despite these economic gains and increased renewable energy production and subsidies, the overall economy had been sluggish since 2011.[137]

On 22 November 2015, after a tie in the first round of presidential elections on 25 October, center-right coalition candidate Mauricio Macri won the first ballotage in Argentina's history, beating Front for Victory candidate Daniel Scioli and becoming president-elect.[138] Macri was the first democratically elected non-peronist president since 1916 that managed to complete his term in office without being overthrown.[139] He took office on 10 December 2015 and inherited an economy with a high inflation rate and in a poor shape.[140] In April 2016, the Macri Government introduced neoliberal austerity measures intended to tackle inflation and overblown public deficits.[141] Under Macri's administration, economic recovery remained elusive with GDP shrinking 3.4%, inflation totaling 240%, billions of US dollars issued in sovereign debt, and mass poverty increasing by the end of his term.[142][143] He ran for re-election in 2019 but lost by nearly eight percentage points to Alberto Fernández, the Justicialist Party candidate.[144]

President Alberto Fernández and Vice President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner took office in December 2019,[145] just months before the COVID-19 pandemic hit Argentina and among accusations of corruption, bribery and misuse of public funds during Nestor and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner's presidencies.[146][147] On 14 November 2021, the center-left coalition of Argentina's ruling Peronist party, Frente de Todos (Front for Everyone), lost its majority in Congress, for the first time in almost 40 years, in midterm legislative elections. The election victory of the center-right coalition, Juntos por el Cambio (Together for Change) limited President Alberto Fernandez's power during his final two years in office. Losing control of the Senate made it difficult for him to make key appointments, including to the judiciary. It also forced him to negotiate with the opposition every initiative he sends to the legislature.[148][149]

In April 2023, President Alberto Fernandez announced that he will not seek re-election in the next presidential election.[150] The 19 November 2023 election run-off vote ended in a win for libertarian outsider Javier Milei with close to 56% of the vote against 44% of the ruling coalition candidate Sergio Massa.[151] On 10 December 2023, Javier Milei was sworn in as the new president of Argentina.[152]

Geography

With a mainland surface area of 2,780,400 km2 (1,073,518 sq mi),[B] Argentina is located in southern South America, sharing land borders with Chile across the Andes to the west;[153] Bolivia and Paraguay to the north; Brazil to the northeast, Uruguay and the South Atlantic Ocean to the east;[154] and the Drake Passage to the south;[155] for an overall land border length of 9,376 km (5,826 mi). Its coastal border over the Río de la Plata and South Atlantic Ocean is 5,117 km (3,180 mi) long.[154]

Argentina's highest point is Aconcagua in the Mendoza province (6,959 m (22,831 ft) above sea level),[156] also the highest point in the Southern and Western Hemispheres.[157] The lowest point is Laguna del Carbón in the San Julián Great Depression Santa Cruz province (−105 m (−344 ft) below sea level,[156] also the lowest point in the Southern and Western Hemispheres, and the seventh lowest point on Earth).[158]

The northernmost point is at the confluence of the Grande de San Juan and Mojinete rivers in Jujuy province; the southernmost is Cape San Pío in Tierra del Fuego province; the easternmost is northeast of Bernardo de Irigoyen, Misiones and the westernmost is within Los Glaciares National Park in Santa Cruz province.[154] The maximum north–south distance is 3,694 km (2,295 mi), while the maximum east–west one is 1,423 km (884 mi).[154]

Some of the major rivers are the Paraná, Uruguay—which join to form the Río de la Plata, Paraguay, Salado, Negro, Santa Cruz, Pilcomayo, Bermejo and Colorado.[159] These rivers are discharged into the Argentine Sea, the shallow area of the Atlantic Ocean over the Patagonian Shelf, an unusually wide continental platform.[160] Its waters are influenced by two major ocean currents: the warm Brazil Current and the cold Falklands Current.[161]

Biodiversity

Argentina is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world[163] hosting one of the greatest ecosystem varieties in the world: 15 continental zones, 2 marine zones, and the Antarctic region are all represented in its territory.[163] This huge ecosystem variety has led to a biological diversity that is among the world's largest:[163][164] 9,372 cataloged vascular plant species (ranked 24th);[H] 1,038 cataloged bird species (ranked 14th);[I] 375 cataloged mammal species (ranked 12th);[J] 338 cataloged reptilian species (ranked 16th); and 162 cataloged amphibian species (ranked 19th).

In Argentina forest cover is around 10% of the total land area, equivalent to 28,573,000 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, down from 35,204,000 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 27,137,000 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 1,436,000 hectares (ha). Of the naturally regenerating forest 0% was reported to be primary forest (consisting of native tree species with no clearly visible indications of human activity) and around 7% of the forest area was found within protected areas. For the year 2015, 0% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership, 4% private ownership and 96% with ownership listed as other or unknown.[165][166]

The original pampa had virtually no trees; some imported species such as the American sycamore or eucalyptus are present along roads or in towns and country estates (estancias). The only tree-like plant native to the pampa is the evergreen Ombú. The surface soils of the pampa are a deep black color, primarily mollisols, known commonly as humus. This makes the region one of the most agriculturally productive on Earth; however, this is also responsible for decimating much of the original ecosystem, to make way for commercial agriculture.[citation needed] The western pampas receive less rainfall, this dry pampa is a plain of short grasses or steppe.[167][168]

The National Parks of Argentina make up a network of 35 national parks in Argentina. The parks cover a very varied set of terrains and biotopes, from Baritú National Park on the northern border with Bolivia to Tierra del Fuego National Park in the far south of the continent. The Administración de Parques Nacionales (National Parks Administration) is the agency that preserves and manages these national parks along with Natural monuments and National Reserves within the country.[169] Argentina had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.21/10, ranking it 47th globally out of 172 countries.[170]

Climate

In general, Argentina has four main climate types: warm humid subtropical, moderate humid subtropical, arid, and cold, all determined by the expanse across latitude, range in altitude, and relief features.[172][173] Although the most populated areas are generally temperate, Argentina has an exceptional amount of climate diversity,[174] ranging from subtropical in the north to polar in the far south.[175] Consequently, there is a wide variety of biomes in the country, including Subtropical rainforests, semi-arid and arid regions, temperate plains in the Pampas, and cold subantarctic in the south.[176] The average annual precipitation ranges from 150 millimetres (6 in) in the driest parts of Patagonia to over 2,000 millimetres (79 in) in the westernmost parts of Patagonia and the northeastern parts of the country.[174] Mean annual temperatures range from 5 °C (41 °F) in the far south to 25 °C (77 °F) in the north.[174]

Major wind currents include the cool Pampero Winds blowing on the flat plains of Patagonia and the Pampas; following the cold front, warm currents blow from the north in middle and late winter, creating mild conditions.[177] The Sudestada usually moderates cold temperatures but brings very heavy rains, rough seas and coastal flooding. It is most common in late autumn and winter along the central coast and in the Río de la Plata estuary.[177] The Zonda, a hot dry wind, affects Cuyo and the central Pampas. Squeezed of all moisture during the 6,000 m (19,685 ft) descent from the Andes, Zonda winds can blow for hours with gusts up to 120 km/h (75 mph), fueling wildfires and causing damage; between June and November, when the Zonda blows, snowstorms and blizzard (viento blanco) conditions usually affect higher elevations.[178]

Climate change in Argentina is predicted to have significant effects on the living conditions in Argentina.[179]: 30 The climate of Argentina is changing with regards to precipitation patterns and temperatures. The highest increases in precipitation (from the period 1960–2010) have occurred in the eastern parts of the country. The increase in precipitation has led to more variability in precipitation from year to year in the northern parts of the country, with a higher risk of prolonged droughts, disfavoring agriculture in these regions.

Politics

In the 20th century, Argentina experienced significant political turmoil and democratic reversals.[180][181] Between 1930 and 1976, the armed forces overthrew six governments in Argentina;[181] and the country alternated periods of democracy (1912–1930, 1946–1955, and 1973–1976) with periods of restricted democracy and military rule.[180] Following a transition that began in 1983,[182] full-scale democracy in Argentina was reestablished.[180][181] Argentina's democracy endured through the 2001–02 crisis and to the present day; it is regarded as more robust than both its pre-1983 predecessors and other democracies in Latin America.[181] According to the V-Dem Democracy indices, Argentina in 2023 was the second most electoral democratic country in Latin America.[183]

Government

Argentina is a federal constitutional republic and representative democracy.[185] The government is regulated by a system of checks and balances defined by the Constitution of Argentina, the country's supreme legal document. The seat of government is the city of Buenos Aires, as designated by Congress.[186] Suffrage is universal, equal, secret and mandatory.[187][K]

The federal government is composed of three branches. The Legislative branch consists of the bicameral Congress, made up of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. The Congress makes federal law, declares war, approves treaties and has the power of the purse and of impeachment, by which it can remove sitting members of the government.[189] The Chamber of Deputies represents the people and has 257 voting members elected to a four-year term. Seats are apportioned among the provinces by population every tenth year.[190] As of 2014[update] ten provinces have just five deputies while the Buenos Aires Province, being the most populous one, has 70. The Chamber of Senators represents the provinces, and has 72 members elected at-large to six-year terms, with each province having three seats; one-third of Senate seats are up for election every other year.[191] At least one-third of the candidates presented by the parties must be women.

In the Executive branch, the President is the commander-in-chief of the military, can veto legislative bills before they become law—subject to Congressional override—and appoints the members of the Cabinet and other officers, who administer and enforce federal laws and policies.[192] The President is elected directly by the vote of the people, serves a four-year term and may be elected to office no more than twice in a row.[193]

The Judicial branch includes the Supreme Court and lower federal courts interpret laws and overturn those they find unconstitutional.[194] The Judicial is independent of the Executive and the Legislative. The Supreme Court has seven members appointed by the President—subject to Senate approval—who serve for life. The lower courts' judges are proposed by the Council of Magistracy (a secretariat composed of representatives of judges, lawyers, researchers, the Executive and the Legislative), and appointed by the president on Senate approval.[195]

Provinces

Argentina is a federation of twenty-three provinces and one autonomous city, Buenos Aires. Provinces are divided for administration purposes into departments and municipalities, except for Buenos Aires Province, which is divided into partidos. The City of Buenos Aires is divided into communes.

Provinces hold all the power that they chose not to delegate to the federal government;[196] they must be representative republics and must not contradict the Constitution.[197] Beyond this they are fully autonomous: they enact their own constitutions,[198] freely organize their local governments,[199] and own and manage their natural and financial resources.[200] Some provinces have bicameral legislatures, while others have unicameral ones.[L]

La Pampa and Chaco became provinces in 1951. Misiones did so in 1953, and Formosa, Neuquén, Río Negro, Chubut and Santa Cruz, in 1955. The last national territory, Tierra del Fuego, became the Tierra del Fuego, Antártida e Islas del Atlántico Sur Province in 1990.[202] It has three components, although two are nominal because they are not under Argentine sovereignty. The first is the Argentine part of Tierra del Fuego; the second is an area of Antarctica claimed by Argentina that overlaps with similar areas claimed by the UK and Chile; the third comprises the two disputed British Overseas Territories of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.[203]

Foreign relations

Foreign policy is handled by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Worship, which answers to the President. The country is one of the G-15 and G-20 major economies of the world, and a founding member of the UN, WBG, WTO and OAS. In 2012 Argentina was elected again to a two-year non-permanent position on the United Nations Security Council and is participating in major peacekeeping operations in Haiti, Cyprus, Western Sahara and the Middle East.[204] Argentina is described as a middle power.[21][205]

A prominent Latin American[22] and Southern Cone[23] regional power, Argentina co-founded OEI and CELAC. It is also a founding member of the Mercosur block, having Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela as partners. Since 2002 the country has emphasized its key role in Latin American integration, and the block—which has some supranational legislative functions—is its first international priority.[206]

Argentina claims 965,597 km2 (372,819 sq mi) in Antarctica, where it has the world's oldest continuous state presence, since 1904.[207] This overlaps claims by Chile and the United Kingdom, though all such claims fall under the provisions of the 1961 Antarctic Treaty, of which Argentina is a founding signatory and permanent consulting member, with the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat being based in Buenos Aires.[208]

Argentina disputes sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Spanish: Islas Malvinas), and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands,[209] which are administered by the United Kingdom as Overseas Territories. Argentina is a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[210] Argentina is a Major non-NATO ally since 1998[24] and an OECD candidate country since January 2022.[211]

Armed forces

The president holds the title of commander-in-chief of the Argentine Armed Forces, as part of a legal framework that imposes a strict separation between national defense and internal security systems:[212][213] The National Defense System, an exclusive responsibility of the federal government,[214] coordinated by the Ministry of Defense, and comprising the Army, the Navy and the Air Force.[215] Ruled and monitored by Congress[216] through the Houses' Defense Committees,[217] it is organized on the essential principle of legitimate self-defense: the repelling of any external military aggression in order to guarantee freedom of the people, national sovereignty, and territorial integrity.[217] Its secondary missions include committing to multinational operations within the framework of the United Nations, participating in internal support missions, assisting friendly countries, and establishing a sub-regional defense system.[217]

Military service is voluntary, with enlistment age between 18 and 24 years old and no conscription.[218] Argentina's defense has historically been one of the best equipped in the region, even managing its own weapon research facilities, shipyards, ordnance, tank and plane factories.[219] However, real military expenditures declined steadily after the defeat in the Falklands/Malvinas War and the defense budget in 2011 was only about 0.74% of GDP, a historical minimum,[220] below the Latin American average. Within the defence budget itself, funding for training and even basic maintenance has been significantly cut, a factor contributing to the accidental loss of the Argentine submarine San Juan in 2017. The result has been a steady erosion of Argentine military capabilities, with some arguing that Argentina had, by the end of the 2010s, ceased to be a capable military power.[221]

The Interior Security System is jointly administered by the federal and subscribing provincial governments.[213] At the federal level it is coordinated by the Interior, Security and Justice ministries, and monitored by Congress.[213] It is enforced by the Federal Police; the Prefecture, which fulfills coast guard duties; the Gendarmerie, which serves border guard tasks; and the Airport Security Police.[222] At the provincial level it is coordinated by the respective internal security ministries and enforced by local police agencies.[213]

Argentina was the only South American country to send warships and cargo planes in 1991 to the Gulf War under UN mandate and has remained involved in peacekeeping efforts in multiple locations such as UNPROFOR in Croatia/Bosnia, Gulf of Fonseca, UNFICYP in Cyprus (where among Army and Marines troops the Air Force provided the UN Air contingent since 1994) and MINUSTAH in Haiti. Argentina is the only Latin American country to maintain troops in Kosovo during SFOR (and later EUFOR) operations where combat engineers of the Argentine Armed Forces are embedded in an Italian brigade.

In 2007, an Argentine contingent including helicopters, boats and water purification plants was sent to help Bolivia against their worst floods in decades.[223] In 2010 the Armed Forces were also involved in Haiti and Chile humanitarian responses after their respective earthquakes.

Economy

Benefiting from rich natural resources, a highly literate population, a diversified industrial base, and an export-oriented agricultural sector, the economy of Argentina is Latin America's third-largest,[224] and the second-largest in South America.[225] Argentina was one of the richest countries in the world, on the 20th century in 1913 it was one of the wealthiest countries in the world by GDP per capita[226] It has a "very high" rating on the Human Development Index[13] and ranks 66th by nominal GDP per capita,[227] with a considerable internal market size and a growing share of the high-tech sector. As a middle emerging economy and one of the world's top developing nations, it is a member of the G-20 major economies.[228][M]

Argentina is the largest producer in the world of yerba-maté (due to the large domestic consumption of maté), one of the five largest producers in the world of soybeans, maize, sunflower seed, lemon and pear, one of the ten largest producers in the world of barley, grape, artichoke, tobacco and cotton, and one of the 15 largest producers in the world of wheat, sugarcane, sorghum and grapefruit. It is the largest producer in South America of wheat, sunflower seed, barley, lemon and pear.[230][231] In wine, Argentina is usually among the ten largest producers in the world.[232] Argentina is also a traditional meat exporter, having been, in 2019, the 4th world producer of beef, with a production of 3 million tons (only behind US, Brazil and China), the 4th world producer of honey, and the 10th world producer of wool, in addition to other relevant productions.[233][234]

The mining industry of Argentina is not as relevant as that of other countries. It stands out for being the fourth-largest producer of lithium,[235] 9th of silver[236] and 17th of gold[237] The country stands out in the production of natural gas, being the largest producer in South America and the 18th-largest in the world, and has an average annual production close to 500 thousand barrels/day of petroleum, even with the under-utilization of the Vaca Muerta field, due to the country's technical and financial inability to extract these resources.[238][239]

In 2012[update], manufacturing accounted for 20.3% of GDP—the largest sector in the nation's economy.[240] Well-integrated into Argentine agriculture, half of the industrial exports have rural origin.[240] With a 6.5% production growth rate in 2011[update],[241] the diversified manufacturing sector rests on a steadily growing network of industrial parks (314 as of 2013[update])[242][243] In 2012[update] the leading sectors by volume were: food processing, beverages and tobacco products; motor vehicles and auto parts; textiles and leather; refinery products and biodiesel; chemicals and pharmaceuticals; steel, aluminum and iron; industrial and farm machinery; home appliances and furniture; plastics and tires; glass and cement; and recording and print media.[240] In addition, Argentina has since long been one of the top five wine-producing countries in the world.[240]

High inflation—a weakness of the Argentine economy for decades—has become a trouble once again,[244] with an annual rate of 24.8% in 2017.[245] In 2023 the inflation reached 102.5% among the highest inflation rates in the world.[246] Approximately 43% of the Argentina's population lives below the poverty line as of 2023.[247] To deter it and support the peso, the government imposed foreign currency control.[248] Income distribution, having improved since 2002, is classified as "medium", although it is still considerably unequal.[12] In January 2024, Argentina's poverty rate reached 57.4%, the highest poverty rate in the country since 2004.[249]

Argentina ranks 85th out of 180 countries in the Transparency International's 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index,[250] an improvement of 22 positions over its 2014 rankings.[251] Argentina settled its long-standing debt default crisis in 2016 with the so-called vulture funds after the election of Mauricio Macri, allowing Argentina to enter capital markets for the first time in a decade.[252] The government of Argentina defaulted on 22 May 2020 by failing to pay a $500 million bill by its due date to its creditors. Negotiations for the restructuring of $66 billion of its debt continue.[253]

Poverty in Argentina was 41.7 percent at the end of the second half of 2023.[254]

Tourism

The country had 5.57 million visitors in 2013, ranking in terms of international tourist arrivals as the top destination in South America, and second in Latin America after Mexico.[255] Revenues from international tourists reached US$4.41 billion in 2013, down from US$4.89 billion in 2012.[255] The country's capital city, Buenos Aires, is the most visited city in South America.[256] There are 30 National Parks of Argentina including many World Heritage Sites.

Transport

By 2004[update] Buenos Aires, all provincial capitals except Ushuaia, and all medium-sized towns were interconnected by 69,412 km (43,131 mi) of paved roads, out of a total road network of 231,374 km (143,769 mi).[257] In 2021, the country had about 2,800 km (1,740 mi) of duplicated highways, most leaving the capital Buenos Aires, linking it with cities such as Rosario and Córdoba, Santa Fe, Mar del Plata and Paso de los Libres (in border with Brazil), there are also duplicated highways leaving from Mendoza towards the capital, and between Córdoba and Santa Fé, among other locations.[258] Nevertheless, this road infrastructure is still inadequate and cannot handle the sharply growing demand caused by deterioration of the railway system.[259]

Argentina has the largest railway system in Latin America, with 36,966 km (22,970 mi) of operating lines in 2008[update], out of a full network of almost 48,000 km (29,826 mi).[260] This system links all 23 provinces plus Buenos Aires City, and connects with all neighbouring countries.[259] There are four incompatible gauges in use; this forces virtually all interregional freight traffic to pass through Buenos Aires.[259] The system has been in decline since the 1940s: regularly running up large budgetary deficits, by 1991 it was transporting 1,400 times less goods than it did in 1973.[259] However, in recent years the system has experienced a greater degree of investment from the state, in both commuter rail lines and long-distance lines, renewing rolling stock and infrastructure.[261][262] In April 2015, by overwhelming majority the Argentine Senate passed a law which re-created Ferrocarriles Argentinos (2015), effectively re-nationalising the country's railways, a move which saw support from all major political parties on both sides of the political spectrum.[263][264][265]

In 2012[update] there were about 11,000 km (6,835 mi) of waterways,[266] mostly comprising the La Plata, Paraná, Paraguay and Uruguay rivers, with Buenos Aires, Zárate, Campana, Rosario, San Lorenzo, Santa Fe, Barranqueras and San Nicolas de los Arroyos as the main fluvial ports. Some of the largest sea ports are La Plata–Ensenada, Bahía Blanca, Mar del Plata, Quequén–Necochea, Comodoro Rivadavia, Puerto Deseado, Puerto Madryn, Ushuaia and San Antonio Oeste. Buenos Aires has historically been the most important port; however since the 1990s the Up-River port region has become dominant: stretching along 67 km (42 mi) of the Paraná river shore in Santa Fe province, it includes 17 ports and in 2013[update] accounted for 50% of all exports.

In 2013[update] there were 161 airports with paved runways[267] out of more than a thousand.[259] The Ezeiza International Airport, about 35 km (22 mi) from downtown Buenos Aires,[268] is the largest in the country, followed by Cataratas del Iguazú in Misiones, and El Plumerillo in Mendoza.[259] Aeroparque, in the city of Buenos Aires, is the most important domestic airport.[269]

Energy

In 2020, more than 60% of Argentina's electricity came from non-renewable sources such as natural gas, oil and coal. 27% came from hydropower, 7.3% from wind and solar energy and 4.4% from nuclear energy.[271] At the end of 2021 Argentina was the 21st country in the world in terms of installed hydroelectric power (11.3 GW), the 26th country in the world in terms of installed wind energy (3.2 GW) and the 43rd country in the world in terms of installed solar energy (1.0 GW).[272]

The wind potential of the Patagonia region is considered gigantic, with estimates that the area could provide enough electricity to sustain the consumption of a country like Brazil alone. However, Argentina has infrastructural deficiencies to carry out the transmission of electricity from uninhabited areas with a lot of wind to the great centers of the country.[273]

In 1974 it was the first country in Latin America to put in-line a commercial nuclear power plant, Atucha I. Although the Argentine-built parts for that station amounted to 10% of the total, the nuclear fuel it uses are since entirely built in the country. Later nuclear power stations employed a higher percentage of Argentine-built components; Embalse, finished in 1983, a 30% and the 2011 Atucha II reactor a 40%.[274]

Science and technology

Argentines have received three Nobel Prizes in the Sciences. Bernardo Houssay, the first Latin American recipient, discovered the role of pituitary hormones in regulating glucose in animals, and shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1947. Luis Leloir discovered how organisms store energy converting glucose into glycogen and the compounds which are fundamental in metabolizing carbohydrates, receiving the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1970. César Milstein did extensive research in antibodies, sharing the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1984. Argentine research has led to treatments for heart diseases and several forms of cancer. Domingo Liotta designed and developed the first artificial heart that was successfully implanted in a human being in 1969. René Favaloro developed the techniques and performed the world's first coronary bypass surgery.

Argentina's nuclear programme has been highly successful. In 1957 Argentina was the first country in Latin America to design and build a research reactor with homegrown technology, the RA-1 Enrico Fermi. This reliance on the development of its own nuclear-related technologies, instead of buying them abroad, was a constant of Argentina's nuclear programme conducted by the civilian National Atomic Energy Commission (CNEA). Nuclear facilities with Argentine technology have been built in Peru, Algeria, Australia and Egypt. In 1983, the country admitted having the capability of producing weapon-grade uranium, a major step needed to assemble nuclear weapons; since then, however, Argentina has pledged to use nuclear power only for peaceful purposes.[275] As a member of the Board of Governors of the International Atomic Energy Agency, Argentina has been a strong voice in support of nuclear non-proliferation efforts[276] and is highly committed to global nuclear security.[277]

Despite its modest budget and numerous setbacks, academics and the sciences in Argentina have enjoyed international respect since the turn of the 1900s, when Luis Agote devised the first safe and effective means of blood transfusion as well as René Favaloro, who was a pioneer in the improvement of the coronary artery bypass surgery. Argentine scientists are still on the cutting edge in fields such as nanotechnology, physics, computer sciences, molecular biology, oncology, ecology and cardiology. Juan Maldacena, an Argentine-American scientist, is a leading figure in string theory.

Space research has also become increasingly active in Argentina. Argentine-built satellites include LUSAT-1 (1990), Víctor-1 (1996), PEHUENSAT-1 (2007),[278] and those developed by CONAE, the Argentine space agency, of the SAC series.[279] Argentina has its own satellite programme, nuclear power station designs (4th generation) and public nuclear energy company INVAP, which provides several countries with nuclear reactors.[280] Established in 1991, the CONAE has since launched two satellites successfully and,[281] in June 2009, secured an agreement with the European Space Agency for the installation of a 35-m diameter antenna and other mission support facilities at the Pierre Auger Observatory, the world's foremost cosmic ray observatory.[282] The facility will contribute to numerous ESA space probes, as well as CONAE's own, domestic research projects. Chosen from 20 potential sites and one of only three such ESA installations in the world, the new antenna will create a triangulation which will allow the ESA to ensure mission coverage around the clock[283] Argentina was ranked 76th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[284]

Demographics

The 2022 census [INDEC] conducted by the counted 46,044,703 inhabitants, up from 40,117,096 in 2010.[10][285][286] Argentina ranks third in South America in total population, fourth in Latin America and 33rd globally. Its population density of 15 persons per square kilometer of land area is well below the world average of 50 persons. The population growth rate in 2010 was an estimated 1.03% annually, with a birth rate of 17.7 live births per 1,000 inhabitants and a mortality rate of 7.4 deaths per 1,000 inhabitants. Since 2010, the crude net migration rate has ranged from below zero to up to four immigrants per 1,000 inhabitants per year.[287]

Argentina is in the midst of a demographic transition to an older and slower-growing population. The proportion of people under 15 is 25.6%, a little below the world average of 28%, and the proportion of people 65 and older is relatively high at 10.8%. In Latin America, this is second only to Uruguay and well above the world average, which is currently 7%. Argentina has a comparatively low infant mortality rate. Its birth rate of 2.3 children per woman is considerably below the high of 7.0 children born per woman in 1895,[288] though still nearly twice as high as in Spain or Italy, which are culturally and demographically similar.[289][290] The median age is 31.9 years and life expectancy at birth is 77.14 years.[291]

Attitudes towards LGBT people are generally positive within Argentina.[292] In 2010, Argentina became the first country in Latin America, the second in the Americas, and the tenth worldwide to legalize same-sex marriage.[293][294]

Ethnography

Argentina is considered a country of immigrants.[295][296][297] Argentines usually refer to the country as a crisol de razas (crucible of races, or melting pot). A 2010 study conducted on 218 individuals by the Argentine geneticist Daniel Corach established that the average genetic ancestry of Argentines is 79% European (mainly Italian and Spanish), 18% indigenous and 4.3% African; 63.6% of the tested group had at least one ancestor who was Indigenous.[298][299] The majority of Argentines descend from multiple European ethnic groups, primarily of Italian and Spanish descent, with over 25 million Argentines (almost 60% of the population) having some partial Italian origins.[300]

Argentina is also home to a notable Asian population, the majority of whom are descended from either West Asians (namely Lebanese and Syrians)[301] or East Asians (such as the Chinese,[302] Koreans, and the Japanese).[303] The latter of whom number around 180,000 individuals. The total number of Arab Argentines (most of whom are of Lebanese or Syrian origin) is estimated to be 1.3 to 3.5 million. Many immigrated from various Asian countries to Argentina during the 19th century (especially during the latter half of the century) and the first half of the 20th century.[304][305] Most Arab Argentines belong to the Catholic Church (including both the Latin Church and the Eastern Catholic Churches) or the Eastern Orthodox Church. A minority are Muslims. There are 180,000 Alawites in Argentina. [306][307]

From the 1970s, immigration has mostly been coming from Bolivia, Paraguay and Peru, with smaller numbers from the Dominican Republic, Ecuador and Romania.[308] The Argentine government estimates that 750,000 inhabitants lack official documents and has launched a program[309] to encourage illegal immigrants to declare their status in return for two-year residence visas—so far over 670,000 applications have been processed under the program.[310] As of July 2023, more than 18,500 Russians have come to Argentina after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[311]

Languages

The de facto[N] official language is Spanish, spoken by almost all Argentines.[312] The country is the largest Spanish-speaking society that universally employs voseo, the use of the pronoun vos instead of tú ("you"), which imposes the use of alternative verb forms as well. Owing to the extensive Argentine geography, Spanish has a strong variation among regions, although the prevalent dialect is Rioplatense, primarily spoken in the Pampean and Patagonian regions and accented similarly to the Neapolitan language.[313] Italian and other European immigrants influenced Lunfardo—the regional slang—permeating the vernacular vocabulary of other Latin American countries as well.

There are several second-languages in widespread use among the Argentine population: English (by 2.8 million people);[314] Italian (by 1.5 million people);[312][O] Arabic (specially its Northern Levantine dialect, by one million people);[312] Standard German (by 200,000 people);[312][P] Guaraní (by 200,000 people,[312] mostly in Corrientes and Misiones);[3] Catalan (by 174,000 people);[312] Quechua (by 65,000 people, mostly in the Northwest);[312] Wichí (by 53,700 people, mainly in Chaco[312] where, along with Kom and Moqoit, it is official de jure);[5] Vlax Romani (by 52,000 people);[312] Albanian (by 40,000 people);[315] Japanese (by 32,000 people);[312] Aymara (by 30,000 people, mostly in the Northwest);[312] and Ukrainian (by 27,000 people).[312]

Religion

Christianity is the largest religion in Argentina. The Constitution guarantees freedom of religion.[316] Although it enforces neither an official nor a state faith,[317] it gives Roman Catholicism a preferential status.[318][Q]

According to a 2008 CONICET poll, Argentines were 76.5% Catholic, 11.3% Agnostics and Atheists, 9% Evangelical Protestants, 1.2% Jehovah's Witnesses, and 0.9% Mormons, while 1.2% followed other religions, including Islam, Judaism and Buddhism.[320] These figures appear to have changed quite significantly in recent years: data recorded in 2017 indicated that Catholics made up 66% of the population, indicating a drop of 10.5% in nine years, and the nonreligious in the country standing at 21% of the population, indicating an almost doubling over the same period.[321]

The country is home to both one of the largest Muslim[319] and largest Jewish communities in Latin America, the latter being the seventh most populous in the world.[322] Argentina is a member of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance.[319]

Argentines show high individualization and de-institutionalization of religious beliefs;[323] 23.8% claim to always attend religious services; 49.1% seldom do and 26.8% never do.[324]

On 13 March 2013, Argentine Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the Cardinal Archbishop of Buenos Aires, was elected Bishop of Rome and Supreme Pontiff of the Catholic Church. He took the name "Francis", and he became the first Pope from either the Americas or from the Southern Hemisphere; he is the first Pope born outside of Europe since the election of Pope Gregory III (who was Syrian) in 741.[325]

Health

Health care is provided through a combination of employer and labour union-sponsored plans (Obras Sociales), government insurance plans, public hospitals and clinics and through private health insurance plans. Health care cooperatives number over 300 (of which 200 are related to labour unions) and provide health care for half the population; the national INSSJP (popularly known as PAMI) covers nearly all of the five million senior citizens.[326]

There are more than 153,000 hospital beds, 121,000 physicians and 37,000 dentists (ratios comparable to developed nations).[327][328] The relatively high access to medical care has historically resulted in mortality patterns and trends similar to developed nations': from 1953 to 2005, deaths from cardiovascular disease increased from 20% to 23% of the total, those from tumors from 14% to 20%, respiratory problems from 7% to 14%, digestive maladies (non-infectious) from 7% to 11%, strokes a steady 7%, injuries, 6%, and infectious diseases, 4%. Causes related to senility led to many of the rest. Infant deaths have fallen from 19% of all deaths in 1953 to 3% in 2005.[327][329]

The availability of health care has also reduced infant mortality from 70 per 1000 live births in 1948[330] to 12.1 in 2009[327] and raised life expectancy at birth from 60 years to 76.[330] Though these figures compare favorably with global averages, they fall short of levels in developed nations and in 2006, Argentina ranked fourth in Latin America.[328]

Education

The Argentine education system consists of four levels.[331] An initial level for children between 45 days to 5 years old, with the last two years[332] being compulsory. An elementary or lower school mandatory level lasting 6 or 7 years.[R] In 2010[update] the literacy rate was 98.07%.[333] A secondary or high school mandatory level lasting 5 or 6 years.[R] In 2010[update] 38.5% of people over age 20 had completed secondary school.[334] A higher level, divided in tertiary, university and post-graduate sub-levels. in 2013[update] there were 47 national public universities across the country, as well as 46 private ones.[335]

In 2010[update] 7.1% of people over age 20 had graduated from university.[334] The public universities of Buenos Aires, Córdoba, La Plata, Rosario, and the National Technological University are some of the most important. The Argentine state guarantees universal, secular and free-of-charge public education for all levels.[S] Responsibility for educational supervision is organized at the federal and individual provincial states. In the last decades the role of the private sector has grown across all educational stages.

Urbanization

Argentina is highly urbanized, with 92% of its population living in cities:[336] the ten largest metropolitan areas account for half of the population. About 3 million people live in the city of Buenos Aires, and including the Greater Buenos Aires metropolitan area it totals around 13 million, making it one of the largest urban areas in the world.[337] The metropolitan areas of Córdoba and Rosario have around 1.3 million inhabitants each.[337] Mendoza, San Miguel de Tucumán, La Plata, Mar del Plata, Salta and Santa Fe have at least half a million people each.[337]

The population is unequally distributed: about 60% live in the Pampas region (21% of the total area), including 15 million people in Buenos Aires province. The provinces of Córdoba and Santa Fe, and the city of Buenos Aires have 3 million each. Seven other provinces have over one million people each: Mendoza, Tucumán, Entre Ríos, Salta, Chaco, Corrientes and Misiones. With 64.3 inhabitants per square kilometre (167/sq mi), Tucumán is the only Argentine province more densely populated than the world average; by contrast, the southern province of Santa Cruz has around 1.1/km2 (2.8/sq mi).[338]

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Buenos Aires  Córdoba |

1 | Buenos Aires | (Autonomous city) | 3,003,000 | 11 | Resistencia | Chaco | 418,000 |  Rosario  Mendoza |

| 2 | Córdoba | Córdoba | 1,577,000 | 12 | Santiago del Estero | Santiago del Estero | 407,000 | ||

| 3 | Rosario | Santa Fe | 1,333,000 | 13 | Corrientes | Corrientes | 384,000 | ||

| 4 | Mendoza | Mendoza | 1,036,000 | 14 | Posadas | Misiones | 378,000 | ||

| 5 | San Miguel de Tucumán | Tucumán | 909,000 | 15 | San Salvador de Jujuy | Jujuy | 351,000 | ||

| 6 | La Plata | Buenos Aires | 909,000 | 16 | Bahía Blanca | Buenos Aires | 317,000 | ||

| 7 | Mar del Plata | Buenos Aires | 651,000 | 17 | Neuquén | Neuquén | 313,000 | ||

| 8 | Salta | Salta | 647,000 | 18 | Paraná | Entre Ríos | 283,000 | ||

| 9 | San Juan | San Juan | 542,000 | 19 | Formosa | Formosa | 256,000 | ||

| 10 | Santa Fe | Santa Fe | 540,000 | 20 | Comodoro Rivadavia | Chubut | 243,000 | ||

Culture

Argentina is a multicultural country with significant European influences. Modern Argentine culture has been largely influenced by Italian, Spanish and other European immigration from France, Russia, United Kingdom, among others. Its cities are largely characterized by both the prevalence of people of European descent, and of conscious imitation of American and European styles in fashion, architecture and design.[340] Museums, cinemas, and galleries are abundant in all the large urban centres, as well as traditional establishments such as literary bars, or bars offering live music of a variety of genres although there are lesser elements of Amerindian and African influences, particularly in the fields of music and art.[341] The other big influence is the gauchos and their traditional country lifestyle of self-reliance.[342] Finally, indigenous American traditions have been absorbed into the general cultural milieu. Argentine writer Ernesto Sabato has reflected on the nature of the culture of Argentina as follows:

With the primitive Hispanic American reality fractured in La Plata Basin due to immigration, its inhabitants have come to be somewhat dual with all the dangers but also with all the advantages of that condition: because of our European roots, we deeply link the nation with the enduring values of the Old World; because of our condition of Americans we link ourselves to the rest of the continent, through the folklore of the interior and the old Castilian that unifies us, feeling somehow the vocation of the Patria Grande San Martín and Bolívar once imagined.

— Ernesto Sabato, La cultura en la encrucijada nacional (1976)[343]

Literature

Although Argentina's rich literary history began around 1550,[344] it reached full independence with Esteban Echeverría's El Matadero, a romantic landmark that played a significant role in the development of 19th century's Argentine narrative,[345] split by the ideological divide between the popular, federalist epic of José Hernández' Martín Fierro and the elitist and cultured discourse of Sarmiento's masterpiece, Facundo.[346]

The Modernist movement advanced into the 20th century including exponents such as Leopoldo Lugones and poet Alfonsina Storni;[347] it was followed by Vanguardism, with Ricardo Güiraldes's Don Segundo Sombra as an important reference.[348]

Jorge Luis Borges, Argentina's most acclaimed writer and one of the foremost figures in the history of literature,[349] found new ways of looking at the modern world in metaphor and philosophical debate and his influence has extended to authors all over the globe. Short stories such as Ficciones and The Aleph are among his most famous works. He was a friend and collaborator of Adolfo Bioy Casares, who wrote one of the most praised science fiction novels, The Invention of Morel.[350] Julio Cortázar, one of the leading members of the Latin American Boom and a major name in 20th century literature,[351] influenced an entire generation of writers in the Americas and Europe.[352]

A remarkable episode in Argentine literary history is the social and literarial dialectica between the so-called Florida Group, named this way because its members used to meet together at the Richmond Cafeteria at Florida street and published in the Martin Fierro magazine, such as Jorge Luis Borges, Leopoldo Marechal, Antonio Berni (artist), among others; versus the Boedo Group of Roberto Arlt, Cesar Tiempo, Homero Manzi (tango composer), that used to meet at the Japanese Cafe and published their works with the Editorial Claridad, with both the cafe and the publisher located at Boedo Avenue.

Other highly regarded Argentine writers, poets and essayists include Estanislao del Campo, Eugenio Cambaceres, Pedro Bonifacio Palacios, Hugo Wast, Benito Lynch, Enrique Banchs, Oliverio Girondo, Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, Victoria Ocampo, Leopoldo Marechal, Silvina Ocampo, Roberto Arlt, Eduardo Mallea, Manuel Mujica Láinez, Ernesto Sábato, Silvina Bullrich, Rodolfo Walsh, María Elena Walsh, Tomás Eloy Martínez, Manuel Puig, Alejandra Pizarnik, and Osvaldo Soriano.[353]

Music