Henry Baldwin (judge)

Henry Baldwin | |

|---|---|

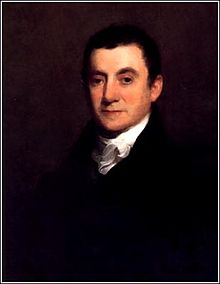

Portrait by Thomas Sully, 1834 | |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office January 18, 1830 – April 21, 1844 | |

| Nominated by | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | Bushrod Washington |

| Succeeded by | Robert Cooper Grier |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 14th district | |

| In office March 4, 1817 – May 8, 1822 | |

| Preceded by | John Woods |

| Succeeded by | Walter Forward |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 14, 1780 New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | April 21, 1844 (aged 64) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Greendale Cemetery Meadville, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (Before 1825) Democratic (1828–1844) |

| Education | Yale College (BA) Litchfield Law School |

Henry Baldwin (January 14, 1780 – April 21, 1844) was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from January 6, 1830, to April 21, 1844.

Early life and education

[edit]Baldwin descended from an aristocratic British family dating back to the 17th century. He was born in New Haven, Connecticut, the son of Michael Baldwin and Theodora Walcott. He was the half-brother of Abraham Baldwin. He attended Hopkins School, and received a B.A. at age 17 from Yale College in 1797, where he was also a member of Brothers in Unity. He also attended Litchfield Law School and read law in 1798. Baldwin then moved to Pittsburgh and established a successful law practice. He invested in iron furnaces north of the city, which prompted a move to Crawford County, Pennsylvania, of which he was elected the newly formed jurisdiction's first district attorney and served from 1799 to 1801. He was also the publisher of The Tree of Liberty, a Democratic-Republican newspaper.

After the death of his first wife, Marana Norton, Baldwin married Sally Ellicott. He was elected to the United States Congress as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party in 1816, representing Pennsylvania's 14th congressional district; he was reelected twice, but resigned in May 1822 due to poor health. Before resigning from Congress in 1822, he planted the seeds of a future political alliance with General Jackson by advising that Congress drop an investigation of unsanctioned military aggression in Florida. In 1828, Jackson rewarded his political services in Pennsylvania and advisory role in the presidential campaigns of 1824 and 1828 by nominating him to the cabinet post of Secretary of the Treasury. Jackson's first attempt at nomination was blocked in the Senate by then Vice President John Calhoun, largely because of Baldwin's strong position in favor of high-tariff policy. Baldwin served in this role until late 1829.[1] His political popularity can be traced to his private investment in the economic growth of Pittsburgh. In the House, he was a prominent advocate of protective tariffs. He received support from Independent Republicans and Federalists for his support of the protective tariff as a national measure. He strongly supported the election of Andrew Jackson in the election of 1824 and 1828. When Bushrod Washington died after thirty-two years of service on the Supreme Court, the president appointed Baldwin to replace him. On January 6, 1830, the Senate approved Baldwin's nomination to the Supreme Court 41 to 2 despite the Calhoun's efforts. The only dissenters were the two senators from Calhoun's home state of South Carolina.[1] On January 18, 1830, Baldwin took the judicial oath to become an associate justice.

Baldwin considered resigning from the court in 1831. In a letter to President Jackson, he complained about the Court's extension of its powers. Some historians believe that Baldwin suffered from mental illness during this period. However, he continued to serve on the court until his death in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1838, Baldwin was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[2]

Views

[edit]Baldwin was personally involved in cases on the issue of slavery. In the case of Johnson v. Tompkins, 13 F. Cas. 840 (C.C.E.D. Pa. 1833), he instructed the jury that although slavery's existence "is abhorrent to all our ideas of natural right and justice," the jury must respect the legal status of slavery. He was the sole dissenter in the case United States v. The Amistad, in which Associate Justice Joseph Story delivered the Court's decision to free the 36 kidnapped African adults and children who were on board the schooner, La Amistad. In Groves v. Slaughter, 40 U.S. (15 Pet.) 449 (1841), Justice Baldwin emphatically expressed his opinion that, as a matter of constitutional law, slaves are property, not persons.

In another federal case, Baldwin interpreted the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Constitution. That case was Magill v. Brown, 16 Fed. Cas. 408 (C.C.E.D. Pa. 1833), in which Baldwin stated: "We must take it therefore as a grant by the people of the state in convention, to the citizens of all the other states of the Union, of the privileges and immunities of the citizens of this state." This eventually became the view accepted by the Supreme Court, and remains so. He also interpreted the Clause that way, in dictum, when speaking for the Court in Rhode Island v. Massachusetts, 37 U.S. (12 Pet.) 657, 751 (1838) (each State "by the Constitution has agreed that those of any other state shall enjoy rights, privileges, and immunities in each, as its own do").

Even though Baldwin's opinions on the Court and his treatise were politically, jurisprudentially contrary to Marshall's overarching influence on the Court, he was a friend and admirer of Chief John Marshall. He wrote of Marshall that "no commentator ever followed the text more faithfully, or ever made a commentary more accordant with its strict intention and language." Baldwin was at Marshall's bedside when the old Chief Justice died in 1835.

In 1837, Baldwin authored a treatise titled A General View of the Origin and Nature of the Constitution and Government of the United States: Deduced from the Political History and Condition of the Colonies and States.[3] Baldwin opposed the two prevailing schools of Constitutional interpretation: the strict constructionists and the school of liberal interpretation. Likewise, his views followed a middle course between the extremes of states' rights on the one hand, and nationalism on the other hand.

Critical cases

[edit]Worcester v. Georgia (1832)

[edit]A case that demonstrates Baldwin's admittedly inconsistent record of writing opinions and political boldness, as well as his unique style of jurisprudence is Worcester v. Georgia (1831). The statute in question was one of the "Indian laws" passed by the state legislature of Georgia forbidding white men from residing in Cherokee territory without a license from the state. Samuel Worcester and Elizur Butler, two missionaries who had been living with the Cherokees, were arrested in March 1831 for violating that statute. The Superior Court of Gwinnett County, Georgia, a trial court, which claimed that they were federal employees exempt from the law, subsequently released Worcester and Butler.[4] Worcester and Butler were arrested again, convicted of violating the statute, and sentenced to four years in prison. They were offered a pardon, but refused, and appealed their case to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court received this case because the clerk of the county court responded to this Writ of Error, although the judge never signed it. The state of Georgia never appeared in court, and publicly announced that it would disregard any decree of the court overturning the conviction.

The case was decided with five concurring in the majority (including Marshall), McLean in concurrence, and Baldwin in dissent. Johnson was absent because of ill health. Story and Thompson's support for the Cherokees was on record, and Marshall's sympathetic posture paralleled his prior Cherokee Nation opinion. The court issued its decision on March 3, 1832, that the Georgia statutes were unconstitutional as applied to the Cherokee tribes. Marshall wrote for Duvall, Story, and Thompson. Baldwin based his dissent on his conclusion that the court lacked jurisdiction, as the record had been returned by the Georgia court clerk, and not by the court itself. He agreed with Justice Marshall's opinion exclusively on his holding that the Cherokees were a sovereign nation "which this court is bound to judicially know as such to have and possess a jurisdiction over the lands they occupy." Continuing his dissent, Baldwin ruled that the "national existence of the Indian tribes," according to the Constitution, was subject to the power of Georgia "by her own right and the Compact of 1802."[5] Yet Baldwin never delivered his opinion to Reporter Peters.[6] On March 3, 1832, many newspapers undertook the publishing of the opinions of the Court. As part of its anti-Worcester campaign, the principal press organ of the Jackson administration published Johnson's anti-Cherokee concurrence in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and promised to follow with Baldwin's Worcester dissent. Marshall's Worcester opinion appeared on March 22. Baldwin's lone dissent, delivered by a Jackson appointee, in a significant challenge by the collective Court to the Jackson administration had not yet appeared in print. Referring to the Court Report and an article published by the Washington Globe on March 3, 1832, one scholar concludes that the non-disclosure of his dissent is indicative of Baldwin's awareness of the tense political climate over states' rights at the time.[7] Another case in which Baldwin dissented was United States v. Amistad (1841), but as was common throughout Baldwin's career, the opinion was not released.

Groves v. Slaughter (1841)

[edit]Baldwin issued a concurring opinion concerning the police power and interstate commerce in Groves v. Slaughter (1841). The facts of the case include that John W. Brown, in Mississippi, purchased slaves from Slaughter of Louisiana. Groves and Graham had signed as guarantors a note of purchase for seven thousand dollars for the benefit of Brown, but when the note was due Brown refused to pay it.[8] Groves contended that the Mississippi Constitution of 1832, which prohibited the importation of slaves merchandise after May 1, 1833, voided the note. Slaughter brought the suit to federal court, and the differing citizenships as well as the amount of legal tender involved met the requirement necessary for an appeal to the United States Supreme Court. When Groves lost his case in the federal circuit, he appealed to the Supreme Court.[9] Justice Smith Thompson held the majority of the court, and concluded that a statute was necessary before Mississippi's constitutional provision would take effect, affirming the lower court ruling. Thompson avoided the question of whether the Mississippi Constitution violated the United States Constitution by infringing on the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce.[10] After McLean and Taney gave their opinions on the subject, Baldwin came forth with his own opinion "lest it be inferred" that his opinions coincided with that of the other justices.[8]

In a concurring opinion, Baldwin opposed Taney and McLean's concurrences on questions about the commerce clause that were not needed to resolve the case. Chief Justice Taney had written separately to state that the importation of slaves "cannot be controlled by Congress".[8] Baldwin argues for five pages his position that slaves are property "wherever slavery exists". Mary Sarah Bilder says Baldwin's purpose in making these arguments was "oblique".[11]

Paul Finkelman says that by seeking to protect "the rights of masters who might travel to free states" Baldwin's argument that slaves are property (not people) under the federal constitution was more "shrewd and realistic" than Taney's argument rejecting Congressional authority.[8][12]

Responding to Justice McLean's pro-abolition defense that laws abolishing slavery were "local in character" and within the rights of state sovereignty Baldwin agreed that any state could abolish slavery but transit of property including slaves, "is lawful commerce among the several states, which none can prohibit or regulate, which the constitution protects, and Congress may, and ought to preserve from violation."[8]

Finkelman compares McLean's abolitionist stand with Baldwin's arguments rejecting the proposition that slaves were "persons" under the Constitution:[8]

McLean looked to the Constitution to prove that slaves were "persons," Baldwin looked to "the law of the states before the adoption of the Constitution, and from the first settlement of the colonies" to show that they were property. He also found support for this principle "in our diplomatic relations...and in the most solemn international acts, from 1782 to 1815." That he might "stand alone" on the court did "not deter" him from declaring that slaves should be considered property and thus be protected while in transit.

Baldwin argues that a state can not restrict importation of slaves for sale if slavery was otherwise permitted.[8][13] The state constitution could restrict importation of slaves under its police power for welfare and safety reasons but it could not restrict importation of slaves for sale when slavery was permitted in general.[14] He concludes that the right to collect on the defaulted note would be protected under the Federal Constitution even if it was not protected by the state constitution of Mississippi.[15]

A General View of the Origin and Nature of the Constitution and Government of the United States (1837)

[edit]Baldwin was aware that his style of jurisprudence was inconsistent, often extreme, and politically inconsistent with his appointment. He acknowledged this in his 1837 work on the origin and nature of the United States Constitution and Government that "I am well aware of departing from the modern mode of construing our ancient charters."[16] Strikingly, the eccentric Baldwin nearly mirrors the structure-oriented, original-intent approach of Justice Antonin G. Scalia[dubious – discuss]. Baldwin speaks on issues such as territory rights, the Articles of Confederation, State Sovereignty, Contract Cases, Definitions of A Corporation, etc. He holistically delineates his view on Constitutional issues beginning with the Founding of the nation. Further, despite his expressed affection for Marshall, Baldwin's work counters Marshall's expansive use of the Constitution to expand the prestige of the Court. Referring to McCulloch v. Maryland, Baldwin explains that "he has given no construction to the constitution; he has only declared what it says, by carrying out the general terms it uses, and making a practical application thereof, to the various cases, in which he has delivered the opinion of the Court."[17] Baldwin's work is based on the Constitution and the Federal Government as instruments of the people, his interpretation of the original intent of the Founders, the influence of English Common Law as a "standard rule by which to measure the different parts of the Supreme Law," and, lastly, the federal government holding a 'grant' of power that can be defined explicitly by the supreme law of the Constitution.[18] Justice Story saw this work as imposing "severe strictures" on his work, Commentaries on the Constitution, and on the Constitution itself.[19]

Death and legacy

[edit]Baldwin's time on the court was punctuated by physical and mental health problems as well as a tendency to shed the legal, social, and political norms of the court. One scholar, G. Edward White, has suggested that Baldwin's lack of "any historical reputation" results not from any lack of intrinsic interestingness but from his "incoherence as a jurist."[20] Though White is particularly unforgiving, this is the general consensus of modern scholarship for Baldwin's 15-year term on the court. The most complimentary of scholarly opinion on Baldwin praises his role as an "unyielding champion of the Constitution and the federal system," but at the same time labels him a "political maverick."[21]

Baldwin suffered from paralysis in later years and died a pauper, aged 64. Historian William J. Novak of the University of Chicago has written that "Baldwin's jurisprudence has been treated rather shabbily by historians."[22]

Baldwin's remains were initially interred at Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C. His remains were later disinterred and moved to Greendale Cemetery, Meadville, Pennsylvania.[23] He is the namesake of Baldwin, Pennsylvania.[24]

He was the half-brother of United States Constitution signatory Abraham Baldwin.

His home is now a museum and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

See also

[edit]Published works

[edit]- Baldwin, Henry (1837). A General View Of The Origin And Nature Of The Constitution And Government Of The United States, Deduced From The Political History And Condition Of The Colonies And States, From 1774 Until 1788. Read Books Design. ISBN 1-4460-6139-6.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Abraham, Henry Julian (1985). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0-19-503479-1.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Baldwin, Henry (1837). A General View of the Origin and Nature of the Constitution and Government of the United States: Deduced from the Political History and Condition of the Colonies and States, from 1774 Until 1788. J. C. Clark. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ Swisher, Carl Brent (1974). The Marshall Court and Cultural Change, 1815–35. New York: Macmillan. p. 731. ISBN 0-02-541360-0.

- ^ Dissenting opinion provided by Robertson, Lyndsay G. (1999). "Justice Henry Baldwin's 'Lost Opinion' in Worcester v. Georgia". Journal of Supreme Court History. 24 (1): 50–75. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5818.1999.tb00149.x. S2CID 145491176.

- ^ Swisher, Carl Brent (1974). The Marshall Court and Cultural Change, 1815–35. New York: Macmillan. p. 733. ISBN 0-02-541360-0.

- ^ Washington Globe March 3, 1832, in Robertson, Lyndsay G. (1999). "Justice Henry Baldwin's 'Lost Opinion' in Worcester v. Georgia". Journal of Supreme Court History. 24 (1): 50–75. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5818.1999.tb00149.x. S2CID 145491176.

- ^ a b c d e f g Finkelman, Paul (1981). An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 266–271. ISBN 0-8078-4066-1.

- ^ Groves et al. v. Slaughter, 40 US (15 Pet.) 449 (1841), 497. (1841).

- ^ Groves et al. v. Slaughter, 40 US (15 Pet.) 449 (1841) 510 (1841).

- ^ Bilder, Mary Sarah (1996). "The Struggle Over Immigration: Indentured Servants, Slaves and Articles of Commerce". Missouri Law Review. 61 (4): 811.

- ^ See also Dred Scott decision

- ^ Currie, David P. (1983). "The Constitution in the Supreme Court: Contracts and Commerce, 1836-1864". Duke Law Journal. 1983 (3): 498.

- ^ Eastman, John C.; Jaffa, Harry V. (1996). "REVIEW Understanding Justice Sutherland As He Understood Himself". The University of Chicago Law Review. 63 (3): 1369.

- ^ 40 US 517

- ^ Henry Baldwin, A General View of the Origin and Nature of the Constitution and Government of the United States Deduced from the Political History and Condition of the Colonies and States from 1774 Until 1788, and the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States, Together with Opinions in the Cases Decided at January Term, 1837, Arising on the Restraints on the Powers of the States (Philadelphia: J.C. Clark, 1837), xvii.

- ^ Henry Baldwin, A General View of the Origin and Nature of the Constitution and Government of the United States, 89.

- ^ Henry Baldwin, A General View of the Origin and Nature of the Constitution and Government of the United States, 11.

- ^ William Wetmore Story, Life and Letters of Joseph Story Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, and Dane Professor of Law at Harvard University (Boston: C.C. Little and J. Brown 1851), 273.

- ^ G. Edward White and Gerald Gunther, The Marshall Court and Cultural Change, 1815–35 (New York: Macmillan: 1988), 301.

- ^ Robert D. Ilisevich, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies,1789–1995 (Clare Cushman, ed., 1995), 110.

- ^ Novak, William J. (1996). The People's Welfare: Law and Regulation in Nineteenth-century America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4611-2. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ "Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook". Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. Retrieved November 24, 2013. Supreme Court Historical Society at Internet Archive.

- ^ Ackerman, Jan (May 10, 1984). "Town names carry bit of history". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Huebner, Timothy S.; Renstrom, Peter; Hall, Kermit L., coeditor. (2003) The Taney Court, Justice Rulings and Legacy. City: ABC-Clio Inc.ISBN 1576073688.

- Lewis, Walker (1965). Without Fear or Favor: A Biography of Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Seddig, Robert G. (1992). Hall, Kermit L. (ed.). "Henry Baldwin", The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- White, G. Edward. The Marshall Court & Cultural Change, 1815–35. Published in an abridged edition, 1991.

External links

[edit]- Henry Baldwin at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- United States Congress. "Henry Baldwin (id: B000087)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- The Political Graveyard

- Legal Encyclopedia

- Ariens, Michael, Henry Baldwin biography

- Baldwin Reynolds House Museum, Crawford County Historical Society

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Baldwin, Henry". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. p. 196.

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Baldwin, Henry". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. p. 196.- Henry Baldwin at Find a Grave

- Fox, John, Capitalism and Conflict, Biographies of the Robes, Henry Baldwin. Public Broadcasting Service

- Oyez, Official Supreme Court media, Henry Baldwin

- 1780 births

- 1844 deaths

- 19th-century American judges

- 19th-century American legislators

- 19th-century American Episcopalians

- American people of English descent

- Burials at Greendale Cemetery

- Burials at Oak Hill Cemetery (Washington, D.C.)

- Democratic-Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania

- Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Lawyers from New Haven, Connecticut

- Pennsylvania Democrats

- Pennsylvania lawyers

- Pennsylvania state court judges

- Politicians from New Haven, Connecticut

- Politicians from Pittsburgh

- United States federal judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law

- United States federal judges appointed by Andrew Jackson

- Yale College alumni