Islam in Maldives

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Islam is the state religion of Maldives. The 2008 Constitution or "Fehi Gānoon" declares the significance of Islamic law in the country. The constitution requires that citizenship status be based on adherence to the state religion, which legally makes the country's citizens 100% Muslim.

History

[edit]

Islamic influence in the Maldives may date as far back as the 10th century, with mentions of the region by Arabic accounts dating to around the 9th and 10th centuries.[1] The importance of the Arabs as traders in the Indian Ocean by the 12th century may partly explain why the last Buddhist king of Maldives Dhovemi converted to Islam in the year 1153[2] (or 1193, for certain copper plate grants give a later date[citation needed]). The king thereupon adopted the Muslim title and name (in Arabic) of Sultan (besides the old Dhivehi title of Maha Radun or Ras Kilege or Rasgefānu[citation needed]) Muhammad al-Adil, initiating a series of six Islamic dynasties consisting of eighty-four sultans and sultanas that lasted until 1932 when the sultanate became elective.[2] The formal title of the Sultan up to 1965 was, Sultan of Land and Sea, Lord of the twelve-thousand islands and Sultan of the Maldives which came with the style Highness.[citation needed] The person traditionally deemed responsible for this conversion was a Sunni Muslim visitor named Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari.[2] His venerated tomb now stands on the grounds of Medhu Ziyaaraiy, opposite[citation needed] the Hukuru Mosque in the capital Malé.[2] Built in 1656, this is the oldest mosque in Maldives.[2]

Scholars believe that the Islamization of the Maldives was a gradual process that likely took centuries, beginning before the official conversion of king Dhovemi and ending significantly after his conversion.[1]

Introduction of Islam

[edit]Maghrebi/Berber theory Arab interest in the Maldives also was reflected in the residence there in the 1340s of Ibn Battutah.[2] The well-known Moroccan traveller wrote how a Berber from North Morocco, one Abu Barakat Yusuf the Berber, was believed to have been responsible for spreading Islam in the islands, reportedly convincing the local king after having subdued Ranna Maari, a monster coming from the sea.[3] Even though this report has been contested in later sources, it does explain some crucial aspects of Maldivian culture. For instance, historically Arabic has been the prime language of administration there, instead of the Persian and Urdu languages used in the nearby Muslim states. Another link to North Africa was the Maliki school of jurisprudence, used throughout most of North Africa, which was the official one in the Maldives until the 17th century.[4]

Somali theory

[edit]Some scholars have suggested the possibility of Ibn Battuta misreading Maldive texts, and having a bias or felt partial towards the North African Maghrebi/Berber narrative of this Shaykh. Instead of the East African origins account that was known as well at the time.[5] Even when Ibn Battuta visited an island of the Maldives, the governor of the island at that time was Abd Aziz Al Mogadishawi, a Somali.[6]

Also another prominent Shaykh on the island during Ibn Battuta's stay, was Shaykh Najib al Habashi Al Salih, another learned man from the Horn of Africa. His presence Indicating a strong Horn of African Islamic presence on the Island.[7]

Scholars have spoken that Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari might have been a resident of Berbera, a significant trading port on the north western coast of Somaliland.[8] Barbara or Barbaroi (Berbers), as the ancestors of the Somalis were referred to by medieval Arab and ancient Greek geographers, respectively.[9][10][11] This is also seen when Ibn Battuta visited Mogadishu, he mentions that the Sultan at that time 'Abu Bakr ibn Shaikh Omar', was a Berber (Somali).

Persian theory

[edit]Another interpretation, in the Raadavalhi and Taarikh,[12][13] is that Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari was Abu al-Barakat Yusuf Shams ud-Din at-Tabrizi, also locally known as Tabrīzugefānu. In the Arabic script the words al-Barbari and al-Tabrizi are very much alike, since, at the time, Arabic had several consonants that looked identical and could only be differentiated by overall context (this has since changed by addition of dots above or below letters to clarify pronunciation – For example, the letter "ب" in modern Arabic has a dot below, whereas the letter "ت" looks identical except there are two dots above it). "ٮوسڡ الٮٮرٮرى" could be read as "Yusuf at-Tabrizi" or "Yusuf al-Barbari".

Islamic influence

[edit]Islam is the state religion of Maldives, and adherence to it is legally required for citizens by a revision of the constitution in 2008: Article 9, Section D and 10 states,

A non-Muslim may not become a citizen of the Maldives.[14] The religion of the State of the Maldives is Islam. Islam shall be the one of the basis of all the laws of the Maldives. No law contrary to any tenet of Islam shall be enacted in the Maldives.[15]

The traditional Islamic law code of sharia forms the Maldives' basic code of law, as interpreted to conform to local Maldivian conditions by the President, the attorney general, the Ministry of Home Affairs, and the Majlis.[2] Article 142 of the constitution states,

When deciding matters on which the Constitution or the law is silent, Judges must consider Islamic Shari’ah.[15]

Proselytizing by non-Muslims in Maldives, including the public possession and distribution of non-Muslim religious materials (such as the Bible), is illegal. Public worship by adherents of religions other than Islam is forbidden.[16]

On the inhabited islands, the mosque forms the central place where Islam is practiced.[2] Because Friday is the most important day for Muslims to attend the mosque, shops and offices in towns and villages close around 11 a.m., and the sermon begins by 12:35 p.m.[2]

The prayer call is performed by the Mudhimu (Muezzin).[2] Most shops and offices close for fifteen minutes after each call.[2] During the ninth Muslim month of Ramadan, cafés and restaurants are closed during the day, and working hours are limited.[2]

Mosques

[edit]Most inhabited Maldivian islands have several mosques; Malé has more than thirty.[2] Most traditional mosques are whitewashed buildings constructed of coral stone with corrugated iron or thatched roofs.[2]

-

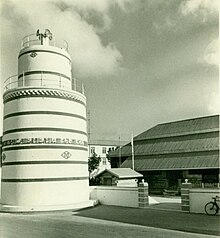

Dadimagi miskit in Fuvahmulah, 1981

-

Kede-ere miskit in Fuvahmulah, 1981

-

Gen Miskit, Fuvahmulah, 1984

-

Dharavandhoo Friday Mosque

-

Bandos island mosque, North Male Atholl

-

A mandala on the ceiling of Darumavanta Rasgefaanu mosque, Malé. Lacquered wood carving. The damaged Mandala was covered with a simple geometrical drawing painted on plywood.

-

Photograph of a mandala on the ceiling. Lacquered wood carving; quite damaged. Kalhuhuraage mosque, Malé, Maldives, 1987

-

Photograph of a mandala carving on wooden door panel. Fua Mulaku Island, 1986

-

Photograph of a mandala on the ceiling. Lacquered wood carving. 'Idu mosque, Malé, 1989

In Malé, the Islamic Centre and the Grand Friday Mosque, built in 1984 with funding from the Persian Gulf states, Pakistan, Brunei, and Malaysia, are imposing, elegant structures.[2] The gold-colored dome of this mosque is the first structure sighted when approaching Malé.[2] In mid-1991 Maldives had a total of 724 mosques and 266 women's mosques.[2]

-

Old Mosque of Malé, white coral decorations

-

Sample of decorative Arabic writing on lacquered wooden panel. Idu Miskit, Malé

-

Filitheyo graveyard

Radicalism

[edit]The Guardian estimates that 50-100 fighters have joined ISIS and al-Qaeda from the Maldives.[17] The Financial Times puts the number at 200.[18]

- 2007 Malé bombing: On 29 September 2007 a homemade bomb went off in Sultan Park near the Islamic Centre in the Maldivian capital Malé, injuring 12 foreign tourists. In December, three men were sentenced to 15 years in jail after they confessed to the bombing. Two of those imprisoned, Mohamed Sobah and Ahmed Amin - both Maldivian natives in their early twenties-had their sentences changed from incarceration to three-year suspended sentences under observation and were later set free in August 2010.[19]

- 2011 Ismail Khilath Rasheed controversy: In February 2012 almost all the Maldives National Museum's pre-Islamic artifacts, dating back to before the 12th century, were destroyed during an attack: "Some of the pieces can be put together but mostly they are made of sandstone, coral and limestone, and they are reduced to powder." He said the museum had "nothing [left] to show" of the country's pre-Islamic history.[20][21] Among the damaged objects were a six-faced coral statue, an 18 in (46 cm) high bust of Buddha, as well as assorted limestone and coral statues[22]

Religious Stand of Maldives and Public Etiquette

[edit]In 2008 after the ratification of the new constitution, multi-party democracy was instated in the Maldives.

The Maldivian religious party named the Adhaalath Party was founded by the religious scholars and religious activists. Under the new freedom of speech and relaxed laws radicalism and different forms of religious factions rose in Maldives.

The religious extremism was controlled by the state, since in every presidency the coalition governments consisted with the Adhaalath Party's affiliation. The Islamic Ministry and major executive portfolio is represented by the Adaalath Party. In the Maldives, general clothing guidelines are observed as per democratic law instated and extremism is punishable by lengthy jail sentences.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Wille, Boris (2022-11-22), "The Appropriation of Islam in the Maldives", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7, retrieved 2024-05-09

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Ryavec, Karl E. (1995). "Maldives: Religion". In Metz, Helen Chapin (ed.). Indian Ocean: five island countries (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 267–269. ISBN 0-8444-0857-3. OCLC 32508646.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1354, tr. and ed. H. A. R. Gibb (London: Broadway House, 1929)

- ^ The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveller of the Fourteenth Century

- ^ Honchell, Stephanie (2018), Sufis, Sea Monsters, and Miraculous Circumcisions: Comparative Conversion Narratives and Popular Memories of Islamization, Fairleigh Dickinson University and the University of Cape Town, p. 5,

In reference to Ibn Battuta's Moroccan theory of this figure, citation 8 of this text mentions, that other accounts identify Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari as East African or Persian. But as fellow Maghribi, Ibn Battuta likely felt partial to the Moroccan version.

- ^ Defremery, C. (December 1999). Ibn Battuta in the Maldives and Ceylon. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120612198.

- ^ Takahito, Mikasa no Miya (1988). Cultural and Economic Relations Between East and West: Sea Routes. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447026987.

- ^ "Richard Bulliet – History of the World to 1500 CE (Session 22) – Tropical Africa and Asia". Youtube.com. 23 November 2010. Archived from the original on 2021-12-22. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ F. R. C. Bagley et al., The Last Great Muslim Empires (Brill: 1997), p. 174.

- ^ Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p. 13.

- ^ James Hastings, Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Part 12: V. 12 (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2003), p. 490.

- ^ Kamala Visweswaran (6 May 2011). Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and Representation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-1-4051-0062-5.

- ^ Ishtiaq Ahmed (2002). Ingvar Svanberg; David Westerlund (eds.). Islam Outside the Arab World. Indiana University Press. p. 250. ISBN 9780253022608.

- ^ Ran Hirschl (2010). Constitutional Theocracy. Harvard University Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780674059375.

- ^ a b "The Constitution of Maldives". Attorney General's office, Republic of Maldives.

- ^ "The Protection of Religious Unity of the People Act (Dhivehi)". mvlaw.gov.mv. Law No. 6/94 Attorney General's Office, Republic of Maldives. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Jason Burke (February 26, 2015). "Paradise jihadis: Maldives sees surge in young Muslims leaving for Syria". Guardian.

- ^ Victor Mallet (December 4, 2015). "The Maldives: Islamic Republic, Tropical Autocracy". Financial Times.

- ^ Anupam Dasgupta (2011-01-23). "A Male-volent link". The Week. Archived from the original on 2011-01-24.

It surprised India when Nasheed freed two prime accused in the 2007 Sultan Park bombings in Male in August 2010. We are planning to send Mohamed Sobah and Ahmed Naseer [the two accused] back to jail. We feel they are dangerous to our society and we are not willing to risk internal security, said Ahmed Muneer, deputy commissioner of the Maldives police.

- ^ Trouble in paradise: Maldives and Islamic extremism

- ^ "Maldives museum reopens minus smashed Hindu images"[permanent dead link], Associated Press, 14 February 2012

- ^ Bajaj, Vikas (13 February 2012). "Vandalism at Maldives Museum Stirs Fears of Extremism". The New York Times.