The Devil's Advocate (1997 film)

| The Devil's Advocate | |

|---|---|

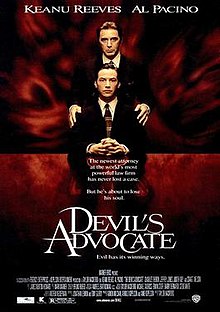

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Taylor Hackford |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | The Devil's Advocate by Andrew Neiderman |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Andrzej Bartkowiak |

| Edited by | Mark Warner |

| Music by | James Newton Howard |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 144 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $57 million[2] |

| Box office | $153 million[2] |

The Devil's Advocate (marketed as Devil's Advocate) is a 1997 American supernatural horror film directed by Taylor Hackford, written by Jonathan Lemkin and Tony Gilroy, and starring Keanu Reeves, Al Pacino and Charlize Theron. Based on Andrew Neiderman's 1990 novel, it is about a gifted young Florida lawyer invited to work for a major New York City law firm. As his wife becomes haunted by frightening visions, the lawyer slowly realizes that the firm's owner John Milton is the Devil.

The name John Milton is one of several allusions to Paradise Lost, as well as to Dante Alighieri's Inferno and the legend of Faust. An adaptation of Neiderman's novel went into a development hell during the 1990s, with Hackford gaining control of the production. Filming took place around New York City and Florida.

The Devil's Advocate received mixed reviews, with critics crediting it for entertainment value and Pacino's performance. It grossed $153 million at the box office and won the Saturn Award for Best Horror Film. It also became the subject of the copyright lawsuit Hart v. Warner Bros., Inc. for its visual art.

Plot

[edit]Kevin Lomax is a Gainesville, Florida, defense attorney who has never lost a case. While defending schoolteacher Lloyd Gettys against a charge of child molestation, he realizes that his client is guilty. Nevertheless, Kevin proceeds with his defense, destroying the victim's credibility through a harsh cross-examination and securing an acquittal for Gettys.

A New York City law firm asks Kevin to assist them with a jury selection. After the jury delivers a not-guilty verdict, the head of the firm, John Milton, offers Kevin a job, which he accepts. Kevin and his wife Mary Ann move to Manhattan. Kevin is soon working long hours and neglecting Mary Ann. Kevin's Christian fundamentalist mother Alice, whose only sex was to conceive Kevin, urges the couple to return to Florida after meeting Milton. Kevin refuses.

Kevin is assigned to represent billionaire Alex Cullen, who is accused of murdering his wife, his stepson and a maid. As a result, Kevin sees even less of Mary Ann and fantasizes about his co-worker Christabella. Meanwhile, Mary Ann has visions of the partners' wives becoming demonic, and has a nightmare about a baby playing with her removed ovaries. After a doctor declares Mary Ann to be infertile, she begs Kevin that they return to Gainesville, but he refuses. Milton suggests that Kevin step down from the trial to care for Mary Ann, but Kevin thinks that he will resent her for costing the case for the firm.

Eddie Barzoon, the firm's managing partner, discovers Kevin's name on the firm's charter and believes that Kevin covets his job. Eddie threatens to inform the United States Attorney's office of the firm's dubious activities, and Kevin tells Milton. Although Milton seems to dismiss Kevin's concerns, Eddie is beaten to death in Central Park.

Preparing Melissa Black, Alex Cullen's secretary, to testify, Kevin realizes that she is lying to give Cullen a false alibi. He tells Milton that he thinks Alex is guilty, but Milton offers to support him anyway. Kevin proceeds, winning an acquittal with Melissa's perjured testimony. Afterward, Kevin finds Mary Ann in a nearby church covered with a blanket. She claims that Milton raped her that day, and shows Kevin her body covered with cuts and scratches. Knowing that Milton was in court with him, Kevin believes that she must have injured herself and admits her into a mental institution.

U.S. Justice Department agent Mitch Weaver warns Kevin that Milton is corrupt, and also reveals that Gettys, acquitted in Florida, has been arrested for killing a little girl. Moments later, Weaver is struck by a car and killed. At the same time, while attending Eddie's funeral service, Milton sticks his finger into holy water and makes it boil.

Kevin, his mother Alice, and his case manager Pam Garrety, visit Mary Ann at the institution. Envisioning Pam as a demon, Mary Ann hits her, barricades the room and kills herself. Alice reveals that Milton is Kevin's father. Kevin leaves the hospital to confront Milton, who admits to raping Mary Ann. Kevin shoots Milton, but the bullets do not harm him. Milton reveals that he is Satan.

Kevin blames Milton for everything that happened, but Milton points out that he merely "set the stage". It was Kevin who chose to neglect his wife and defend people who he knew were guilty. Kevin realizes that he always wanted to win, regardless of the cost. Christabella appears; Milton announces that he wants Kevin and Christabella (Kevin's half-sister) to conceive the Antichrist. Kevin initially appears to acquiesce but abruptly shoots himself in the head. Milton's demonic rage burns Christabella alive, revealing his demonic form before turning into a winged angel that resembles Kevin.

Suddenly, Kevin is again at the Gainesville courthouse during the recess of the Gettys trial. The entire experience was a vision. Kevin returns to the courtroom and sees that Mary Ann is alive and well. When the trial resumes, Kevin announces that he cannot represent his client, despite the risk of disbarment. Kevin's reporter friend Larry offers to do a high-profile interview with him, promising to make him famous. Encouraged by Mary Ann, Kevin agrees.

After they leave, Larry transforms into Milton, who breaks the fourth wall and declares, "Vanity—definitely my favorite sin".

Cast

[edit]- Keanu Reeves as Kevin Lomax

- Al Pacino as John Milton / Satan

- Charlize Theron as Mary Ann Lomax

- Jeffrey Jones as Eddie Barzoon

- Judith Ivey as Alice Lomax

- Connie Nielsen as Christabella Andreoli

- Craig T. Nelson as Alexander Cullen

- Heather Matarazzo as Barbara

- Tamara Tunie as Jackie Heath

- Murphy Guyer as Barbara's Father

- Ruben Santiago-Hudson as Leamon Heath

- Michael Lombard as Judge Poe

- Debra Monk as Pam Garrety

- Vyto Ruginis as Mitch Weaver, Justice Department

- Laura Harrington as Melissa Black

- Pamela Gray as Diana Barzoon

- Mohammad B. Ghaffari (as M. B. Ghaffari) as Bashir Toabal

- George Wyner as Meisel

- Neal Jones as Larry, a Florida reporter

- Don King as himself[3]

- Roy Jones Jr. as himself (uncredited)[4]

- Delroy Lindo as Phillipe Moyez (uncredited)[5]

- Chris Bauer as Lloyd Gettys

- Monica Keena as Alessandra Cullen

- Senator Al D'Amato as himself[3]

- Harsh Nayyar as Parvathi Resh

Themes and interpretations

[edit]The Devil character's name is a direct homage to John Milton, who wrote Paradise Lost,[6] quoted by Lomax with the line, "Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heav'n".[7] Despite this, the thrust of Milton's epic was to rebuke the devil.[8] As a rebel against God, complaining of being perpetually "underestimated", the Milton character, like Paradise Lost's Satan, is "Heav'n running from Heav'n" with a "sense of injur'd merit".[9]

Professor Eric C. Brown judges the climax, in which Milton attempts to persuade Lomax to have sex with his half-sister to conceive the Antichrist, to be the most "Miltonic", as the sculptures become animated in carnal activities evoking Paradise Lost's "Downfall of the Rebel Angels".[7] The tirade that Milton gives in this sequence is also reminiscent of Satan's lines in Paradise Lost, Books I and II.[10] In U.S. literary education, Milton's temptation of Lomax in the climax, in which he rationalizes rebellion against God for a "look-but-don't-touch" model, has been compared to Satan urging Eve to eat forbidden fruit in Paradise Lost, Book IX, lines 720–730:[11]

If they all things, who enclos'd Knowledge of good and evil in this tree, That whoso eats thereof forthwith attains Wisdom without their leave? and wherein lies Th' offence, that Man should thus attain to know?

In his DVD commentary, Taylor Hackford did not name Paradise Lost as an inspiration, instead citing the legend of Faust.[12] An underlying concept of the story is a "Faustian bargain", offered to a character with free will.[13] Philosopher Peter van Inwagen writes that Milton referring to free will as a "bitch" when Lomax contemplates selling his soul moves away from a legalistic definition of "free will" as "uncoerced" into the philosophical realm of its definition.[14]

As with Goethe's Faust, the Devil that is commonly depicted in cinema is associated with lust and temptation.[15] Milton shows Lomax many seductive women to induce his "fall". Sex or rape is usually also the means by which Satan creates the Antichrist, as in Roman Polanski's 1968 film Rosemary's Baby. In The Devil's Advocate, someone other than Satan will have sex to conceive the Antichrist, although Milton nevertheless brutally rapes Mary Ann.[15] Incest becomes a way of creating the Antichrist, for the offspring of Satan's son and daughter will inherit much of Satan's genetic makeup.[6]

Dante Alighieri's Inferno raised "visual potential" that informed the film.[16] Dantean scholar Amilcare A. Iannucci argues that the plot follows the model of the Divine Comedy in beginning with selva oscura, with Lomax losing his conscience defending a guilty man, and entering and exploring deeper circles of Hell.[17]

Iannucci compares the office building structure to the circles, listing fireplaces where flames are always present; demonic visual phenomena; and water outside of Milton's office, analogized to Dante's Satan's icy home, albeit situated at the top of Hell, as opposed to the bottom.[18] Free will is also a major theme in the Divine Comedy, with the film's musings on the concept being similar to Dante's Purgatorio, 16.82–83 ("if the present world has gone astray, in you is the cause, in you it's to be sought").[19]

Other religious references are present. In describing New York City as Babylon, Alice Lomax invokes Revelation 18:[20]

Babylon the great is fallen, is fallen, and has become a dwelling place of demons, a prison for every foul spirit, and a cage for every unclean and hated bird!

Milton tempting Lomax is also possibly inspired by the Biblical Temptation of Christ.[6] Aside from Milton, other character names have been commented on: Author Kelly J. Wyman matches Mary Ann, the virginal figure who falls victim to Milton, to the Virgin Mary, and adds the literal translation of Christabella is "Beautiful Christ",[21] and that the title refers to the Catholic Church's Devil's advocates and lawyers as advocates;[22] Eric C. Brown finds Barzoon's name and character to be reminiscent of the demon prince Beelzebub.[7] Scholars Miguel A. De La Torre and Albert Hernández observe the vision of Satan as CEO, wearing expensive clothing and engaging in business, had appeared in popular culture before, including the 1942 novel The Screwtape Letters.[23]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Andrew Neiderman wrote The Devil's Advocate as a novel, and it was published in 1990 by Simon and Schuster.[24] Believing that his story could be adapted into a film, Neiderman approached Warner Bros. and claimed to have led his successful sale with the synopsis, "It's about a law firm in New York that represents only guilty people, and never loses".[25]

Various screenplay adaptations of The Devil's Advocate had been pitched to U.S. cinema studios, with Joel Schumacher planned to direct it, with Brad Pitt as the young lawyer.[26] Schumacher planned a sequence in which Pitt would descend into the New York subway system that would be modeled on the circles of hell in Dante's Divine Comedy.[27] With no actor to play Satan, this project collapsed.[26]

The O.J. Simpson murder trial and its controversial outcome gave new impetus to relaunching the project, with a $60 million budget.[26] Warner Bros. hired Taylor Hackford to direct the new attempt.[27] The director embraced the legal drama aspect, theorizing, "The courtroom has become the gladiator arena of the late twentieth century. Following the progress of a sensational trial is a spectator sport."[28]

Tony Gilroy led much of the rewrite with supervision by Hackford, who envisioned it as "a modern-day morality play" and "Faustian tale".[29] As the screenplay developed, free-will became a theme in which Milton does not actually cause events. Hackford wanted suggestions that Milton does not kill Barzoon as he defied his muggers, or United States Attorney Weaver, who arrogantly did not watch for vehicles before stepping onto the road.[30]

The screenwriters added the plot element that Lomax was Milton's son, and that Milton could produce the Antichrist, neither of which are in the novel.[31] Hackford cited the films Rosemary's Baby and The Omen as influences, and both had explored the Antichrist mythology.[12][31] Another change from the novel was converting the book's lesbian client to the pedophile Lloyd Gettys, avoiding undertones of homophobia.[32] In an early version of the screenplay, the "better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven" quotation is given to Milton rather than Lomax.[8]

Casting

[edit]Al Pacino had previously been offered the role of the Devil in an attempt to adapt Neiderman's novel, but before final rewrites, he rejected it on three occasions[29] because of the clichéd nature of the character.[26] Pacino suggested Robert Redford and Sean Connery for the role.[33] Keanu Reeves chose to star in The Devil's Advocate instead of Speed 2, despite a promised $11 million for the sequel to his 1994 hit Speed.[29] According to Reeves's staff, the actor was averse to performing in two consecutive action films after Chain Reaction (1996).[34] On The Devil's Advocate, Reeves agreed to a pay cut worth millions of dollars so that the producers could meet Pacino's salary demands.[35] To prepare for the role, Pacino watched the 1941 film The Devil and Daniel Webster and observed tips from Walter Huston as Mr. Scratch. He also read Dante's Inferno and Paradise Lost.[26]

Connie Nielsen, a Danish actress, was selected by Hackford for Christabella, who speaks several languages, with Hackford asserting that Nielsen already spoke multiple languages.[30] Craig T. Nelson was cast against type in a villainous role.[30]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography began in New York in 1996, but struggled by November. Delays were caused by the dismissals of the original cinematographer and assistant directors, while an anonymous source claimed that Pacino found Hackford to be conceited and loud.[27] An executive alleged that Pacino was typically late to work, although producer Arnold Kopelson said that this was not the case.[27] Hackford said that Pacino was professional, although his status meant that he did not need to be.[36]

Production designer Bruno Rubeo was tasked to create Milton's apartment, aiming for a "very loose and very sexy" appearance, "so you can't really tell where it goes".[37] Hackford said on this set that he encouraged Reeves and Pacino to "feel the room" and develop some improvisation.[38] Pacino came up with the idea of dancing to "It Happened in Monterey" by Frank Sinatra, and Hackford immediately adopted the idea.[36]

When Lomax leaves to meet Milton, he walks on 57th Street in New York, abnormally devoid of people or vehicles. It was shot on the actual 57th Street, with the filmmakers having it emptied at 7:30 a.m. on a Sunday.[30] The offices were shot at the Continental Club in Manhattan, and at the Continental Plaza, although the water outside of Milton's office was added later by computer effects.[37] In constructing the firm sets, Hackford and Rubeo consulted architects from Japan and Italy to craft an "ultra-modern" look, to display Milton's taste.[30] Donald Trump's penthouse in Trump Tower, Fifth Avenue, was lent to the production for Alexander Cullen's residence.[37][39]

A number of churches and courts hosted production. The interior of New York City's Church of the Heavenly Rest was used for the scene in which Theron's character says that Milton raped her.[29][39] The outside of Central Presbyterian Church was photographed for Barzoon's funeral, while Pacino was inside the Manhattan Church of the Most Holy Redeemer for the holy water sequence.[39] For court scenes, New Jersey's Bergen County Court House was employed for production,[40] as were historic courthouses in New York.[41]

After the completion of the New York shoot in March 1997, production moved to Florida in July 1997.[42] In Jacksonville, Florida, the interior of Mrs. Howard's business in Riverside and Avondale was used for New York scenes. Its co-owner Jim Howard remodeled the store and appeared as an extra.[42] The Gainesville church scenes were shot at a Gainesville church after Hackford persuaded the pastor and his members to participate, telling them that his story was about combating Satan.[30]

Theron had to briefly leave the United States while filming because she was working illegally.[43]

Post-production

[edit]At the end of the film, John Milton morphs into Lucifer as a fallen angel. The crew created the effect by combining life masks depicting Reeves, Pacino in 1997 and Pacino as he appeared in the 1972 film The Godfather.[44] The Godfather makeup artist Dick Smith supplied to The Devil's Advocate artist Rick Baker, Smith's former protégé, the life mask that he made in the 1970s.[45] Additionally, Baker created images for demonic faces seen on real actresses and actors, with hands also appearing to move underneath Tamara Tunie's skin, a digital creation with the contributions of Richard Greenberg and Stephanie Powell.[30]

Shots of ballerinas moving in water were used as a basis for Milton's animated sculpture.[30] Special-effects producer Edward L. Williams said that he filmed the people for the statue effect, and that they were naked and placed in a tank next to a blue screen.[46] It took three months to film the people and add the computer effects, at a cost of $2 million, which was 40% of the overall budget for special effects.[46]

James Newton Howard, a past collaborator with Hackford, was tasked to write the score.[47] Hackford dubbed Pacino's performance of "It Happened in Monterey" with Sinatra's voice.[38] "Paint It Black" by The Rolling Stones is also used for the film's conclusion.[48]

Release

[edit]During early stages of photography, Warner Bros. aspired to a release in August 1997.[27] The film eventually had its release on October 17, 1997,[26] on the same day as another horror film, I Know What You Did Last Summer.[49] To promote the release, Warner Bros.'s website included the warning on Hell's Gate from Dante's Inferno Canto III ("Abandon every hope, ye who enter here"), with credits presented as circles of Hell.[9] The television advertizing and poster were upfront regarding Milton being Satan, although it is not explicitly revealed in the film until its later acts.[50]

Approximately 475,000 copies of the VHS and DVD were produced by February 1998, but their release into the home-video market was delayed pending the Hart v. Warner Bros., Inc. lawsuit.[51] Afterward, he film went into regular airings on TNT and TBS.[52] In 2012, a Blu-ray edition was released in Region A as an "Unrated Director's Cut", in which the climax's art that was previously subject to the lawsuit is digitally redone.[53]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]On its opening weekend in October 1997, The Devil's Advocate earned $12.2 million, finishing second in the U.S. box office to I Know What You Did Last Summer, which made $16.1 million.[54] The Devil's Advocate was largely competing against thriller films aimed at youth in the Halloween season.[54] By December 6, 1997, it grossed $56.1 million.[55] It ended its run on February 12, 1998, with a gross of $61 million in North America and $92 million elsewhere.[56]

Critical response

[edit]Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes assigned the film an approval rating of 63%, based on 62 reviews, with an average rating of 6.3/10. The site's critics consensus states: "Though it is ultimately somewhat undone by its own lofty ambitions, The Devil's Advocate is a mostly effective blend of supernatural thrills and character exploration."[57] Metacritic gives the film a weighted average score of 60 out of 100, based on 19 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[58] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B" on a scale of A+ to F.[59]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote, "The movie never fully engaged me; my mind raced ahead of the plot, and the John Grisham stuff clashed with the Exorcist stuff."[50]

In The New York Times, Janet Maslin complimented the "gratifyingly light touch" of using John Milton's name, and special effects with "gimmicks well tethered to reality".[60]

David Denby wrote in New York magazine that The Devil's Advocate was "preposterously entertaining" and predicted that it would get viewers debating.[61]

Entertainment Weekly gave it a B, with Owen Gleiberman declaring it "at once silly, overwrought, and almost embarrassingly entertaining", and crediting Pacino for his performance.[62] Gleiberman later declared that Pacino had won the magazine's yearly award for Best Overacting.[63]

Variety's Todd McCarthy declared it "fairly entertaining", displaying "a nearly operatic sense of absurdity and excess".[3]

Dave Kehr of New York Daily News also preferred Pacino over Reeves, assessing that The Devil's Advocate as Faust moved to Manhattan, although disappointed that a "witty undercurrent becomes an exaggerated moralism".[64] Critic James Berardinelli wrote that it "is a highly enjoyable motion picture that's part character study, part supernatural thriller, and part morality play".[65]

In The New York Times Magazine, Michiko Kakutani objected to trivializing Satan, reducing Paradise Lost's vision of the War in Heaven to "an extended lawyer joke".[66]

The Christian Science Monitor's David Sterritt wrote that it is an unsurprising cinematic re-imagining of Faust with Satan a lawyer, but he recognized its message of "the need for personal responsibility", albeit with "more lascivious sex and shocking violence than a traditional 'Faust' rendition".[67]

In 2014, Yahoo! named The Devil's Advocate as "Pacino's Most Underrated Film", claiming that "Pacino's hammy devil never got his due", but, "there's something to be said for an actor who can pull off this level of theatrics".[68]

In his 2015 Movie Guide, Leonard Maltin gives it three stars, finding Reeves credible and Pacino "delicious".[69]

Scott Mendelson wrote in Forbes in 2015, "I love this trashy, vulgar, unapologetically puritan melodrama more than I care to admit."[49]

In 2016, The Huffington Post reported on an online debate over the possible symbolism in the costume design, as Lomax appears in suits that are light in the beginning, becoming increasingly darker as his morality slips away. The counterpoint is that this merely reflects his increasing social status.[70]

Accolades

[edit]The film won the Saturn Award for Best Horror Film.[71] Pacino was also nominated for the MTV Movie Award for Best Villain.[72]

Legacy

[edit]Lawsuit

[edit]The film was the subject of legal action in Hart v. Warner Bros., Inc. in 1997. The claim was that the sculpture featuring human forms in John Milton's apartment closely resembled the Ex nihilo sculpture by Frederick Hart on the facade of the Episcopal National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., and that a scene involving the sculpture infringed Hart's rights under copyright law in the United States.[73] Hart and the National Cathedral jointly initiated the action, with an argument similar to architect Lebbeus Woods's successful lawsuit over imagery in the film 12 Monkeys.[55] Defenses available to Warner Bros. were that the effect was designed without knowledge of Ex nihilo, or fair use.[55]

After a federal judge ruled that the film's video release would be delayed until the case went to trial unless a settlement was reached, Warner Bros. agreed to edit the scene for future releases and to attach stickers to unedited videotapes to indicate there was no relation between the art in the film and Hart's work.[74] The settlement in February 1998 meant 475,000 copies of the VHS and DVD could go into rental stores and businesses.[51]

Adaptations

[edit]In 2014, Andrew Neiderman wrote a prequel novel, Judgment Day, about John Milton arriving in New York City and obtaining control of a major law firm. Neiderman brought the book to Warner Bros. for a television series adaptation.[75] John Wells and Arnold Kopelson unsuccessfully attempted to adapt Devil's Advocate into a series in 2014.[76] Produced by Warner Bros. Television,[77] Wells and Kopelson took the project to NBC for a television pilot written by Matt Venne.[76]

A musical play based on The Devil's Advocate is[as of?] in development[citation needed]. Julian Woolford also launched a stage adaptation Advocaat van de Duivel in the Netherlands in 2015.[78]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Devil's Advocate (18)". British Board of Film Classification. October 31, 1997. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Devil's Advocate (1997)". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c McCarthy, Todd (October 10, 1997). "Review: 'The Devil's Advocate'". Variety. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Stroud, Matthew (September 23, 2009). "Filmmaker brings stories and opportunities back home". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Walston, Brandon K. (October 24, 1997). "Pacino Steals the Show in 'Advocate'". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c Fry 2008, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b c Brown 2006, p. 93.

- ^ a b Netzley 2006, p. 114.

- ^ a b Iannucci 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Netzley 2006, p. 116.

- ^ Webb 2007, p. 126.

- ^ a b Netzley 2006, p. 115.

- ^ Brown 2006, pp. 91–92.

- ^ van Inwagen 2017, p. 151.

- ^ a b Wyman 2009, p. 303.

- ^ Iannucci 2004, p. x.

- ^ Iannucci 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Iannucci 2004, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Iannucci 2004, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Brown 2006, p. 92.

- ^ Wyman 2009, p. 307.

- ^ Wyman 2009, pp. 307–308.

- ^ De La Torre & Hernández 2011, p. 14.

- ^ Netzley 2006, p. 123.

- ^ TDS (May 23, 2014). "Author Andrew Neiderman enjoys literary, TV success". The Desert Sun. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Mathews, Jack (October 15, 1997). "Jumping into the Fire: In 'Advocate,' Al Pacino takes a walk on the dark side. Luckily, he's no stranger to these mean streets". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Brennan, Judy (November 27, 1996). "On Pacino Film, They're Having Devil of a Time". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ Levi 2005, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d Hamill, Denis (February 16, 1997). "Eye On Evil In 'Devil's Advocate,' Taylor Hackford Takes Satan To Court". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hackford, Taylor (1998). The Devil's Advocate audio commentary (DVD). Warner Home Video.

- ^ a b Schoell 2016, p. 113.

- ^ Schoell 2016, p. 112: "In the novel the pedophile client was a woman, a lesbian, and it was strongly implied that she was guilty, although many of the characters seemed to think it was bad enough that she was a lesbian."

- ^ "See the Cast of 'The Devil's Advocate' then and Now". February 22, 2014.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (June 14, 1996). "'Speed' bump". Entertainment Weekly. No. 331. p. 7.

- ^ "Keanu Gives Up 'Matrix' Money". ABC News. September 10, 1999. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Grobel 2008, p. xxxii.

- ^ a b c Rubeo, Bruno (1998). "On Location". The Devil's Advocate (DVD). Warner Home Video.

- ^ a b Guerrasio, Jason (February 1, 2017). "This Oscar-winning director reveals the secrets of working with De Niro and Pacino". Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c Ocker 2012, p. 200.

- ^ "History of the Bergen County Courthouse". Bergen County Sheriff's Office. 2017. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Ocker 2012, p. 199.

- ^ a b "'Devil's Advocate' brings Keanu Reeves to Florida". The Florida Times-Union. Jacksonville, Florida. July 6, 1997. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "Theron Thrown Out Of America While Filming Devil's Advocate". Contactmusic.com. WENN. September 16, 2009. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Hackford, Taylor (1998). "Special Effects". The Devil's Advocate (DVD). Warner Home Video.

- ^ Robb 2003, p. 144.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Deborah (March 2000). "His effects are truly special". Black Enterprise. p. 66.

- ^ Heine 2016, p. 7.

- ^ Kubernik 2006, p. 46.

- ^ a b Mendelson, Scott (October 13, 2015). "'Halloween,' 'Saw II' And The 10 Biggest Horror Hits of October". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (October 17, 1997). "Devil's Advocate". Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago, Illinois: Sun-Times Media Group. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Stern, Christopher (February 16, 1998). "Settlement reached in 'Devil's Advocate' case". Variety. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ Netzley 2006, p. 113.

- ^ Spurlin, Thomas (September 22, 2012). "The Devil's Advocate (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Associated Press (October 20, 1997). "'I Know What You Did' Scares Up Big Box Office". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c Masters, Brooke A. (December 6, 1997). "Sculptor, Cathedral Sue Over Movie's Art". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ "The Devil's Advocate (1997)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ "The Devil's Advocate (1997)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. October 17, 1997. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ "The Devil's Advocate reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on August 11, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "Find CinemaScore" (Type "Devil's Advocate" in the search box). CinemaScore. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (October 17, 1997). "Film Review; Joining Evil, Esq., At Satan & Satan". The New York Times. Vol. 147, no. 50948. New York City. p. E12. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Denby, David (October 27, 1997). "Satan Place". New York. New York City: New York Media. p. 80.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (October 24, 1997). "Satanic versus". Entertainment Weekly. No. 402. New York City: Meredith Corporation. p. 40. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (December 26, 1997). "Best & Worst / Movie Campaigns". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (October 17, 1997). "Movie Review: 'The Devil's Advocate'". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (1997). "The Devil's Advocate". Reelviews. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (December 7, 1997). "To hell with him". New York Times Magazine. Vol. 147, no. 50999. New York City: New York Times Company. p. 36. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ Sterritt, David (October 20, 1997). "'Devil's Advocate' falls into 'Sin-and-Scripture syndrome'". The Christian Science Monitor. Vol. 89, no. 227. p. 15. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ "Why 'The Devil's Advocate' Is Pacino's Most Underrated Film". Yahoo!. December 5, 2014. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Maltin 2014.

- ^ Bradley, Bill (April 28, 2016). "This Will Totally Change How You See 'The Devil's Advocate'". The Huffington Post. New York City: Huffington Post Media Group. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ "Past Saturn Award Recipients". Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Katz, Richard (April 14, 1998). "MTV-watchers pick their pix". Variety. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Niebuhr, Gustav (December 5, 1997). "Sculpture in a Movie Leads to Suit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ "Film studio settles claim over copyrighted sculpture". Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. February 23, 1998. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ Remling, Amanda (April 12, 2014). "Author Andrew Neiderman Talks About V.C. Andrews's Future, 'Devil's Advocate' Prequel And More". International Business Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Andreeva, Nellie (August 18, 2014). "NBC Developing 'The Devil's Advocate' Drama Series Produced By John Wells & Arnold Kopelson". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ Hibberd, James (August 18, 2014). "'Devil's Advocate' TV series in development at NBC". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ "'Advocaat van de Duivel' in De Reeehorst". Ede Stad (in Dutch). Ede, Netherlands. November 25, 2015. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brown, Eric C. (2006). "Popularizing Pandaemonium: Milton and the Horror Film". In L. Knoppers; G. Colón Semenza; Gregory M. Colón Semenza (eds.). Milton in Popular Culture. Springer. ISBN 1-40398318-6.

- De La Torre, Miguel A.; Hernández, Albert (2011). The Quest for the Historical Satan. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-45141481-3.

- Fry, Carrol Lee (2008). Cinema of the Occult: New Age, Satanism, Wicca, and Spiritualism in Film. Bethlehem: Lehigh University Press. ISBN 978-0-93422395-9.

- Grobel, Lawrence (2008). Al Pacino. New York, London, Toronto and Sydney: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-41695556-6.

- Heine, Erik (2016). James Newton Howard's Signs: A Film Score Guide. Lanham, Boulder, NY and London: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-144225604-0.

- Iannucci, Amilcare A. (2004). Dante, Cinema, and television. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-80208827-9.

- Kubernik, Harvey (2006). Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music in Film and on Your Screen. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-82633542-X.

- Levi, Ross D. (2005). The Celluloid Courtroom: A History of Legal Cinema. Westport, CT and London: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-27598233-5.

- Maltin, Leonard (2014). Leonard Maltin's 2015 Movie Guide. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-69818361-2.

- Netzley, Ryan (2006). "'Better To Reign in Hell Than Serve in Heaven, Is That It?': Ethics, Apocalypticism, and Allusion in The Devil's Advocate". In L. Knoppers; G. Colón Semenza; Gregory M. Colón Semenza (eds.). Milton in Popular Culture. Springer. ISBN 1-40398318-6.

- Ocker, J. W. (2012). The New York Grimpendium: A Guide to Macabre and Ghastly Sites in New York State. Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press. ISBN 978-1-58157772-3.

- Robb, Brian J. (2003). Keanu Reeves: An Excellent Adventure (2 ed.). Plexus Publishing. ISBN 0-85965313-7.

- Schoell, William (2016). Al Pacino: In Films and on Stage (2nd ed.). Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-78647196-6.

- van Inwagen, Peter (2017). Thinking about Free Will. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10716650-9.

- Webb, Rebecca K. (2007). A Conflict of Paradigms: Social Epistemology and the Collapse of Literary Education. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-73911755-2.

- Wyman, Kelly J. (2009). "Satan in the Movies". The Continuum Companion to Religion and Film. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-82649991-2.

External links

[edit]- 1997 films

- 1990s supernatural horror films

- 1997 horror films

- American supernatural horror films

- American courtroom films

- Demons in film

- 1990s English-language films

- Films about lawyers

- Films based on American horror novels

- Films directed by Taylor Hackford

- Films produced by Arnold Kopelson

- Films scored by James Newton Howard

- Films with screenplays by Tony Gilroy

- Films set in Florida

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in Florida

- Films shot in New Jersey

- Films shot in New York City

- American horror thriller films

- American legal thriller films

- Legal horror films

- Regency Enterprises films

- Films about Satanism

- Supernatural drama films

- The Devil in film

- Warner Bros. films

- Works subject to a lawsuit

- Films produced by Arnon Milchan

- 1990s American films

- 1990s legal thriller films

- American religious horror films

- Saturn Award–winning films

- English-language horror films

- English-language thriller films