Death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism.[1] The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose shortly after death.[2] Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. Some organisms, such as Turritopsis dohrnii, are biologically immortal; however, they can still die from means other than aging.[3] Death is generally applied to whole organisms; the equivalent for individual components of an organism, such as cells or tissues, is necrosis.[4] Something that is not considered an organism, such as a virus, can be physically destroyed but is not said to die, as a virus is not considered alive in the first place.[5]

As of the early 21st century, 56 million people die per year. The most common reason is aging,[6] followed by cardiovascular disease, which is a disease that affects the heart or blood vessels.[7] As of 2022, an estimated total of almost 110 billion humans have died, or roughly 94% of all humans to have ever lived.[8] A substudy of gerontology known as biogerontology seeks to eliminate death by natural aging in humans, often through the application of natural processes found in certain organisms.[9] However, as humans do not have the means to apply this to themselves, they have to use other ways to reach the maximum lifespan for a human, often through lifestyle changes, such as calorie reduction, dieting, and exercise.[10] The idea of lifespan extension is considered and studied as a way for people to live longer.

Determining when a person has definitively died has proven difficult. Initially, death was defined as occurring when breathing and the heartbeat ceased, a status still known as clinical death.[11] However, the development of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) meant that such a state was no longer strictly irreversible.[12] Brain death was then considered a more fitting option, but several definitions exist for this. Some people believe that all brain functions must cease. Others believe that even if the brainstem is still alive, the personality and identity are irretrievably lost, so therefore, the person should be considered entirely dead.[13] Brain death is sometimes used as a legal definition of death.[14] For all organisms with a brain, death can instead be focused on this organ.[15][16] The cause of death is usually considered important and an autopsy can be done. There are many causes, from accidents to diseases.

Many cultures and religions have a concept of an afterlife that may hold the idea of judgment of good and bad deeds in one's life. There are also different customs for honoring the body, such as a funeral, cremation, or sky burial.[17] After a death, an obituary may be posted in a newspaper, and the "survived by" kin and friends usually go through the grieving process.

Diagnosis

Problems of definition

The concept of death is the key to human understanding of the phenomenon.[18] There are many scientific approaches and various interpretations of the concept. Additionally, the advent of life-sustaining therapy and the numerous criteria for defining death from both a medical and legal standpoint have made it difficult to create a single unifying definition.[19]

Defining life to define death

One of the challenges in defining death is in distinguishing it from life. As a point in time, death seems to refer to the moment when life ends. Determining when death has occurred is difficult, as cessation of life functions is often not simultaneous across organ systems.[20] Such determination, therefore, requires drawing precise conceptual boundaries between life and death. This is difficult due to there being little consensus on how to define life.

It is possible to define life in terms of consciousness. When consciousness ceases, an organism can be said to have died. One of the flaws in this approach is that there are many organisms that are alive but probably not conscious.[21] Another problem is in defining consciousness, which has many different definitions given by modern scientists, psychologists and philosophers.[22] Additionally, many religious traditions, including Abrahamic and Dharmic traditions, hold that death does not (or may not) entail the end of consciousness. In certain cultures, death is more of a process than a single event. It implies a slow shift from one spiritual state to another.[23]

Other definitions for death focus on the character of cessation of organismic functioning and human death, which refers to irreversible loss of personhood. More specifically, death occurs when a living entity experiences irreversible cessation of all functioning.[24] As it pertains to human life, death is an irreversible process where someone loses their existence as a person.[24]

Definition of death by heartbeat and breath

Historically, attempts to define the exact moment of a human's death have been subjective or imprecise. Death was defined as the cessation of heartbeat (cardiac arrest) and breathing,[11] but the development of CPR and prompt defibrillation have rendered that definition inadequate because breathing and heartbeat can sometimes be restarted.[12] This type of death where circulatory and respiratory arrest happens is known as the circulatory definition of death (CDD). Proponents of the CDD believe this definition is reasonable because a person with permanent loss of circulatory and respiratory function should be considered dead.[25] Critics of this definition state that while cessation of these functions may be permanent, it does not mean the situation is irreversible because if CPR is applied fast enough, the person could be revived.[25] Thus, the arguments for and against the CDD boil down to defining the actual words "permanent" and "irreversible," which further complicates the challenge of defining death. Furthermore, events causally linked to death in the past no longer kill in all circumstances; without a functioning heart or lungs, life can sometimes be sustained with a combination of life support devices, organ transplants, and artificial pacemakers.

Brain death

Today, where a definition of the moment of death is required, doctors and coroners usually turn to "brain death" or "biological death" to define a person as being dead;[26] people are considered dead when the electrical activity in their brain ceases.[27] It is presumed that an end of electrical activity indicates the end of consciousness.[28] Suspension of consciousness must be permanent and not transient, as occurs during certain sleep stages, and especially a coma.[29] In the case of sleep, electroencephalograms (EEGs) are used to tell the difference.[30]

The category of "brain death" is seen as problematic by some scholars. For instance, Dr. Franklin Miller, a senior faculty member at the Department of Bioethics, National Institutes of Health, notes: "By the late 1990s... the equation of brain death with death of the human being was increasingly challenged by scholars, based on evidence regarding the array of biological functioning displayed by patients correctly diagnosed as having this condition who were maintained on mechanical ventilation for substantial periods of time. These patients maintained the ability to sustain circulation and respiration, control temperature, excrete wastes, heal wounds, fight infections and, most dramatically, to gestate fetuses (in the case of pregnant "brain-dead" women)."[31]

While "brain death" is viewed as problematic by some scholars, there are proponents of it[who?] that believe this definition of death is the most reasonable for distinguishing life from death. The reasoning behind the support for this definition is that brain death has a set of criteria that is reliable and reproducible. Also, the brain is crucial in determining our identity or who we are as human beings. The distinction should be made that "brain death" cannot be equated with one in a vegetative state or coma, in that the former situation describes a state that is beyond recovery.[32]

EEGs can detect spurious electrical impulses, while certain drugs, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, or hypothermia can suppress or even stop brain activity temporarily;[33] because of this, hospitals have protocols for determining brain death involving EEGs at widely separated intervals under defined conditions.[34]

Neocortical brain death

People maintaining that only the neo-cortex of the brain is necessary for consciousness sometimes argue that only electrical activity should be considered when defining death. Eventually, the criterion for death may be the permanent and irreversible loss of cognitive function, as evidenced by the death of the cerebral cortex. All hope of recovering human thought and personality is then gone, given current and foreseeable medical technology.[13] Even by whole-brain criteria, the determination of brain death can be complicated.

Total brain death

At present, in most places, the more conservative definition of death (irreversible cessation of electrical activity in the whole brain, as opposed to just in the neo-cortex) has been adopted. One example is the Uniform Determination Of Death Act in the United States.[35] In the past, the adoption of this whole-brain definition was a conclusion of the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research in 1980.[36] They concluded that this approach to defining death sufficed in reaching a uniform definition nationwide. A multitude of reasons was presented to support this definition, including uniformity of standards in law for establishing death, consumption of a family's fiscal resources for artificial life support, and legal establishment for equating brain death with death to proceed with organ donation.[37]

Problems in medical practice

Aside from the issue of support of or dispute against brain death, there is another inherent problem in this categorical definition: the variability of its application in medical practice. In 1995, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) established the criteria that became the medical standard for diagnosing neurologic death. At that time, three clinical features had to be satisfied to determine "irreversible cessation" of the total brain, including coma with clear etiology, cessation of breathing, and lack of brainstem reflexes.[38] These criteria were updated again, most recently in 2010, but substantial discrepancies remain across hospitals and medical specialties.[38]

Donations

The problem of defining death is especially imperative as it pertains to the dead donor rule, which could be understood as one of the following interpretations of the rule: there must be an official declaration of death in a person before starting organ procurement, or that organ procurement cannot result in the death of the donor.[25] A great deal of controversy has surrounded the definition of death and the dead donor rule. Advocates of the rule believe that the rule is legitimate in protecting organ donors while also countering any moral or legal objection to organ procurement. Critics, on the other hand, believe that the rule does not uphold the best interests of the donors and that the rule does not effectively promote organ donation.[25]

Signs

Signs of death or strong indications that a warm-blooded animal is no longer alive are:[39]

- Respiratory arrest (no breathing)

- Cardiac arrest (no pulse)

- Brain death (no neuronal activity)

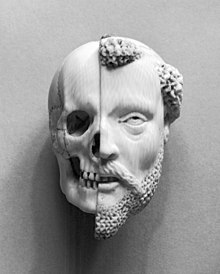

The stages that follow after death are:[40]

- Pallor mortis, paleness which happens in 15–120 minutes after death

- Algor mortis, the reduction in body temperature following death. This is generally a steady decline until matching ambient temperature

- Rigor mortis, the limbs of the corpse become stiff (Latin rigor) and difficult to move or manipulate

- Livor mortis, a settling of the blood in the lower (dependent) portion of the body

- Putrefaction, the beginning signs of decomposition

- Decomposition, the reduction into simpler forms of matter, accompanied by a strong, unpleasant odor.

- Skeletonization, the end of decomposition, where all soft tissues have decomposed, leaving only the skeleton.

- Fossilization, the natural preservation of the skeletal remains formed over a very long period

Legal

The death of a person has legal consequences that may vary between jurisdictions. Most countries follow the whole-brain death criteria, where all functions of the brain must have completely ceased. However, in other jurisdictions, some follow the brainstem version of brain death.[38] Afterward, a death certificate is issued in most jurisdictions, either by a doctor or by an administrative office, upon presentation of a doctor's declaration of death.[41]

Misdiagnosis

There are many anecdotal references to people being declared dead by physicians and then "coming back to life," sometimes days later in their coffin or when embalming procedures are about to begin. From the mid-18th century onwards, there was an upsurge in the public's fear of being mistakenly buried alive[42] and much debate about the uncertainty of the signs of death. Various suggestions were made to test for signs of life before burial, ranging from pouring vinegar and pepper into the corpse's mouth to applying red hot pokers to the feet or into the rectum.[43] Writing in 1895, the physician J.C. Ouseley claimed that as many as 2,700 people were buried prematurely each year in England and Wales, although some estimates peg the figure to be closer to 800.[44]

In cases of electric shock, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for an hour or longer can allow stunned nerves to recover, allowing an apparently dead person to survive. People found unconscious under icy water may survive if their faces are kept continuously cold until they arrive at an emergency room.[45] This "diving response," in which metabolic activity and oxygen requirements are minimal, is something humans share with cetaceans called the mammalian diving reflex.[45]

As medical technologies advance, ideas about when death occurs may have to be reevaluated in light of the ability to restore a person to vitality after longer periods of apparent death (as happened when CPR and defibrillation showed that cessation of heartbeat is inadequate as a decisive indicator of death). The lack of electrical brain activity may not be enough to consider someone scientifically dead. Therefore, the concept of information-theoretic death has been suggested as a better means of defining when true death occurs, though the concept has few practical applications outside the field of cryonics.[46]

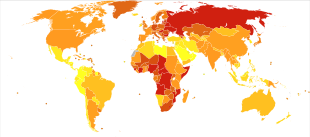

Causes

The leading cause of human death in developing countries is infectious disease. The leading causes in developed countries are atherosclerosis (heart disease and stroke), cancer, and other diseases related to obesity and aging. By an extremely wide margin, the largest unifying cause of death in the developed world is biological aging,[47] leading to various complications known as aging-associated diseases. These conditions cause loss of homeostasis, leading to cardiac arrest, causing loss of oxygen and nutrient supply, causing irreversible deterioration of the brain and other tissues. Of the roughly 150,000 people who die each day across the globe, about two thirds die of age-related causes.[47] In industrialized nations, the proportion is much higher, approaching 90%.[47] With improved medical capability, dying has become a condition to be managed.

In developing nations, inferior sanitary conditions and lack of access to modern medical technology make death from infectious diseases more common than in developed countries. One such disease is tuberculosis, a bacterial disease that killed 1.8 million people in 2015.[48] In 2004, malaria caused about 2.7 million deaths annually.[49] The AIDS death toll in Africa may reach 90–100 million by 2025.[50][51]

According to Jean Ziegler, the United Nations Special Reporter on the Right to Food, 2000 – Mar 2008, mortality due to malnutrition accounted for 58% of the total mortality rate in 2006. Ziegler says worldwide, approximately 62 million people died from all causes and of those deaths, more than 36 million died of hunger or diseases due to deficiencies in micronutrients.[52]

Tobacco smoking killed 100 million people worldwide in the 20th century and could kill 1 billion people worldwide in the 21st century, a World Health Organization report warned.[53]

Many leading developed world causes of death can be postponed by diet and physical activity, but the accelerating incidence of disease with age still imposes limits on human longevity. The evolutionary cause of aging is, at best, only beginning to be understood. It has been suggested that direct intervention in the aging process may now be the most effective intervention against major causes of death.[54]

Selye proposed a unified non-specific approach to many causes of death. He demonstrated that stress decreases the adaptability of an organism and proposed to describe adaptability as a special resource, adaptation energy. The animal dies when this resource is exhausted.[55] Selye assumed that adaptability is a finite supply presented at birth. Later, Goldstone proposed the concept of production or income of adaptation energy which may be stored (up to a limit) as a capital reserve of adaptation.[56] In recent works, adaptation energy is considered an internal coordinate on the "dominant path" in the model of adaptation. It is demonstrated that oscillations of well-being appear when the reserve of adaptability is almost exhausted.[57]

In 2012, suicide overtook car crashes as the leading cause of human injury deaths in the U.S., followed by poisoning, falls, and murder.[58]

Accidents and disasters, from nuclear disasters to structural collapses, also claim lives. One of the deadliest incidents of all time is the 1975 Banqiao Dam Failure, with varying estimates, up to 240,000 dead.[59] Other incidents with high death tolls are the Wanggongchang explosion (when a gunpowder factory ended up with 20,000 deaths),[60] a collapse of a wall of Circus Maximus that killed 13,000 people,[61] and the Chernobyl disaster that killed between 95 and 4,000 people.[62][63]

Natural disasters kill around 45,000 people annually, although this number can vary to millions to thousands on a per-decade basis. Some of the deadliest natural disasters are the 1931 China floods, which killed an estimated 4 million people, although estimates widely vary;[64] the 1887 Yellow River flood, which killed an estimated 2 million people in China;[65] and the 1970 Bhola cyclone, which killed as many as 500,000 people in Pakistan.[66] If naturally occurring famines are considered natural disasters, the Chinese famine of 1906–1907, which killed 15–20 million people, can be considered the deadliest natural disaster in recorded history.

In animals, predation can be a common cause of death. Livestock have a 6% death rate from predation. However, younger animals are more susceptible to predation. For example, 50% of young foxes die to birds, bobcats, coyotes, and other foxes as well. Young bear cubs in the Yellowstone National Park only have a 40% chance to survive to adulthood from other bears and predators.[67]

Autopsy

An autopsy, also known as a postmortem examination or an obduction, is a medical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a human corpse to determine the cause and manner of a person's death and to evaluate any disease or injury that may be present. It is usually performed by a specialized medical doctor called a pathologist.[68]

Autopsies are either performed for legal or medical purposes.[68] A forensic autopsy is carried out when the cause of death may be a criminal matter, while a clinical or academic autopsy is performed to find the medical cause of death and is used in cases of unknown or uncertain death, or for research purposes.[69] Autopsies can be further classified into cases where external examination suffices, and those where the body is dissected and an internal examination is conducted.[70] Permission from next of kin may be required for internal autopsy in some cases.[71] Once an internal autopsy is complete the body is generally reconstituted by sewing it back together.[40]

A necropsy, which is not always a medical procedure, was a term previously used to describe an unregulated postmortem examination. In modern times, this term is more commonly associated with the corpses of animals.[72]

Death before birth

Death before birth can happen in several ways: stillbirth, when the fetus dies before or during the delivery process; miscarriage, when the embryo dies before independent survival; and abortion, the artificial termination of the pregnancy. Stillbirth and miscarriage can happen for various reasons, while abortion is carried out purposely.

Stillbirth

Stillbirth can happen right before or after the delivery of a fetus. It can result from defects of the fetus or risk factors present in the mother. Reductions of these factors, caesarean sections when risks are present, and early detection of birth defects have lowered the rate of stillbirth. However, 1% of births in the United States end in a stillbirth.[73]

Miscarriage

A miscarriage is defined by the World Health Organization as, "The expulsion or extraction from its mother of an embryo or fetus weighing 500g or less." Miscarriage is one of the most frequent problems in pregnancy, and is reported in around 12–15% of all clinical pregnancies; however, by including pregnancy losses during menstruation, it could be up to 17–22% of all pregnancies. There are many risk-factors involved in miscarriage; consumption of caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, drugs, having a previous miscarriage, and the use of abortion can increase the chances of having a miscarriage.[74]

Abortion

An abortion may be performed for many reasons, such as pregnancy from rape, financial constraints of having a child, teenage pregnancy, and the lack of support from a significant other.[75] There are two forms of abortion: a medical abortion and an in-clinic abortion or sometimes referred to as a surgical abortion. A medical abortion involves taking a pill that will terminate the pregnancy no more than 11 weeks past the last period, and an in-clinic abortion involves a medical procedure using suction to empty the uterus; this is possible after 12 weeks, but it may be more difficult to find an operating doctor who will go through with the procedure.[76]

Senescence

Senescence refers to a scenario when a living being can survive all calamities but eventually dies due to causes relating to old age. Conversely, premature death can refer to a death that occurs before old age arrives, for example, human death before a person reaches the age of 75.[77] Animal and plant cells normally reproduce and function during the whole period of natural existence, but the aging process derives from the deterioration of cellular activity and the ruination of regular functioning. The aptitude of cells for gradual deterioration and mortality means that cells are naturally sentenced to stable and long-term loss of living capacities, even despite continuing metabolic reactions and viability. In the United Kingdom, for example, nine out of ten of all the deaths that occur daily relates to senescence, while around the world, it accounts for two-thirds of 150,000 deaths that take place daily.[78]

Almost all animals who survive external hazards to their biological functioning eventually die from biological aging, known in life sciences as "senescence." Some organisms experience negligible senescence, even exhibiting biological immortality. These include the jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii,[79] the hydra, and the planarian. Unnatural causes of death include suicide and predation. Of all causes, roughly 150,000 people die around the world each day.[47] Of these, two-thirds die directly or indirectly due to senescence, but in industrialized countries – such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany – the rate approaches 90% (i.e., nearly nine out of ten of all deaths are related to senescence).[47]

Physiological death is now seen as a process, more than an event: conditions once considered indicative of death are now reversible.[80] Where in the process, a dividing line is drawn between life and death depends on factors beyond the presence or absence of vital signs. In general, clinical death is neither necessary nor sufficient for a determination of legal death. A patient with working heart and lungs determined to be brain dead can be pronounced legally dead without clinical death occurring.[81]

Life extension

Life extension refers to an increase in maximum or average lifespan, especially in humans, by slowing or reversing aging processes through anti-aging measures. Aging is the most common cause of death worldwide. Aging is seen as inevitable, so according to Aubrey de Grey little is spent on research into anti-aging therapies, a phenomenon known as pro-aging trance.[47]

The average lifespan is determined by vulnerability to accidents and age or lifestyle-related afflictions such as cancer or cardiovascular disease. Extension of lifespan can be achieved by good diet, exercise, and avoidance of hazards such as smoking. Maximum lifespan is determined by the rate of aging for a species inherent in its genes. A recognized method of extending maximum lifespan is calorie restriction.[10] Theoretically, the extension of the maximum lifespan can be achieved by reducing the rate of aging damage, by periodic replacement of damaged tissues, molecular repair, or rejuvenation of deteriorated cells and tissues.[82]

A United States poll found religious and irreligious people, as well as men and women and people of different economic classes, have similar rates of support for life extension, while Africans and Hispanics have higher rates of support than white people. 38% said they would desire to have their aging process cured.[83]

Researchers of life extension can be known as "biomedical gerontologists." They try to understand aging, and develop treatments to reverse aging processes, or at least slow them for the improvement of health and maintenance of youthfulness.[9] Those who use life extension findings and apply them to themselves are called "life extensionists" or "longevists." The primary life extension strategy currently is to apply anti-aging methods to attempt to live long enough to benefit from a cure for aging.[84]

Cryonics

Cryonics (from Greek κρύος 'kryos-' meaning 'icy cold') is the low-temperature preservation of animals, including humans, who cannot be sustained by contemporary medicine, with the hope that healing and resuscitation may be possible in the future.[85][86]

Cryopreservation of people and other large animals is not reversible with current technology. The stated rationale for cryonics is that people who are considered dead by current legal or medical definitions, may not necessarily be dead according to the more stringent 'information-theoretic' definition of death.[46][87]

Some scientific literature is claimed to support the feasibility of cryonics.[88] Medical science and cryobiologists generally regard cryonics with skepticism.[89]

Location

Around 1930, most people in Western countries died in their own homes, surrounded by family, and comforted by clergy, neighbors, and doctors making house calls.[92] By the mid-20th century, half of all Americans died in a hospital.[93] By the start of the 21st century, only about 20 to 25% of people in developed countries died outside of a medical institution.[93][94][95] The shift from dying at home towards dying in a professional medical environment has been termed the "Invisible Death."[93] This shift occurred gradually over the years until most deaths now occur outside the home.[96]

Psychology

Death studies is a field within psychology.[97] To varying degrees people inherently fear death, both the process and the eventuality; it is hard wired and part of the 'survival instinct' of all animals.[98] Discussing, thinking about, or planning for their deaths causes them discomfort. This fear may cause them to put off financial planning, preparing a will and testament, or requesting help from a hospice organization.

Mortality salience is the awareness that death is inevitable. However, self-esteem and culture are ways to reduce the anxiety this effect can cause.[99] The awareness of someone's own death can cause a deepened bond in their in-group as a defense mechanism. This can also cause the person to become very judging. In a study, two groups were formed; one group was asked to reflect upon their mortality, the other was not, afterwards, the groups were told to set a bond for a prostitute. The group that did not reflect on death had an average of $50, the group who was reminded about their death had an average of $455.[100]

Different people have different responses to the idea of their deaths. Philosopher Galen Strawson writes that the death that many people wish for is an instant, painless, unexperienced annihilation.[101] In this unlikely scenario, the person dies without realizing it and without being able to fear it. One moment the person is walking, eating, or sleeping, and the next moment, the person is dead. Strawson reasons that this type of death would not take anything away from the person, as he believes a person cannot have a legitimate claim to ownership in the future.[101][102]

Society and culture

In society, the nature of death and humanity's awareness of its mortality has, for millennia, been a concern of the world's religious traditions and philosophical inquiry. Including belief in resurrection or an afterlife (associated with Abrahamic religions), reincarnation or rebirth (associated with Dharmic religions), or that consciousness permanently ceases to exist, known as eternal oblivion (associated with secular humanism).[103]

Commemoration ceremonies after death may include various mourning, funeral practices, and ceremonies of honoring the deceased.[104] The physical remains of a person, commonly known as a corpse or body, are usually interred whole or cremated, though among the world's cultures, there are a variety of other methods of mortuary disposal.[17] In the English language, blessings directed towards a dead person include rest in peace (originally the Latin, requiescat in pace) or its initialism RIP.

Death is the center of many traditions and organizations; customs relating to death are a feature of every culture around the world. Much of this revolves around the care of the dead, as well as the afterlife and the disposal of bodies upon the onset of death. The disposal of human corpses does, in general, begin with the last offices before significant time has passed, and ritualistic ceremonies often occur, most commonly interment or cremation. This is not a unified practice; in Tibet, for instance, the body is given a sky burial and left on a mountain top. Proper preparation for death and techniques and ceremonies for producing the ability to transfer one's spiritual attainments into another body (reincarnation) are subjects of detailed study in Tibet.[105] Mummification or embalming is also prevalent in some cultures to retard the rate of decay.[106] The rise of secularism resulted in material mementos of death declining.[107]

Some parts of death in culture are legally based, having laws for when death occurs, such as the receiving of a death certificate, the settlement of the deceased estate, and the issues of inheritance and, in some countries, inheritance taxation.[108]

Capital punishment is also a culturally divisive aspect of death. In most jurisdictions where capital punishment is carried out today, the death penalty is reserved for premeditated murder, espionage, treason, or as part of military justice. In some countries, sexual crimes, such as adultery and sodomy, carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes, such as apostasy, the formal renunciation of one's religion. In many retentionist countries, drug trafficking is also a capital offense. In China, human trafficking and serious cases of corruption are also punished by the death penalty. In militaries around the world, courts-martial have imposed death sentences for offenses such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny.[109] Mutiny is punishable by death in the United States.[110]

Death in warfare and suicide attacks also have cultural links, and the ideas of dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, which translates to "It is sweet and proper to die for one's country", is a concept that dates to antiquity.[110] Additionally, grieving relatives of dead soldiers and death notification are embedded in many cultures.[111] Recently in the Western world—with the increase in terrorism following the September 11 attacks but also further back in time with suicide bombings, kamikaze missions in World War II, and suicide missions in a host of other conflicts in history—death for a cause by way of suicide attack, including martyrdom, have had significant cultural impacts.[112]

Suicide, in general, and particularly euthanasia, are also points of cultural debate. Both acts are understood very differently in different cultures.[113] In Japan, for example, ending a life with honor by seppuku was considered a desirable death,[114] whereas according to traditional Christian and Islamic cultures, suicide is viewed as a sin.

Death is personified in many cultures, with such symbolic representations as the Grim Reaper, Azrael, the Hindu god Yama, and Father Time. In the west, the Grim Reaper, or figures similar to it, is the most popular depiction of death in western cultures.[116]

In Brazil, death is counted officially when it is registered by existing family members at a cartório, a government-authorized registry. Before being able to file for an official death, the deceased must have been registered for an official birth at the cartório. Though a Public Registry Law guarantees all Brazilian citizens the right to register deaths, regardless of their financial means of their family members (often children), the Brazilian government has not taken away the burden, the hidden costs, and fees of filing for a death. For many impoverished families, the indirect costs and burden of filing for a death lead to a more appealing, unofficial, local, and cultural burial, which, in turn, raises the debate about inaccurate mortality rates.[117]

Talking about death and witnessing it is a difficult issue in most cultures. Western societies may like to treat the dead with the utmost material respect, with an official embalmer and associated rites.[106] Eastern societies (like India) may be more open to accepting it as a fait accompli, with a funeral procession of the dead body ending in an open-air burning-to-ashes.[118]

Origins of death

The origin of death is a theme or myth of how death came to be. It is present in nearly all cultures across the world, as death is a universal happening.[119] This makes it an origin myth, a myth that describes how a feature of the natural or social world appeared.[120][121] There can be some similarities between myths and cultures. In North American mythology, the theme of a man who wants to be immortal and a man who wants to die can be seen across many Indigenous people.[122] In Christianity, death is the result of the fall of man after eating the fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.[119] In Greek mythology, the opening of Pandora's box releases death upon the world.[123]

Consciousness

Much interest and debate surround the question of what happens to one's consciousness as one's body dies. The belief in the permanent loss of consciousness after death is often called eternal oblivion. The belief that the stream of consciousness is preserved after physical death is described by the term afterlife.

Near-death experiences (NDEs) describe the subjective experiences associated with impending death. Some survivors of such experiences report it as "seeing the afterlife while they were dying". Seeing a being of light and talking with it, life flashing before the eyes, and the confirmation of cultural beliefs of the afterlife are common themes in NDEs.[124]

In biology

After death, the remains of a former organism become part of the biogeochemical cycle, during which animals may be consumed by a predator or a scavenger.[125] Organic material may then be further decomposed by detritivores, organisms that recycle detritus, returning it to the environment for reuse in the food chain, where these chemicals may eventually end up being consumed and assimilated into the cells of an organism.[126] Examples of detritivores include earthworms, woodlice, and millipedes.[127]

Microorganisms also play a vital role, raising the temperature of the decomposing matter as they break it down into yet simpler molecules.[128] Not all materials need to be fully decomposed. Coal, a fossil fuel formed over vast tracts of time in swamp ecosystems, is one example.[129]

Natural selection

The contemporary evolutionary theory sees death as an important part of the process of natural selection. It is considered that organisms less adapted to their environment are more likely to die, having produced fewer offspring, thereby reducing their contribution to the gene pool. Their genes are thus eventually bred out of a population, leading at worst to extinction and, more positively, making the process possible, referred to as speciation. Frequency of reproduction plays an equally important role in determining species survival: an organism that dies young but leaves numerous offspring displays, according to Darwinian criteria, much greater fitness than a long-lived organism leaving only one.[130][131]

Death also has a role in competition, where if a species out-competes another, there is a risk of death for the population, especially in the case where they are directly fighting over resources.[132]

Extinction

Death plays a role in extinction, the cessation of existence of a species or group of taxa, reducing biodiversity, due to extinction being generally considered to be the death of the last individual of that species (although the capacity to breed and recover may have been lost before this point). Because a species' potential range may be very large, determining this moment is difficult, and is usually done retrospectively.[134]

Evolution of aging and mortality

Inquiry into the evolution of aging aims to explain why so many living things and the vast majority of animals weaken and die with age. However, there are exceptions, such as Hydra and the jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii, which research shows to be biologically immortal.[135]

Organisms showing only asexual reproduction, such as bacteria, some protists, like the euglenoids and many amoebozoans, and unicellular organisms with sexual reproduction, colonial or not, like the volvocine algae Pandorina and Chlamydomonas, are "immortal" at some extent, dying only due to external hazards, like being eaten or meeting with a fatal accident. In multicellular organisms and also in multinucleate ciliates[136] with a Weismannist development, that is, with a division of labor between mortal somatic (body) cells and "immortal" germ (reproductive) cells, death becomes an essential part of life, at least for the somatic line.[137]

The Volvox algae are among the simplest organisms to exhibit that division of labor between two completely different cell types, and as a consequence, include the death of somatic line as a regular, genetically regulated part of its life history.[137][138]

Grief in animals

Animals have sometimes shown grief for their partners or "friends." When two chimpanzees form a bond together, sexual or not, and one of them dies, the surviving chimpanzee will show signs of grief, ripping out their hair in anger and starting to cry; if the body is removed, they will resist, they will eventually go quiet when the body is gone, but upon seeing the body again, the chimp will return to a violent state.[139]

Furthermore, anthropologist Barbara J. King has suggested that one way to evaluate the expression of grief in animals is to look for altered behaviors such as social withdrawal, disrupted eating or sleeping, expression of affect, or increased stress reactions in response to the death of a family member, mate, or friend.[140] These criteria do not assume the ability to anticipate death, understand its finality, or experience emotions equivalent to those of humans, but at the same time do not rule out the possibility of those abilities existing in some animals or that different kinds of emotional experiences might constitute grief.[141] Based on these criteria, King gives examples of observed potential mourning behaviors in animals such as cetaceans, apes and monkeys, elephants, domesticated animals (including dogs, cats, rabbits, horses, and farmed animals), giraffes, peccaries, donkeys, prairie voles, and some species of birds.[140][142]

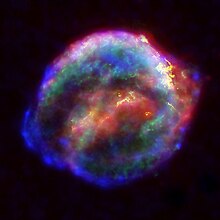

Death of abiotic factors

Some non-living things can be considered dead. For example, a volcano, batteries, electrical components, and stars are all nonliving things that can "die," whether from destruction or cessation of function.

A volcano, a break in the earth's crust that allows lava, ash, and gases to escape, has three states that it may be in, active, dormant, and extinct. An active volcano has recently or is currently erupting; in a dormant volcano, it has not erupted for a significant amount of time, but it may erupt again; in an extinct volcano, it may be cut off from the supply of its lava and will never be expected to erupt again, so the volcano can be considered to be dead.[citation needed]

A battery can be considered dead after the charge is fully used up. Electrical components are similar in this fashion, in the case that it may not be able to be used again, such as after a spill of water on the components,[143] the component can be considered dead.

Stars also have a life-span and, therefore, can die. After it starts to run out of fuel, it starts to expand, this can be analogous to the star aging. After it exhausts all fuel, it may explode in a supernova,[144] collapse into a black hole, or turn into a neutron star.[145]

Religious views

Buddhism

In Buddhist doctrine and practice, death plays an important role. Awareness of death motivated Prince Siddhartha to strive to find the "deathless" and finally attain enlightenment. In Buddhist doctrine, death functions as a reminder of the value of having been born as a human being. Rebirth as a human being is considered the only state in which one can attain enlightenment. Therefore, death helps remind oneself that one should not take life for granted. The belief in rebirth among Buddhists does not necessarily remove death anxiety since all existence in the cycle of rebirth is considered filled with suffering, and being reborn many times does not necessarily mean that one progresses.[146]

Death is part of several key Buddhist tenets, such as the Four Noble Truths and dependent origination.[146]

Christianity

While there are different sects of Christianity with different branches of belief, the overarching ideology on death grows from the knowledge of the afterlife. After death, the individual will undergo a separation from mortality to immortality; their soul leaves the body, entering a realm of spirits. Following this separation of body and spirit (death), resurrection will occur.[147] Representing the same transformation Jesus Christ embodied after his body was placed in the tomb for three days, each person's body will be resurrected, reuniting the spirit and body in a perfect form. This process allows the individual's soul to withstand death and transform into life after death.[148]

Hinduism

In Hindu texts, death is described as the individual eternal spiritual jiva-atma (soul or conscious self) exiting the current temporary material body. The soul exits this body when the body can no longer sustain the conscious self (life), which may be due to mental or physical reasons or, more accurately, the inability to act on one's kama (material desires).[149] During conception, the soul enters a compatible new body based on the remaining merits and demerits of one's karma (good/bad material activities based on dharma) and the state of one's mind (impressions or last thoughts) at the time of death.[150]

Usually, the process of reincarnation makes one forget all memories of one's previous life. Because nothing really dies and the temporary material body is always changing, both in this life and the next, death means forgetfulness of one's previous experiences.[151]

Islam

The Islamic view is that death is the separation of the soul from the body as well as the beginning of the afterlife.[152] The afterlife, or akhirah, is one of the six main beliefs in Islam. Rather than seeing death as the end of life, Muslims consider death as a continuation of life in another form.[153] In Islam, life on earth right now is a short, temporary life and a testing period for every soul. True life begins with the Day of Judgement when all people will be divided into two groups. The righteous believers will be welcomed to janna (heaven), and the disbelievers and evildoers will be punished in jahannam (hellfire).[154]

Muslims believe death to be wholly natural and predetermined by God. Only God knows the exact time of a person's death.[155] The Quran emphasizes that death is inevitable, no matter how much people try to escape death, it will reach everyone. (Q50:16) Life on earth is the one and only chance for people to prepare themselves for the life to come and choose to either believe or not believe in God, and death is the end of that learning opportunity.[156]

Judaism

There are a variety of beliefs about the afterlife within Judaism, but none of them contradict the preference for life over death. This is partially because death puts a cessation to the possibility of fulfilling any commandments.[157]

Language

The word "death" comes from Old English dēaþ, which in turn comes from Proto-Germanic *dauþuz (reconstructed by etymological analysis). This comes from the Proto-Indo-European stem *dheu- meaning the "process, act, condition of dying."[158]

The concept and symptoms of death, and varying degrees of delicacy used in discussion in public forums, have generated numerous scientific, legal, and socially acceptable terms or euphemisms. When a person has died, it is also said they have "passed away", "passed on", "expired", or "gone", among other socially accepted, religiously specific, slang, and irreverent terms.

As a formal reference to a dead person, it has become common practice to use the participle form of "decease", as in "the deceased"; another noun form is "decedent".

Bereft of life, the dead person is a "corpse", "cadaver", "body", "set of remains", or when all flesh is gone, a "skeleton". The terms "carrion" and "carcass" are also used, usually for dead non-human animals. The ashes left after a cremation are lately called "cremains".

See also

References

- ^ "death". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Hayman J, Oxenham M (2016). Human body decomposition. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-803713-3. OCLC 945734521.

- ^ Masamoto Y, Piraino S, Miglietta MP (December 2019). "Transcriptome Characterization of Reverse Development in Turritopsis dohrnii (Hydrozoa, Cnidaria)". G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 9 (12): 4127–4138. doi:10.1534/g3.119.400487. PMC 6893190. PMID 31619459.

- ^ Proskuryakov SY, Konoplyannikov AG, Gabai VL (February 2003). "Necrosis: a specific form of programmed cell death?". Experimental Cell Research. 283 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00027-7. PMID 12565815.

- ^ Louten J (2016). Essential Human Virology. Elsevier Science. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-12-801171-3.

- ^ Li R, Cheng X, Yang Y, C Schwebel D, Ning P, Li L, Rao Z, Cheng P, Zhao M, Hu G (2023). "Global Deaths Associated with Population Aging — 1990–2019". China CDC Weekly. 5 (51): 1150–1154. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2023.216. PMC 10750162. PMID 38152634.

- ^ Richtie H, Spooner F, Roser M (February 2018). "Causes of death". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 20 May 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Routley N (25 March 2022). "How Many Humans Have Ever Lived?". Visual Capitalist. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ a b Stambler I (1 October 2017). "Recognizing Degenerative Aging as a Treatable Medical Condition: Methodology and Policy". Aging and Disease. 8 (5): 583–589. doi:10.14336/AD.2017.0130. PMC 5614323. PMID 28966803.

- ^ a b Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VL (16 April 2010). "Extending Healthy Life Span—From Yeast to Humans". Science. 328 (5976): 321–326. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..321F. doi:10.1126/science.1172539. PMC 3607354. PMID 20395504.

- ^ a b United States. President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1981). Defining Death: A Report on the Medical, Legal and Ethical Issues in the Determination of Death · Part 34. The Commission. p. 63. Archived from the original on 17 August 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ a b United States Department of the Army (1999). Leadership Education and Training (LET 1). United States Department of the Army. p. 188. Archived from the original on 17 August 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ a b Zaner RM (2011). Death: Beyond Whole-Brain Criteria (1st ed.). Springer. pp. 77, 125. ISBN 978-94-010-7720-0.

- ^ "brain death". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ DeGrazia D (2021). "The Definition of Death". In Zalta EN (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Parent B, Turi A (December 2020). "Death's Troubled Relationship With the Law". AMA Journal of Ethics. 22 (12): E1055–1061. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2020.1055. PMID 33419507.

- ^ a b Newcomb T (17 October 2019). "7 Unique Burial Rituals Across the World". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Samir Hossain Mohammad, Gilbert Peter (2010). "Concepts of Death: A key to our adjustment". Illness, Crisis and Loss. 18 (1).

- ^ Veatch RM, Ross LF (2016). Defining Death: The Case for Choice. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-62616-356-0.

- ^ Henig, Robin Marantz (April 2016). "Crossing Over: How Science Is Redefining Life and Death". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 November 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ Animal Ethics (2023). "What beings are not conscious". Animal Ethics. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Antony M (February 2001). "Is 'consciousness' ambiguous?". Journal of Consciousness Studies. 8 (2): 19–44.

- ^ Metcalf P, Huntington R (1991). Celebrations of Death: The Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual. New York: Cambridge Press.[page needed]

- ^ a b DeGrazia D (2017). "The Definition of Death". In Zalta EN (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d Bernat JL (2018). "Conceptual Issues in DCDD Donor Death Determination". Hastings Center Report. 48 (S4): S26–S28. doi:10.1002/hast.948. PMID 30584853.

- ^ Belkin GS (2014). Death Before Dying: History, Medicine, and Brain Death. Oxford University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-19-989817-6.

- ^ New York State Department of Health (2011). "Guidelines for Determining Brain Death". New York State. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ National Health Service of the UK (8 September 2022). "Overview: Brain death". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 12 November 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Nitkin K (11 September 2017). "The Challenges of Defining and Diagnosing Brain Death". Johns Hopkins Medicine. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Chernecky CC, Berger BJ (2013). Laboratory Tests and Diagnostic Procedures (6th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4557-0694-5.

- ^ Miller F (October 2009). "Death and organ donation: back to the future". Journal of Medical Ethics. 35 (10): 616–620. doi:10.1136/jme.2009.030627. PMID 19793942.

- ^ Magnus DC, Wilfond BS, Caplan AL (6 March 2014). "Accepting Brain Death". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (10): 891–894. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1400930. PMID 24499177.

- ^ Nicol AU, Morton AJ (11 June 2020). "Characteristic patterns of EEG oscillations in sheep (Ovis aries) induced by ketamine may explain the psychotropic effects seen in humans". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 9440. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.9440N. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-66023-8. PMC 7289807. PMID 32528071.

- ^ New York Department of Health (5 December 2011). "Guidelines for Determining Brain Death". New York State. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, American Bar Association, American Medical Association (1981). Uniform Determination of Death Act (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Lewis A, Cahn-Fuller K, Caplan A (2017). "Shouldn't Dead Be Dead?: The Search for a Uniform Definition of Death". Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 45 (1): 112–128. doi:10.1177/1073110517703105. PMID 28661278.

- ^ Sarbey B (1 December 2016). "Definitions of death: brain death and what matters in a person". Journal of Law and the Biosciences. 3 (3): 743–752. doi:10.1093/jlb/lsw054. PMC 5570697. PMID 28852554.

- ^ a b c Bernat JL (March 2013). "Controversies in defining and determining death in critical care". Nature Reviews Neurology. 9 (3): 164–173. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.12. PMID 23419370.

- ^ Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (June 2021). "The physical process of dying". Health Direct. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b Dolinak D, Matshes E, Lew EO (2005). Forensic Pathology: Principles and Practice. Elsevier Academic Press. p. 526. ISBN 978-0-08-047066-5.

- ^ Medical certification of cause of death : instructions for physicians on use of international form of medical certificate of cause of death. World Health Organization. 1979. hdl:10665/40557. ISBN 978-92-4-156062-7.[page needed]

- ^ Bondeson 2001, p. 77

- ^ Bondeson 2001, pp. 56, 71.

- ^ Bondeson 2001, p. 239

- ^ a b Limmer, Dan, O'Keefe, Michael F., Bergeron, J. David, Grant, Harvey, Murray, Bob, Dickinson, Ed (21 December 2006). Brady Emergency Care AHA (10th Updated ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-159390-9.

- ^ a b Merkle R. "Information-Theoretic Death". merkle.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

A person is dead according to the information-theoretic criterion if the structures that encode memory and personality have been so disrupted that it is no longer possible in principle to recover them. If inference of the state of memory and personality are feasible in principle, and therefore restoration to an appropriate functional state is likewise feasible in principle, then the person is not dead.

- ^ a b c d e f de Grey AD (21 January 2007). "Life Span Extension Research and Public Debate: Societal Considerations". Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology. 1 (1). doi:10.2202/1941-6008.1011.

roughly 150,000 deaths that occur each day across the globe

- ^ "Tuberculosis Fact sheet N°104 – Global and regional incidence". WHO. March 2006. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ^ Chris Thomas, Global Health/Health Infectious Diseases and Nutrition (2 June 2009). "USAID's Malaria Programs". Usaid.gov. Archived from the original on 26 January 2004. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ "Aids could kill 90 million Africans, says UN". The Guardian. London. 4 March 2005. Archived from the original on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Leonard T (4 June 2006). "AIDS Toll May Reach 100 Million in Africa". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ Jean Ziegler, L'Empire de la honte, Fayard, 2007 ISBN 978-2-253-12115-2 p. 130.[clarification needed]

- ^ a b "WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008" (PDF). WHO. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ Olshansky SJ, Perry D, Miller RA, Butler RN (March 2006). "In pursuit of the longevity dividend: what should we be doing to prepare for the unprecedented aging of humanity?". The Scientist. 20 (3): 28–37. Gale A143579030.

- ^ Selye H (31 August 1938). "Experimental Evidence Supporting the Conception of 'Adaptation Energy'". American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content. 123 (3): 758–765. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1938.123.3.758.

- ^ Goldstone B (1952). "The general practitioner and the general adaptation syndrome". South African Medical Journal. 26 (6): 106–109. hdl:10520/AJA20785135_26742. PMID 14913266.

- ^ Gorban AN, Tyukina TA, Smirnova EV, Pokidysheva LI (September 2016). "Evolution of adaptation mechanisms: Adaptation energy, stress, and oscillating death". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 405: 127–139. arXiv:1512.03949. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.12.017. PMID 26801872.

- ^ Reinberg S (20 September 2012). "Suicide now kills more Americans than car crashes: study". Medical Express. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Mufson S (22 February 1995). "RIGHTS GROUP WARNS CHINA ON DAM PROJECT". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Liang G, Deng L (29 April 2013). "Solving a Mystery of 400 Years-An Explanation to the "explosion" in Downtown Beijing in the Year of 1626". AllBestEssays. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Humphrey JH (1986). Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. University of California Press. pp. 80, 102, 126–129. ISBN 978-0-520-04921-5.

- ^ Sovacool BK (May 2008). "The costs of failure: A preliminary assessment of major energy accidents, 1907–2007". Energy Policy. 36 (5): 1802–1820. Bibcode:2008EnPol..36.1802S. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.01.040.

- ^ Sovacool BK (August 2010). "A Critical Evaluation of Nuclear Power and Renewable Electricity in Asia". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 40 (3): 369–400. doi:10.1080/00472331003798350.

- ^ "The World's Worst Natural Disasters: Calamities of the 20th and 21st centuries". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 30 August 2010. Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Means T, Pappas S (3 March 2022). "10 of the deadliest natural disasters in history". LiveScience. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ ""The 16 deadliest storms of the last century"". Business Insider India. 13 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Dohner JV (2017). The encyclopedia of animal predators: learn about each predator's traits and behaviors: identify the tracks and signs of more than 50 predators: protect your livestock, poultry, and pets. North Adams, Massachusetts: Storey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61212-705-7. OCLC 970604110.[page needed]

- ^ a b Johns Hopkins Medical (19 November 2019). "Autopsy". Johns Hopkins Medical. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Maryland Department of Health. "Forensic Autopsy". Maryland Department of Health. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Madea B, Rothschild M (1 June 2010). "The Post Mortem External Examination". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International (in German). 103 (33): 575–586, quiz 587–588. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2010.0575. PMC 2936051. PMID 20830284. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Duke University School of Medicine. "Autopsy Pathology". Duke Department of Pathology. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Fadden M, Peaslee J (19 March 2019). "What's a Necropsy? The Science Behind this Valuable Diagnostic Tool". Cornell University. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Goldenberg R, Kirby R, Culhane J (August 2004). "Stillbirth: a review". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 16 (2): 79–94. doi:10.1080/jmf.16.2.79.94.

- ^ García-Enguídanos A, Calle M, Valero J, Luna S, Domínguez-Rojas V (10 May 2002). "Risk factors in miscarriage: a review". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 102 (2): 111–119. doi:10.1016/S0301-2115(01)00613-3. PMID 11950476.

- ^ Lawrence B, Finer LF, Frohwirth L, Dauphinee A, Singh S, Moore AM (September 2005). "Reasons U.S. Women Have Abortions: Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 37 (3): 110–118. doi:10.1111/j.1931-2393.2005.tb00045.x. PMID 16150658.

- ^ Attia (21 November 2019). "What are the different types of abortion?". Planned Parenthood. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "The top five causes of premature death". familyserviceshub.havering.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ Hayflick L, Moody HR (2003). Has Anyone Ever Died of Old Age?. International Longevity Center–USA. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ "Turritopsis nutricula (Immortal jellyfish)". Jellyfishfacts.net. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Crippen D. "Brain Failure and Brain Death". Scientific American Surgery, Critical Care, April 2005. Archived from the original on 24 June 2006. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ Burkle CM, Sharp RR, Wijdicks EF (14 October 2014). "Why brain death is considered death and why there should be no confusion". Neurology. 83 (16): 1464–1469. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000883. PMC 4206160. PMID 25217058.

- ^ Blagosklonny MV (1 December 2021). "No limit to maximal lifespan in humans: how to beat a 122-year-old record". Oncoscience. 2021 (8): 110–119. doi:10.18632/oncoscience.547. PMC 8636159. PMID 34869788.

- ^ "Living to 120 and Beyond: Americans' Views on Aging, Medical Advances and Radical Life Extension". Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 6 August 2013. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ Moshakis A (23 June 2019). "How to live forever: meet the extreme life-extensionists". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ McKie R (13 July 2002). "Cold facts about cryonics". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

Cryonics, which began in the Fifties, is the freezing – usually in liquid nitrogen – of human beings who have been legally declared dead. The aim of this process is to keep such individuals in a state of refrigerated limbo so that it may become possible in the future to resuscitate them, cure them of the condition that killed them, and then restore them to functioning life in an era when medical science has triumphed over the activities of the Banana Reaper

- ^ "What is Cryonics?". Alcor Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

Cryonics is an effort to save lives by using temperatures so cold that a person beyond help by today's medicine might be preserved for decades or centuries until a future medical technology can restore that person to full health.

- ^ Whetstine L, Streat S, Darwin M, Crippen D (2005). "Pro/con ethics debate: When is dead really dead?". Critical Care. 9 (6): 538–42. doi:10.1186/cc3894. PMC 1414041. PMID 16356234.

- ^ Best B (2008). "Scientific justification of cryonics practice". Rejuvenation Research. 11 (2): 493–503. doi:10.1089/rej.2008.0661. PMC 4733321. PMID 18321197.

- ^ Lovgren S (18 March 2005). "Corpses Frozen for Future Rebirth by Arizona Company". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

Many cryobiologists, however, scoff at the idea...

- ^ Paasonen A (1974). Marsalkan tiedustelupäällikkönä ja hallituksen asiamiehenä [Marshall's chief of intelligence and Government's official] (in Finnish). Weilin & Göös. ISBN 978-951-35-1173-9.[page needed]

- ^ Hokkanen K. "Kallio, Kyösti (1873–1940) President of Finland". Biografiakeskus, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Ariès P (1974). Western attitudes toward death: from the Middle Ages to the present. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-0-8018-1762-5.

- ^ a b c Nuland SB (1994). How we die: Reflections on life's final chapter. New York: A.A. Knopf. pp. 254–255. ISBN 978-0-679-41461-2.

- ^ Ahmad S, O'Mahony M (December 2005). "Where older people die: a retrospective population-based study". QJM. 98 (12): 865–870. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hci138. PMID 16299059.

- ^ Cassel CK, Demel B (September 2001). "Remembering death: public policy in the USA". J R Soc Med. 94 (9): 433–436. doi:10.1177/014107680109400905. PMC 1282180. PMID 11535743.

- ^ Ariès P (1981). "Invisible Death". The Wilson Quarterly. 5 (1): 105–115. JSTOR 40256048. PMID 11624731.

- ^ Solomon S, Piven JS (2014). "Death and Dying". Oxford Bibliographies Online. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0144.

- ^ Jong J, Ross R, Philip T, Chang SH, Simons N, Halberstadt J (2 January 2018). "The religious correlates of death anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Religion, Brain & Behavior. 8 (1): 4–20. doi:10.1080/2153599X.2016.1238844. See also "Study into who is least afraid of death" (Press release). University of Oxford. 24 March 2017.

- ^ Harmon-Jones E, Simon L, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S, McGregor H (1997). "Terror management theory and self-esteem: Evidence that increased self-esteem reduced mortality salience effects". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 72 (1): 24–36. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.24. PMID 9008372.

- ^ Pyszczynski TA (2003). In the wake of 9/11: the psychology of terror. Jeff Greenberg, Sheldon Solomon. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ISBN 1-55798-954-0. OCLC 49719188.[page needed]

- ^ a b Strawson G (2018). Things that Bother Me: Death, Freedom, the Self, Etc. New York Review of Books. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-1-68137-220-4. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Strawson G (2017). "'We live beyond…any tale that we happen to enact'". The Subject of Experience. pp. 106–122. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198777885.003.0006. ISBN 978-0-19-877788-5.

- ^ Heath PR, Klimo J (2010). Handbook to the Afterlife. North Atlantic Books. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-55643-869-1. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ Williams V (2016). Celebrating Life Customs Around the World: From Baby Showers to Funerals [3 Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3659-6.

- ^ Mullin 1998[page needed]

- ^ a b Brenner E (18 January 2014). "Human body preservation – old and new techniques". Journal of Anatomy. 224 (3): 316–344. doi:10.1111/joa.12160. PMC 3931544. PMID 24438435.

- ^ Lutz D (2011). "The Dead Still Among Us: Victorian Secular Relics, Hair Jewelry, and Death Culture". Victorian Literature and Culture. 39 (1): 127–142. doi:10.1017/S1060150310000306. JSTOR 41307854.

- ^ Dimond B (2008). Legal Aspects of Death (6th ed.). Quay Books. ISBN 978-1-85642-333-5.

- ^ "Shot at Dawn, campaign for pardons for British and Commonwealth soldiers executed in World War I". Shot at Dawn Pardons Campaign. Archived from the original on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 20 July 2006.

- ^ a b United States Department of the Army (1982). Military Judges' Benchbook: Part 1. United States Department of the Army. Archived from the original on 17 August 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Hassankhani H, Haririan H, Porter JE, Heaston S (July 2018). "Cultural aspects of death notification following cardiopulmonary resuscitation". Journal of Advanced Nursing. 74 (7): 1564–1572. doi:10.1111/jan.13558. PMID 29495080.

- ^ Carducci BJ (2009). The Psychology of Personality: Viewpoints, Research, and Applications (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3635-8.[page needed]

- ^ Math SB, Chaturvedi SK (December 2012). "Euthanasia: Right to life vs right to die". Indian Journal of Medical Research. 136 (6): 899–902. PMC 3612319. PMID 23391785.

- ^ Masataka K (March 2005). "The Showa Era (1926–1989)". Daedalus. 119 (3): 24–27. doi:10.1162/daed.2005.134.issue-2. JSTOR 20025315.

- ^ Chesnut RA (2012). "Introduction: Blue CandleInsight and Concentration". Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint. pp. 3–26. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199764662.003.0000. ISBN 978-0-19-976466-2.

- ^ McKenna A (17 August 2016). "Where Does the Concept of a "Grim Reaper" Come From?". Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Nations MK, Amaral ML (September 1999). "Flesh, Blood, Souls, and Households: Cultural Validity in Mortality Inquiry". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 5 (3): 204–220. doi:10.1525/maq.1991.5.3.02a00020.

- ^ Denise Cush, Catherine A. Robinson, Michael York, eds. (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1267-0. OCLC 62133001.

- ^ a b Green JW (2008). Beyond the good death: the anthropology of modern dying. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0207-6. OCLC 835765644.

- ^ Dundes A, ed. (1984). Sacred narrative, readings in the theory of myth. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05156-4. OCLC 9944508.

- ^ Patton LL, Doniger W, eds. (1996). Myth and method. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-8139-1656-9. OCLC 34516050.

- ^ Boas F (October 1917). "The Origin of Death". The Journal of American Folklore. 30 (118): 486–491. doi:10.2307/534498. JSTOR 534498.

- ^ Lang A (2007). Modern mythology. Middlesex: Echo Library. ISBN 978-1-4068-1672-3. OCLC 269027849.

- ^ Greyson B, James D, Holden JM (2009). The Handbook of Near-Death Experiences: Thirty Years of Investigation. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35865-4.

- ^ Falkowski PG (2001). "Biogeochemical Cycles". Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. pp. 437–453. doi:10.1016/b0-12-226865-2/00032-8. ISBN 978-0-12-226865-6.

- ^ Wetzel R (2001). Limnology: Lake and River Ecosystems (3rd ed.). Elsevierda. p. 700. ISBN 978-0-12-744760-5.

- ^ Lindsey-Robbins J, Vázquez-Ortega A, McCluney K, Pelini S (13 December 2019). "Effects of Detritivores on Nutrient Dynamics and Corn Biomass in Mesocosms". Insects. 10 (12): 453. doi:10.3390/insects10120453. PMC 6955738. PMID 31847249.

- ^ Rousk J, Bengston P (14 March 2014). "Microbial regulation of global biogeochemical cycles". Frontiers in Microbiology. 5: 103. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00103. PMC 3954078. PMID 24672519.

- ^ George M (2018). Carboniferous Giants and Mass Extinction: The Late Paleozoic Ice Age World. Columbia University Press. pp. 98–102. ISBN 978-0-231-18097-9.

- ^ Gregory TR (June 2009). "Understanding Natural Selection: Essential Concepts and Common Misconceptions". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 2 (2): 156–175. doi:10.1007/s12052-009-0128-1.

- ^ Haldane JB (December 1957). "The cost of natural selection". Journal of Genetics. 55 (3): 511–524. doi:10.1007/BF02984069.

- ^ Case TJ, Gilpin ME (1 August 1974). "Interference Competition and Niche Theory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (8): 3073–3077. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.3073C. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.8.3073. PMC 388623. PMID 4528606.

- ^ Diamond JM (1999). "Up to the Starting Line". Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (illustrated, reprint ed.). W.W. Norton. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-393-31755-8.

- ^ Purvis A, Jones KE, Mace GM (10 November 2000). "Extinction". BioEssays. 22 (12): 1123–1133. doi:10.1002/1521-1878(200012)22:12<1123::AID-BIES10>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 11084628.

- ^ National Institute on Aging (2020). "The National Institute on Aging: Strategic Directions for Research, 2020–2025". National Institute on Aging. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Beukeboom LW, Perrin N (2014). "The diversity of sexual cycles". The Evolution of Sex Determination. pp. 18–36. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199657148.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-965714-8.

- ^ a b Gilbert S (2003). Developmental biology (7th ed.). Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-87893-258-0.

- ^ Hallmann A (June 2011). "Evolution of reproductive development in the volvocine algae". Sexual Plant Reproduction. 24 (2): 97–112. doi:10.1007/s00497-010-0158-4. PMC 3098969. PMID 21174128.

- ^ Brown AE (March 1879). "Grief in the Chimpanzee". The American Naturalist. 13 (3): 173–175. doi:10.1086/272298. JSTOR 2448772.

- ^ a b King BJ (2014). How Animals Grieve. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-15520-3.[page needed]

- ^ King BJ (2016). "Animal mourning: Précis of How animals grieve (King 2013)". Animal Sentience. 1 (4). doi:10.51291/2377-7478.1010.

- ^ King BJ (2019). "The ORCA'S SORROW". Scientific American. 320 (3): 30–35. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0319-30. JSTOR 27265108. PMID 39010370.

- ^ Baylakoğlu İ, Fortier A, Kyeong S, Ambat R, Conseil-Gudla H, Azarian MH, Pecht MG (28 October 2021). "The detrimental effects of water on electronic devices". E-Prime – Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy. 1 (10): 1016. doi:10.1016/j.prime.2021.100016.

- ^ Croswell K (21 January 2020). "A massive star dies without a bang, revealing the sensitive nature of supernovae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (3): 1240–1242. doi:10.1073/pnas.1920319116. PMC 6983415. PMID 31964780.

- ^ Heger A, Fryer CL, Woosley SE, Langer N, Hartmann DH (July 2003). "How Massive Single Stars End Their Life". The Astrophysical Journal. 591 (1): 288–300. arXiv:astro-ph/0212469. Bibcode:2003ApJ...591..288H. doi:10.1086/375341.

- ^ a b Blum ML (2004). "Death" (PDF). In Buswell RE (ed.). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Vol. 1. New York: Macmillan Reference, Thomson Gale. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-02-865720-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Second Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians. Alfred Plummer". The Biblical World. 46 (3): 192. September 1915. doi:10.1086/475371.

- ^ "Resurrection – Resurrection of Christ". Sacramentum Mundi Online. doi:10.1163/2468-483x_smuo_com_003831.

- ^ The Hindu Kama Shastra Society (1925). The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana. University of Toronto Archives. pp. 8–11, 172.

- ^ Yadav R (2018). "Rebirth (Hinduism)". Hinduism and Tribal Religions. Encyclopedia of Indian Religions. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-1036-5_316-1. ISBN 978-94-024-1036-5.

- ^ Sharma A (March 1996). "THE ISSUE OF MEMORY AS A PRAMĀṆA AND ITS IMPLICATION FOR THE CONFIRMATION OF REINCARNATION IN HINDUISM". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 24 (1). Springer: 21–36. doi:10.1007/BF00219274. JSTOR 23447913.

- ^ Smith JI, Haddad YY (12 December 2002). "From Death to Resurrection: Classical Islam". The Islamic Understanding of Death and Resurrection. Oxford University PressNew York. pp. 31–62. doi:10.1093/0195156498.003.0002. ISBN 0-19-515649-8.

- ^ Puchalski CM, O'Donnell E (July 2005). "Religious and spiritual beliefs in end of life care: how major religions view death and dying". Techniques in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Management. 9 (3): 114–121. doi:10.1053/j.trap.2005.06.003.

- ^ Oliver Leaman, ed. (2006). The Qurʼan: an encyclopedia. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-17644-8. OCLC 68963889.

- ^ Tayeb MA, Al-Zamel E, Fareed MM, Abouellail HA (May 2010). "A 'good death': perspectives of Muslim patients and health care providers". Annals of Saudi Medicine. 30 (3): 215–221. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.62836. PMC 2886872. PMID 20427938.

- ^ Campo JE (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1. OCLC 191882169.

- ^ Raphael SP (May 2021). Jewish Views of the Afterlife (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "Death". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

Bibliography

- Bondeson J (2001). Buried Alive: the Terrifying History of our Most Primal Fear. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04906-0.

- Mullin GH (2008) [1998]. Living in the Face of Death: The Tibetan Tradition. Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 978-1-55939-310-2.

Further reading

- Cochem Mo (1899). . The four last things: death, judgment, hell, heaven. Benziger Brothers.

- Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. (1856). . St. Vincent's Manual. John Murphy & Co.

- Liguori, Alphonsus (1868). . Rivingtons.

- Marques SM (2015). Now and At the Hour of Our Death. Translated by Sanches J. And Other Stories. ISBN 978-1-908276-62-9.

- Massillon JB (1879). . Sermons by John-Baptist Massillon. Thomas Tegg & Sons.

- Rosenberg D (17 August 2014). "How One Photographer Overcame His Fear of Death by Photographing It (Walter Schels' Life Before Death)". Slate.

- Sachs, Jessica Snyder (2001). Corpse: Nature, Forensics, and the Struggle to Pinpoint Time of Death (270 pages). Perseus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7382-0336-2.

- Warraich H (2017). Modern Death: How Medicine Changed the End of Life. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-10458-8.

External links

- "Death" Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 898–900.

- Best, Ben. "Causes of Death". BenBest.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Death" (video; 10:18) by Timothy Ferris, producer of the Voyager Golden Record for NASA. 2021