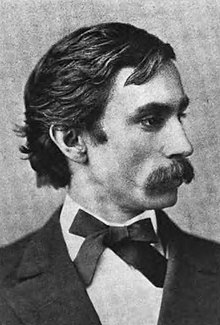

Richard Watson Gilder

Richard Watson Gilder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 8, 1844 |

| Died | November 19, 1909 (aged 65) |

| Occupation(s) | poet, editor |

| Spouse | Helena de Kay Gilder |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Richard Watson Gilder (February 8, 1844 – November 19, 1909) was an American poet and editor.

Life and career

[edit]

Gilder was born on February 8, 1844[1] at Bordentown, New Jersey. He was the son of Jane (Nutt) Gilder and the Rev. William Henry Gilder, and educated at his father's seminary in Flushing, Queens. There he learned to set type and published the St. Thomas Register.[2] Gilder later studied law at Philadelphia.

During the American Civil War, he enlisted in the state's Emergency Volunteer Militia as a private in Landis' Philadelphia Battery at the time of the Robert E. Lee's 1863 invasion of Pennsylvania. After the Confederates were defeated in the Battle of Gettysburg, Gilder and his unit were mustered out in August. The death of his father, while serving as chaplain of the Fortieth New York Volunteers, obliged him to give up the study of the law.[2]

A little later, he became a reporter on the Newark (New Jersey) Advertiser, of which he was later editor. With Newton Crane, he founded the Newark Register. In 1870, he became editor of Hours at Home, a monthly magazine published by Scribner's. It merged with Scribner's Monthly, which was edited by J. G. Holland. Gilder became managing editor. When Holland died in 1881, Gilder became editor. In November 1881, the monthly was renamed as The Century Magazine, and Gilder remained its editor until his death.[2] Gilder's assistant editor at Century was Sophia Bledsoe Herrick.[3] Under Gilder's editorship, The Century became one of the most esteemed periodicals in the country and Gilder himself became influential enough that his biographer Herbert Smith referred to the 1880s as "the Gilder Age". He published the works of William Dean Howells, Henry James, Mark Twain, and Walt Whitman[4]

Gilder took an active interest in all public affairs, especially those which tend towards reform and good government, and was a member of many New York clubs. He was one of the founders of the Society of American Architects, of the Authors' Club, and of the International Copyright League. He was a founder of the Anti-Spoils League and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was a close friend of George MacDonald, Scottish poet, author, and preacher. They collaborated in various ventures such as MacDonald's American lecture tour in the 1870s. Gilder received the degree of LL.D. from Dickinson College in 1883.[5]

As editor of Century Gilder editorialized against women's suffrage. He wrote that giving women the right to vote would destroy the "home woman" who was an anchor of family stability in a changing world. He regarded women as guardians of the nation's morality, and excluded anything from the magazine that would "corrupt" women.[6]

Gilder was a member of the Simplified Spelling Board. He was a leader in the organization of the Citizens' Union, a founder and the first president of the Kindergarten Association, and of the New York Association for the Blind. Gilder was chairman of the first Tenement House Commission in New York City. During his service on the commission, he arranged to be called whenever there was a fire in a tenement house, and at all hours of the night he risked his health and his life itself to see the perils besetting the dwellers of the tenements, in order to make wise recommendations as to legislation that would minimize these perils.[2]

Family

[edit]

On June 3, 1874, Gilder married a daughter of Commodore George Coleman De Kay, Helena de Kay Gilder (1846–1916).[2] Gilder met his wife, Helena de Kay Gilder, in May 1872 while she was visiting the offices of Scribner's Monthly, where Richard Watson Gilder was at the time working as an editor. About a year and a half later, in February 1874, Helena and Richard became engaged. Richard Watson Gilder and Helena de Kay Gilder are known to have kept a lengthy correspondence with each other via letter over the course of their marriage. Helena de Kay Gilder is also known to be the subject of love poems written by Richard Watson Gilder, and they partnered together on some of his books, with her working as the illustrator, such as in Two Worlds and Other Poems (1891). She was a talented painter and a founder of the Art Students League and Society of American Artists. She also modeled for, and was an unrequited love of, the painter Winslow Homer.[7] Gilder and de Kay were the models for the characters Thomas and Augusta Hudson in Wallace Stegner's Pulitzer-prize winning novel, Angle of Repose. Their son, Rodman de Kay Gilder (1877–1953), became an author and married Louise Comfort Tiffany, a daughter of Louis Comfort Tiffany. Their daughter, Rosamond Gilder, was a notable theater critic.[8] A celebrated plaster sculpture of the family by Augustus Saint-Gaudens is owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[9] The Berkshires summer home of Helena de Kay and Richard Watson Gilder is being turned into a museum.[10]

Gilder's siblings were William Henry Gilder, an explorer; Jeannette Leonard Gilder, a journalist; and Joseph Benson Gilder, an editor. His great-grandson George Gilder is a renowned author and was a speechwriter for Richard Nixon.

Frank Weitenkampf recounts the following anecdote of Gilder and Alexander Wilson Drake:[11]

- Drake and some friends, late one Christmas Eve (or was it Thanksgiving?), wandering down the Bowery, came across a turkey raffle. They took chances, and won the bird, a large, live specimen. What to do with it? One of the party had a happy idea. Off they marched to Gilder's house, rang up the butler, and persuaded him to let them tie the bird to a large chair in the front room. Drake continued the story to the effect that Gilder early next morning was aroused by a terrific racket, rushed downstairs, and found the children hilariously dancing around the turkey, whose excited gobbling added to the din.

Death

[edit]Gilder died suddenly in New York City on Friday 19 November 1909 of a heart attack in the home of Schuyler van Rensselaer (at 9 West 10th St). [12] The cause of death is considered to be heart disease. He had been staying at the Rensselaer home as a guest for several days (since the previous Monday, 15 November 1909) with his wife (Helena) when he suddenly died. He had been ill two weeks prior to his death, while he had been giving a lecture, but the incident was not considered to be serious at the time. [13] Gilder is buried at the Bordentown Cemetery in Bordentown New Jersey.

Following his death, he was remembered by Theodore Roosevelt as:

- one of the truest, stanchest, and most delightful of friends, and one of the best of citizens. He combined to a singular degree sweetness and courage, idealism and wholesome common sense. It may be truthfully said that he was an ideal citizen for such democracy as ours. He was a man of letters; he was a lover of his kind who worked in a practical fashion for the betterment of social and economic conditions, and he took keen and effective interest in our public life. No worthier American citizen has lived during our time.[14]

Selected works

[edit]

- The New Day (1875)

- Lyrics and Other Poems (1885)

- The Celestial Passion (1887)

- Two Worlds and Other Poems (1891)

- Five Books of Song (1894)

- In Palestine, and Other Poems (1898)

- Poems and Inscriptions (1901)

- In the Heights (1905)

- A Book of Music (1906)

- Grover Cleveland: A Record of Friendship

Gilder's daughter, Rosamond Gilder, edited Letters of Richard Watson Gilder, published by Houghton Mifflin Company in 1916.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ The Magazine of Poetry and Literary Review, vol.1, pg.3

- ^ a b c d e

Homans, James E., ed. (1918). . The Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: The Press Association Compilers, Inc.

Homans, James E., ed. (1918). . The Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: The Press Association Compilers, Inc.

- ^ Hollis, C. Carroll (1979). "Sophia Bledsoe Herrick". In Flora, Joseph M. (ed.). Southern writers: a biographical dictionary. LSU Press. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-0-8071-0390-6. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Roberson, Susan L. "Richard Watson Gilder" in Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia (J. R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings, editors). New York: Routledge, 1998: 254. ISBN 0-8153-1876-6

- ^ Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ Marshall, Susan E. (1997). Splintered Sisterhood. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9780299154639.

- ^ "The Courtship of Winslow Homer," Magazine Antiques, Feb 2002. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ "Rosamund Gilder - Oxford Reference". www.oxfordreference.com. Retrieved Apr 28, 2019.

- ^ "Augustus Saint-Gaudens: Richard Watson Gilder, Helena de Kay Gilder, and Rodman de Kay Gilder | Work of Art | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Archived from the original on 2008-04-06.

- ^ "Four Brooks Farm". www.fourbrooksfarm.org. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Manhattan Kaleidoscope, Frank Weitenkampf, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1947, page 138.

- ^ "R.W. Gilder dies of heart disease". New York Times. 19 May 1909. p. 1. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Author and Book Info .com - The Companion to Online and Offline Literature

- ^ "ROOSEVELT PRAISES GILDER.; Declares Richard Watson Gilder Fellowships a Fitting Tribute". The New York Times. 1910-05-03. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-06-17.

- Bibliography

Cousin, John William (1910), "Gilder, Richard Watson", A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource

Cousin, John William (1910), "Gilder, Richard Watson", A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Van Rensselaer, Schuyler (March 3, 1922). "Richard Watson Gilder - Personal Memories". The Outlook. 130: 376–379. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Richard Watson Gilder at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Richard Watson Gilder at Wikiquote Works by or about Richard Watson Gilder at Wikisource

Works by or about Richard Watson Gilder at Wikisource- Works by or about Richard Watson Gilder at the Internet Archive

- Works by Richard Watson Gilder at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1844 births

- 1909 deaths

- Union army soldiers

- American male poets

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- American newspaper founders

- People from Bordentown, New Jersey

- Writers from Queens, New York

- People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War

- 19th-century American poets

- 19th-century American male writers

- Journalists from New York City

- American male non-fiction writers

- 19th-century American businesspeople