Nysa, Poland

Nysa | |

|---|---|

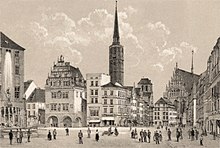

Main Square | |

| Nickname(s): Śląski Rzym (Silesian Rome) | |

| Coordinates: 50°28′17″N 17°20′2″E / 50.47139°N 17.33389°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Opole |

| County | Nysa |

| Gmina | Nysa |

| Established | 10th century |

| Town rights | 1223 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kordian Kolbiarz |

| Area | |

• Total | 27.5 km2 (10.6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 195 m (640 ft) |

| Population (2019-06-30[1]) | |

• Total | 43,849 |

| • Density | 1,600/km2 (4,100/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 48-300 |

| Area code | +48 77 |

| Car plates | ONY |

| Website | http://www.nysa.pl |

Nysa [ˈnɨsa] (German: Neisse or Neiße, Silesian: Nysa) is a city in southwestern Poland on the Eastern Neisse (Polish: Nysa Kłodzka) river, situated in the Opole Voivodeship. With 43,849 inhabitants (2019), it is the capital of Nysa County. It comprises the urban portion of the surrounding Gmina Nysa. Historically the city was part of Upper Silesia.

History

[edit]Medieval period

[edit]

Nysa, one of the oldest towns in Silesia, was probably founded in the 10th century. The name of the Nysa river, from which the town takes its name, was mentioned in 991, when the region formed part of the Duchy of Poland under Mieszko I of Poland. A Polish stronghold was built in Nysa in the 11th and 12th century due to the proximity of the border with the Czech Duchy. As a result of the fragmentation of Poland, it became part of the Duchy of Silesia, and from the 14th century it functioned as the capital of the Duchy of Nysa, administered by the Bishopric of Wrocław. In the 12th century the Gothic Basilica of St. James and St. Agnes was built (later rebuilt after the war devastations of the 13th and 14th centuries). Now designated a Historic Monument of Poland, it is the most distinctive and most valuable landmark of Nysa. Nysa was granted town rights around 1223 by bishop Lawrence, confirmed by Duke Bolesław II Rogatka of Legnica in 1250, and attracted Flemish and German settlers. In 1241 it was ravaged by the Mongols during the first Mongol invasion of Poland.[2] In 1245, it was granted staple right and two yearly fairs were established. In the early-14th century Nysa became an important trade- and craft-center of Poland, before it passed under the suzerainty of the Bohemian Crown in 1351,[2] under which it remained until 1742. It also became one of the leading cultural centers of Silesia.[3]

The town's fortifications, dating from 1350, served to defend against the Hussites in 1424. During the Hussite Wars, in 1428 it was the site of the Battle of Nysa, with Poles and Czechs fighting on both sides.[2] One of the prominent signs that Nysa was a significant center is the report in Nuremberg Chronicle, published in 1493, which mentions the city among the major urban centers of Central and Eastern Europe. In the description of the town population included in this chronicle we read "plebs rustica polonici ydeomatis ...". The Nysa coat of arms at the entrance of the Charles Bridge in Prague, which is displayed alongside the arms of the most prominent Bohemian cities, also indicates the importance of the town.

Modern period

[edit]In the 16th century it was a Polish printing center.[3]

During the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) Nysa was besieged three times. It was plundered by the Saxons and Swedes.[2] Polish prince (and later King) Władysław IV Vasa (r. 1632–1648) visited the town several times between 1619 and 1638. In 1624 the Kolegium Carolinum Neisse (today's I Liceum Ogólnokształcące), one of the most renowned schools of Silesia, was established as a Jesuit college.[3] Polish King Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki[4] and Polish prince James Louis Sobieski both attended this school.

During the First Silesian War (War of the Austrian Succession), in 1741, Nysa was besieged and captured by Prussians,[2] King Frederick II of Prussia laid the foundations of its modern fortifications. In 1758, during the Seven Years' War, it was besieged by the Austrians.[2] On 25 August 1769 it was the site of a meeting between Frederick II and Emperor Joseph II, co-regent in the Habsburg monarchy of Austria. Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, officer of the American Revolutionary War and French Revolution and co-author of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, was imprisoned in the town by the Prussians[5] in 1794.

During the Napoleonic Wars Neisse was taken by the French in 1807. It retained its mostly Catholic character within the predominantly Protestant province of Silesia in the Kingdom of Prussia. Because of its many churches from the Gothic and Baroque periods the town was nicknamed "the Silesian Rome". In 1816–1911, the town was the seat of the Neisse District, after which it became an independent city. During the Second Schleswig War of 1864, Prussians held Danish prisoners of war in the town,[6] who built a road named Aleja Duńczyków ("Avenue of the Danes"), which is commemorated by a memorial stone. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 some 18,000 French POWs were brought to the town, however, 5,000 were soon relocated elsewhere.[6] According to the Prussian census of 1910, the city of Neisse had a population of 25,938, of whom around 95% spoke German, 4% spoke Polish and 1% were bilingual.[7][failed verification]

World wars and interbellum

[edit]During World War I and the post-war Polish Silesian Uprisings, a prisoner-of-war camp was located in the town.[2] The WWI POW camp held Russian, British, French and Romanian officers.[6] Charles de Gaulle, future leader of French Resistance against German occupation in World War II and later president of France, was imprisoned there in 1916, and after an unsuccessful escape attempt he was deported to a POW camp in Szczuczyn.[8] Russian POWs, still detained by the Germans after the end of the war, raised a mutiny in December 1918, to which the Germans responded with fire.[5] Two or three Russians and a German guard were killed, 11 Russians were wounded.[5] After World War I, Neisse became part of the new Province of Upper Silesia within Weimar Germany. Polish insurgents of the Silesian Uprisings were imprisoned in the camp before being deported to other camps.[9]

During World War II the Germans established a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, three forced-labour camps,[3] and several working parties of the Stalag VIII-B/344 prisoner-of-war camp at Łambinowice.[10] The city's German population was mostly evacuated before the advancing Eastern Front, with some 2,000 mostly ill people and elders remaining.[11] The city was conquered by the Red Army on 24 March 1945.[11] Soviet troops then raped dozens of women, including nuns, teenage girls and elderly women, murdered 27 nuns and six monks, and set fire to an old people's home with the elderly locked inside.[11]

The town was placed preliminarily under Polish administration in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement and renamed to the historic Polish Nysa. The remaining German population of Nysa was expelled. Expulsions started in mid-June 1945, carried out by the Soviet-organized Polish militia who surrounded settlements, entered homes, and asked their inhabitants to leave their home with them.[12] In the following years, new Polish settlers, some whom were themselves expelled or resettled from what is now western Ukraine (see: Kresy), made Nysa their new home.

After the war, Polish troops were stationed in Nysa until 2001, when they were relocated to Kłodzko.[2]

Nysa's monuments

[edit]

As a result of destruction during World War II, in particular the heavy fighting of the Vistula–Oder Offensive and the Lower Silesian offensive of early 1945, during which the Red Army pushed the German Army Group A out of southwest Poland and the adjacent German Lower Silesia, the historic aspect of the town has only partially been preserved due to wartime destruction. After Polish takeover of the town, hundreds of historic burgher houses deemed reconstructable were struck down in line with the Communist's ideological goals of degermanization and struggle against the bourgeoisie as well as to provide material for the re-building of Warsaw.[13] The most important monuments have been rebuilt.

Economy

[edit]

Until recently, Nysa was a major industrial centre in the Opole Voivodeship. The town was home to metal works, machinery production, agricultural produce and construction materials. The year 2002 saw the closure of the ZSD company. The company constructed delivery vehicles, namely the ZSD Nysa, FSO Polonez and, until recently, the Citroën C15 and Berlingo. Currently, the factory remains closed.

Recently, the Wałbrzych Special Economic Zone[14] is located by Dubois Street (ul. Dubois) and Karpacka Street (ul. Karpacka), largely revolving around agricultural goods and produce, as well as metal works.[15]

Sports

[edit]- Stal Nysa SA – men's volleyball team playing in Polish Volleyball League (Polska Liga Siatkówki, PLS), new in 2020 season

- KŻ Nysa – sailing club with seat on Nysa's lake

- AZS PWSZ Nysa – students club of AZS

- Polonia Nysa – football club

- Podzamcze Nysa – football club

- AZS Basket Nysa – basketball club

- NTSK Nysa – women's volleyball club

- Fort Nysa – rugby and Australian rules football club

- NTG Nysa – gymnastics club

Notable people

[edit]

- Konrad Emil Bloch (1912–2000), German-American biochemist, Nobel Prize winner

- Emanuel Sperner (1905–1980), German mathematician

- Marcin Bors (born 1978), Polish record producer

- Hans-Joachim Caesar, Reichsbank director, German bank comptroller in occupied France, 1940–44

- Emanuel Oscar Menahem Deutsch (1829–1873), scholar on the Middle East

- Paweł Franczak (born 1991), Polish cyclist

- Rudolf Fränkel (1901–1974), architect

- Sigismund Freyer (1881–1944), German horse rider

- Piotr Gacek (born 1978), Polish volleyball player

- Bernhard Grzimek (1909–1987), zoologist and conservationist

- Wilhelm Hasse (1894–1945), Wehrmacht general

- Martin Helwig (1516–1574), cartographer

- Max Herrmann-Neisse (1886–1941) German poet

- Max Hodann (1894–1946), German physician

- Carl Hoffmann (1885–1947), German cinematographer and film director

- Jakub Jarosz (born 1987), Polish volleyball player

- Valentin Krautwald (1465–1545), German religious reformer

- Bartosz Kurek (born 1988), Polish volleyball player

- Adam Kurek (born 1968), Polish volleyball player

- Edmund Lesser (1852–1918), German dermatologist

- Maria Merkert (1817–1872), founder of the Congregation of Saint Elizabeth

- Kurt von Morgen (1858–1928), Prussian explorer and officer

- Hans Guido Mutke (1921–2004), fighter pilot

- Emin Pasha (Eduard Schnitzer) (1840–1892), physician and Ottoman governor of Equatoria

- Karl-Georg Saebisch (1903–1984), German actor

- Friedrich von Sallet (1812–1843), German satirical writer

- Solomon Schindler (1842–1915), rabbi

- Franz Skutsch (1865–1912), German classical philologist and linguist

- Ryszard Wasko (born 1947), Polish artist* Max Ernst Wichura (1817–1866), German lawyer and botanist

- Arnold von Winckler (1856–1945), Prussian general

- Roman Wójcicki (born 1958), Polish footballer

- Krzysztof Wójcik (born 1960), Polish volleyball player

- Angela Zigahl (1855–1955), German teacher and politician

- Ewa Wiśnierska (born 1971), member of the German paraglider team

Other residents

[edit]- Isidor Barndt

- Nicolaus Copernicus

- Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff

- Karl Rudolph Friedenthal

- Eduard von Grützner

- Franz Ludwig von Pfalz-Neuburg

- Christoph Scheiner

- Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

- Wacker von Wackenfels

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Population. Size and structure and vital statistics in Poland by territorial division in 2019. As of 30th June". stat.gov.pl. Statistics Poland. 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Nyskie kalendarium militarne". Nasza Nysa (in Polish). Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Nysa". Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "Michał (Michał Tomasz Korybut Wiśniowiecki)". Internetowy Polski Słownik Biograficzny (in Polish). Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Stanek 2013, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Stanek 2013, p. 98.

- ^ Belzyt, Leszek (1998). Sprachliche Minderheiten im preussischen Staat: 1815 – 1914 ; die preußische Sprachenstatistik in Bearbeitung und Kommentar. Marburg: Herder-Inst. ISBN 978-3-87969-267-5.

- ^ Stanek 2013, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Stanek 2013, p. 108.

- ^ "Working Parties". Stalag VIIIB 344 Lamsdorf. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Hanich, Andrzej (2012). "Losy ludności na Śląsku Opolskim w czasie działań wojennych i po wejściu Armii Czerwonej w 1945 roku". Studia Śląskie (in Polish). LXXI. Opole: 217–218. ISSN 0039-3355.

- ^ Tragödie Schlesiens 1945&46 in Dokumenten (in German). Christ Unterwegs. 1952–1953. p. 227.

- ^ Marek Zybura (2005). Der Umgang mit dem deutschen Kulturerbe in Schlesien nach 1945. Senfkorn-Verlag Theisen. pp. 18–19.

- ^ "Home – WSSE Invest-Park. Wałbrzyska Specjalna Strefa Ekonomiczna Invest-Park". WSSE Invest-Park. Wałbrzyska Specjalna Strefa Ekonomiczna Invest-Park. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ "Nysa » mapy, nieruchomości, GUS, szkoły, kody pocztowe, wynagrodzenie, bezrobocie, zarobki, edukacja, tabele". www.polskawliczbach.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "NEISSE BUCH DER ERINNERUNG", Dr. Max Warmbrunn & Alfred Jahn, Gedruckt bei Druckhaus Nürnberg GmbH, 1966

External links

[edit]- Jewish Community in Nysa on Virtual Shtetl